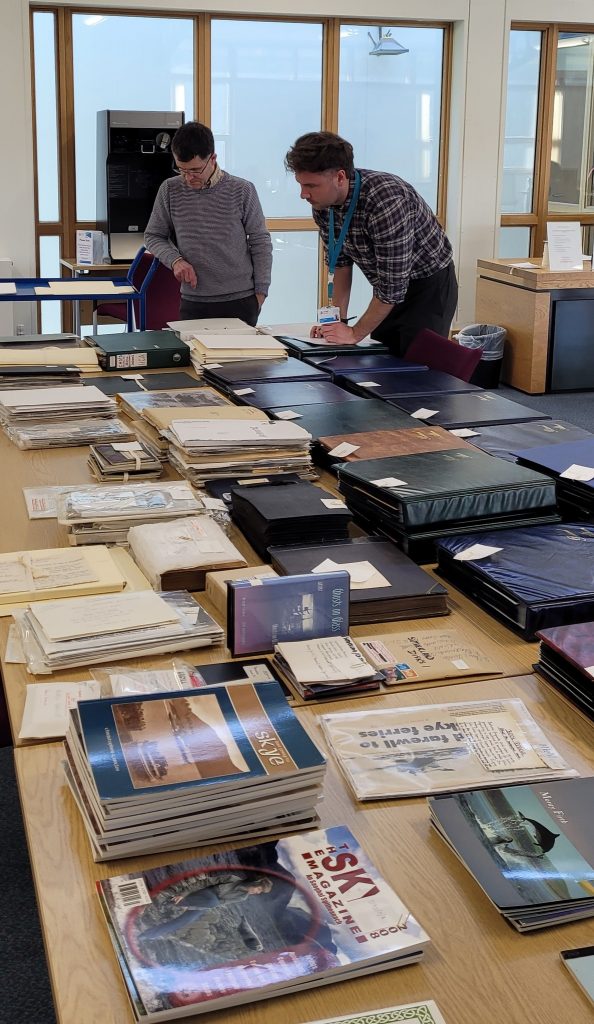

Lorna with Dr Heather Cateau, Dr Henderson Carter and Dr Stephen Mullen

In June 2024, we were proud to take part in ‘Transnational Island Museologies’, a conference held at St Andrews University and attended by over 180 people from 47 nations. As part of the conference programme, our Community Engagement Officer, Lorna, participated in a round table discussion about the impact and ongoing legacy of Eric Williams’ landmark book ‘Capitalism and Slavery’, and the influence of colonialism on archive and recordkeeping practices both in the past and in the present. In addition to taking part in the conference, Lorna wrote an accompanying paper which we’re now delighted to share here. Outlining the process of archiving, from accession to access, it presents some of the challenges faced by archivists and some of the things we consider when taking in, cataloguing, and sharing archival material.

‘Enabling historiography: the responsibility of the archivist as conduit’

Lorna Steele-McGinn, Highland Archive Service, High Life Highland

Abstract

Researchers, historians, writers, and academics all use archives as raw material. A starting point from which to shape books, articles, and teaching material. But in some respects, this is an end point for an archive collection which has already been on a journey – a process of creation, collection, appraisal, cataloguing, description, and access considerations. This paper seeks to shed light on the ways in which the entire archival process can both expose the past and shape the future and seeks to highlight the many considerations faced by the archivists of today in getting a collection to the point of use.

Introduction

The question of who writes history, and for whom, is one which has arisen for centuries. All historiography carries with it the conscious or unconscious biases, attitudes, and prejudices not only of its author but of its era and context. Raw material in the form of archives is shaped and used to support the theory, belief, or ideological aim of the writer.

But who has provided that raw material? Who has chosen what records should be kept, where they should be stored, how they should be accessed, and by whom? Is the process of recordkeeping in itself an act of writing history?

Archivists, in both professional and non-professional settings, carry that responsibility, and with it the risk of sustaining or perpetuating inequalities and attitudes through their decision-making at every stage of the process. It is a responsibility which currently weighs heavily on the profession. Archivists have traditionally been employees of the state or other institutions, their wages paid by those whose decision-making in the past has created some of the very inequalities they now strive to address. Archival theory owes much to the work of Sir Charles Hilary Jenkinson whose Manual of Archive Administration has shaped archival principles since its publication in 1922, but who was employed by a government witnessing, and resisting, the end of the British Empire. His vision of archivists as neutral custodians was therefore idealistic but his dominance in the field has meant that others who have come with different perspectives, such as Caribbean theorist Arthur Schomburg, have been overshadowed (Ishmael, 2018).

