As well as maximising their profits from turning the land over to sheep, landlords were regularly increasing the amount of rent they charged the crofters. From the mid-18th century tenants on the Macdonald estates paid a proportion of their rent in kind – usually butter, cheese and corn.

Most crofters living in Braes were in rent arrears, and this arose partly because the Macdonald estate administration would regularly increase rents during periods of good economic activity such as the kelp boom and the rising cattle trade. This enabled landowners to cream off some of the money they reckoned was going to the crofters. Rents were usually increased just before a downturn in the economy, and although they usually put the rents down again, there was enough of a time lag for arrears to build up.

Additionally, there had been two major failures of the potato crop – in the late 1830s and during the better-known famine period from the early 1840s, rents were not lowered. The estate carried forward the crofters’ arrears each year so most of them were in permanent debt to Lord Macdonald and many faced eviction.

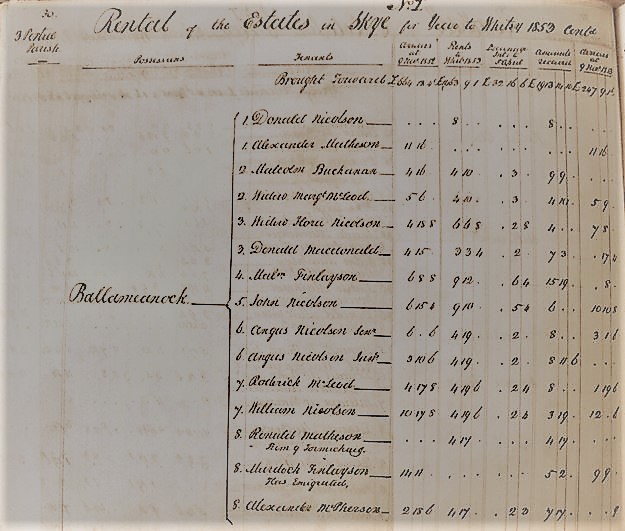

Balmeanach

Estate rent books from 1853 show how bad the situation for the crofters was. Angus Nicolson Jnr of croft No 6, managed to pay everything off, while Malcolm Finlayson at No 4 managed to pay off all but 8 pence. In October 1852 Murdo Finlayson, tenant of half of croft 8, emigrated to Australia with his wife Catherine Buchanan and son Malcolm. They sailed on the ship Priscilla with 296 passengers, 36 of whom were from St Kilda, on the voyage to Geelong, in Victoria as part of the Highlands and Islands Emigration Society scheme of assisted passages to Australia.

The Scheme contributed 1/3 of the passage costs, the landlord (ie Lord Macdonald) contributed another third and the emigrant family contributed the rest. When he left, Murdo owed £14.11s rent, he managed to pay £5.2s of this debt in 1853. He remained liable for the debt although he had emigrated and, as he owed Lord Macdonald money, his name remained in the rent book.

In 1852/53 Ronald Matheson took over Croft No 8. He was among those who had been cleared from their homes in the township of Tomichaig in the previous year. Lord Macdonald had cleared Tomichaig township to incorporate it into deer forest and unusually for a cleared village the tenants were paid for their houses. Ronald was paid £3.0s.6d for his house, and this might be why he had enough money to pay the full rent in 1852/53.

Finding another croft somewhere else for a tenant from a cleared township was quite common. All the Tomichaig tenants were accommodated in this way, sometimes they took over the croft of someone who was leaving, voluntarily or not. Sometimes it meant that the croft was split between the new tenant and the original tenant, thus reducing the holding of the original tenant.

“The pitiable condition of the people – the hovels in which they are housed, the sterile soil from which, with much toil, they scrape a scanty sustenance – combined with the gradual limitation of privileges…which they formerly enjoyed, have reduced the crofters almost to despair”

From a report from the Glasgow Herald, April 22nd, 1882, on the sorry state of Kilmuir crofters.

Godfrey William Wentworth Bosville-Macdonald (1832-1863), 4th Lord Macdonald was severely in debt, and began to sell large parts of his Highland estates. In 1855 he sold Kilmuir estate to Captain William Fraser who was well known for his anti-crofter views. Captain Fraser quickly raised the crofters rents not long after the initial purchase, and raised them again in the 1870s.

By the 1870s, there came a stepping-up of agitation and anti-landlord activities amongst the crofters, inspired by similar land wars in Ireland. The crofters of Skye began to form organised groups and started to challenge the authority of their landlords.

Valtos

The first example of direct action by Skye crofters occurred in the township of Valtos on the Kilmuir estate.