This paper will seek to examine the ways in which the entire archival process can play a part in both exposing the past and shaping the future, from the collection of records, through appraisal and cataloguing to enabling access and active dissemination.

Collecting

Archives cannot tell a complete story. Records have been lost over time, some have been actively destroyed to support or obscure a narrative, some never existed because those who could have created them had no opportunity to do so. Archives cannot be neutral because some voices, some experiences, some demographics, will always dominate. Even the most complete collection will not tell a full story.

The question of where archives are, and where they should be, is part of this narrative. Many collections exist in official institutions as a result of historic power imbalances – the coloniser’s evidence of ‘ownership’. Archives displaced from their country of creation are common, with questions arising about legitimate ownership and the responsibilities that come with custodianship. Agostinho (2019) illustrates this in relation to archives from the Danish West Indies/US Virgin Islands.

Archives often strive to increase and diversify the voices represented in their collections but challenges, both practical and emotional, are faced by those handing over archive material to institutions. To what extent does control of the records mean control of the subject of the records? (Bastian, 2002, as cited in Agostinho, 2019 p.149). How can those relinquishing that control trust the organisations to whom they are giving it? And with archives often resource-thin, how can they offer confidence that collections will be made accessible before years have passed?

The archival accession process has some elements of reassurance. Ownership of archives does not need to be relinquished – collections can be deposited with an archive rather than gifted – ensuring that some control of the content is retained while the physical records are protected. Postcustodial theory suggests that collections do not even need to be deposited in an archive. Owners and creators can maintain the records themselves with the practical and professional assistance of archivists, enabling the documents to be catalogued and made accessible more quickly but potentially risking the loss of some professional standards and protection. Recognising the power, and therefore the responsibility, that comes with officialdom is the first step towards encouraging confidence in the archival process.

Appraisal

Collections which make their way into an archive face an appraisal process, where records deemed to be of long-term value are retained and those classified as having no further value are destroyed or offered back to the depositor. This process, although governed by the collecting policies and remits of individual organisations is nevertheless, unavoidably, subjective. The limit to what a document can tell you, is only limited by the questions you ask of it, and it is impossible to predict the questions of the future. Who decides the definition of ‘no further value’?

Trust has been eroded in the ‘neutrality’ of recordkeepers following the destruction of documents such as the Windrush landing cards but the reality is that archives cannot keep everything, despite Jenkinson’s belief to the contrary.

It is vital that there is transparency at this stage of the process, with evidence of decisions taken. In the spirit of ‘who polices the police’ it is also important to ask ‘where are the records of the record keepers’?