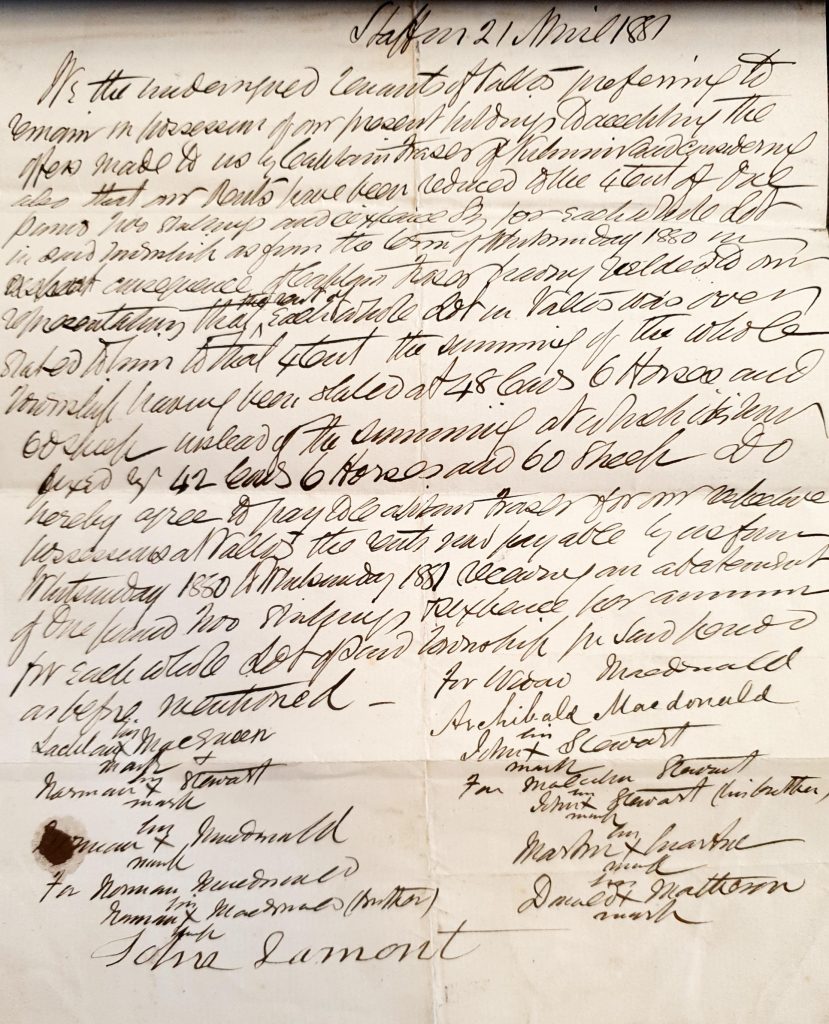

In 1881 the Valtos’ crofters gave notice to their landlord Captain Fraser that they would no longer pay his high rents and they defiantly refused to pay the increases. Fraser’s threats of evictions were simply ignored by the crofters of Valtos and he backed down before the threat of his tenants’ rent-strike.

John Murdoch, publisher of The Highlander newspaper, was quick to condemn Captain Fraser and, as a sign of the growing interest and publicity for the cause, the Irish Nationalist and Land League Leader Charles Stewart Parnell addressed a mass meeting in Glasgow, condemning landlords like Fraser for their actions.

As Alexander MacDonald, Lord Macdonald’s factor later reported, “that was the beginning of it” (Mightier than a Lord, I. F. Grigor, 1985). In the same year, the crofters of Glendale followed the Kilmuir crofter’s example, combining rent-strike tactics with direct land occupation.

A transcript of the Valtos petition shown above can be found here.

Glendale

Glendale had been deliberately overcrowded by landlords since the 1840s, with the people having to make what living they could from their little patches of land and from the sea. On the 4th of January 1882, the estate management displayed a notice in the post office, stating that, whereas the local people had been in the habit of trespassing on the land of Glendale, Lorgill, Ramasaig and Waterstein while searching for and carrying away drift timber…

“Notice is hereby given that the shepherd and any persons found hereafter on any of the said lands, as also anyone carry away timber from the shore by boats or otherwise, that they be dealt with according to law.”

The Glendale people met at their church on 7th February 1882 ‘for the purpose of stating our respective grievances publicly, in order to communicate the same to our superiors.’

At the meeting it was decided that each township would petition their landlords for redress of their grievances. The petitions were rejected and their response was a rent strike and they drove their hungry cattle onto the farm of Waterstein. The estate management turned to the Court of Session and requested an order requiring the crofters to remove their stock from the private grass. The order was ignored by the crofters.