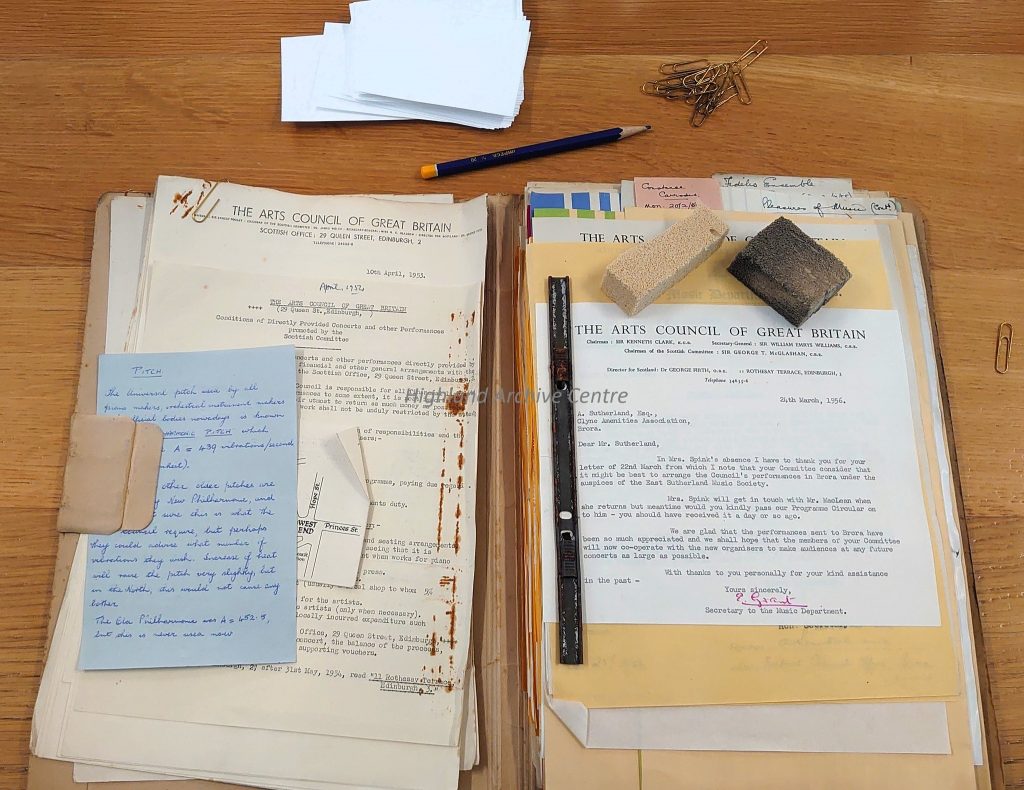

Cataloguing

It is perhaps in the area of intellectual control that the archivist wields most power and must be most hyperaware. The way a collection is structured, its provenance determined and detailed, the way in which it is catalogued, and the words used to describe its contents, will all determine the way in which future users will access it, and these decisions are frequently made by those with no direct connection to, or deep understanding of, the subject matter. Given the range of material many archives handle, this is perhaps no surprise.

In working towards culturally sensitive management of collections it becomes imperative to consult with, and listen to, representatives of those who do have a connection with the subject matter. Not only does this reduce (although not eliminate) the risk of bias or unintentional ignorance, but it goes some way to shifting the power balance from the archivist to the archived.

When cataloguing archives related to Britain’s colonial past the issues are manifold. Outdated and offensive terminology proliferates but the best way in which to tackle this remains debated. Archivists have both a duty to preserve the integrity of the record but also to assist and support the users of that record. There is, of course, no question of altering original documents but how should those documents be described in finding aids in a way that neither whitewashes the truth of their content nor offends or distresses those looking through finding aids. These decisions have access ramifications as will be discussed below.

Multiple solutions to the descriptive practices question have been proposed, from asking relevant user groups to create tags for a collection, to incorporating both the original wording and an alternate wording in a description, but there is no simple solution. Who should decide which words or phrases are offensive or are likely to be offensive in the future? What should be done with words which are not intrinsically offensive i.e. ‘owner’ but which are altered by their context i.e. ‘slave owner’. Is it enough to place a content warning at the beginning of collections to advise that material contains outdated wording or is there a further obligation?

The extensive work of Carissa Chew[1] and of Alicia Chilcott[2], among others, is evidence of the profession’s desire to face these issues but implementing solutions is time-consuming and would frequently have to be done retrospectively to collections which have been catalogued for decades.

Beyond the thorny issue of terminology in collections which deal explicitly with colonialism, there is the question of provenance. Should archivists actively dig into the provenance of record creators to highlight their connections to colonialism even when those connections aren’t immediately obvious within the collection, and if so, should that ideally be retrospectively applied to all collections held by an institution? Walch (1994, p.2), with other members of the Working Group on Standards for Archival Description, defines archival description as “the process of capturing, collating, analysing, and organising any information that serves to identify, manage, locate, and interpret the holdings of archival institutions and explain the contexts and records systems from which those holdings were selected”, but this presents numerous challenges as witnessed by the pilot project undertaken to uncover ‘slave-ownership’ within St Andrews University Special Collections (Buncombe & Prest, 2022).[3]

Many collections were, of course, catalogued prior to the invention of the internet with its ability to pull up information in seconds and most archives will simply have neither time nor resource to accomplish this retrospectively, but without doing so, the archive continues to tell half a story.

Access

It is generally acknowledged today that providing access is part of custodial responsibility, and perhaps particularly a responsibility to those represented within a collection – the voiceless part of the provenance. But the word ‘access’, while suggesting openness, is loaded. It reinforces where power lies and emphasises the fact that the organisation which holds a collection has the ability to grant or deny that access.

While the provision of access is increasingly recognized as a significant, even primary component of the custodial obligation, access remains a contested notion and practice within debates on decolonizing archives and colonial heritage. If there is a consensus that documented communities are entitled to facilitated access to the records containing their histories, that access is often implicated in and conditioned by power differentials that complicate, and may undermine, decolonial aspirations. (Agostinho, 2019, p.151)

In addition, the word ‘access’ has multiple meanings which all need to be considered, from physical access to the building which houses a collection, to the ability to read and understand it.

In order to access archive material related to Britain’s colonial past that material needs to be catalogued in such a way that it is discoverable. Here the issue of terminology is once again paramount – leave the original wording as the description and you risk people not finding it. Change the wording and you risk rendering the description obsolete over time.

Another access challenge to archivists is that of impact on diverse users. Some, but not all, of those interacting with an archive, or with the finding aid or catalogue, will have a personal connection to the subject matter. They may be using it for one reason but at the same time be feeling a profound personal impact. Users’ experiences with any given document is not universal and the archivist needs to be aware of the potential for trauma or distress.

Interpretation and engagement

Once a collection is catalogued and made accessible, at least in the traditional sense, what can or should archivists do with it? Is it the archivist’s role to simply act as a passive guardian of the record or, assuming Jenkinson’s vision of neutrality unachievable, is there a responsibility to actively disseminate the information within archive collections?

If, as would seem likely, neutrality is impossible due to inbuilt systemic processes and structures both historic and current, how can we be sure of the right, culturally sensitive, way to interpret archive material and engage diverse audiences? We return to the question which opened this paper – who is writing history and for whom? As a majority white profession in the UK, do we have the right to tell this story? Do we have the right not to?

Looking ahead

The responsibility of acting as conduit to the raw material of history is currently a matter of great, and passionate, discussion within the archive profession. The issues are manifold and systemic – it is not as simple as flagging offensive words. It is a challenge to diversify the profession, (part of the strategic vision of the Archives and Records Association)[4], to re-examine the nature of custodial responsibility, to embed inclusivity in our professional standards through updating the Archives Accreditation process[5], and to engage openly and meaningfully with a range of audiences. There are divisions within the sector about how to achieve these ends, and polarised opinions about what is needed.

The Archives and Records Association, the leading professional body for the archive sector in the UK and Ireland, is a signatory to the Heritage Alliance’s Anti-Racism statement which acknowledges that “our nation’s history and heritage is an invaluable tool in the fight against racism and discrimination.” ARA has developed a Diversity and Inclusion Allies Group to advise the sector on best practice, but for long-term change, these discussions will need to be embedded into the education system that shapes the archive profession. If archive and records management courses do not address the issues raised in this paper, how will the next generations of archivists be equipped to engage with them meaningfully?

As the conduits through which many access history, archivists have both the power and responsibility to tackle these questions, but need to be educated, resourced, and equipped to do so.

References

Agostinho, D. (2019). Archival encounters: rethinking access and care in digital colonial archives. Archival Science, 19, 141-165. DOI: 10.1007/s10502-019-09312-0

Bastian J.A. (2002). Taking custody, giving access. A postcustodial role for a new century. Archivaria, 53,76–93

Buncombe, M. & Prest, J. (2022). Making ‘slave ownership’ visible in the archival catalogue: findings from a pilot project. Archives and Records, 42(3), 228-247. DOI: 10.1080/23257962.2021.1985443

Ishmael, H.J.M. (2018). Reclaiming history: Arthur Schomburg. Archives and Manuscripts, 46(3), 269-288. DOI: 10.1080/01576895.2018.1559741

The Heritage Alliance (n.d.). Anti-Racism Statement. https://www.theheritagealliance.org.uk/anti-racism-statement/

Walch, V.I. (1994). Introduction. Walch V.I. (Ed.), Standards for archival description. A handbook. (p.2). Society of American Archivists.

[1] More information about the work of Carissa Chew can be found at https://carissachew.com/ and https://culturalheritageterminology.co.uk/

[2] Alicia Chilcott’s work on promoting inclusive practice within archives includes developing a series of protocols for describing racially offensive language.

[3] This project sought to cross-reference the St Andrews University Special Collections catalogues against the Legacies of British Slave-ownership database (https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/) and met with various challenges in both the process and the practicality.

[4] Further information about the strategic priorities of the ARA can be found at https://www.archives.org.uk/news/ara-publishes-its-equity-diversity-and-inclusion-strategic-direction-report

[5] Further information about the new focus areas for Archives Accreditation can be seen at (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/archives-sector/archive-service-accreditation/archive-service-accreditation-10-year-review/).