410 million years ago, the rocks forming the summit of Ben Nevis only survived erosion because it collapsed into a chamber of molten granite magma.

410 million years ago, the rocks forming the summit of Ben Nevis only survived erosion because it collapsed into a chamber of molten granite magma.

600 meters from crossing the stile at Achintee, there is a small crop of metamorphic rock, called hornfels, on the East side of the path. Originally an impure limestone affected by the heat from the Ben changed it to a pale green and white banded rock.

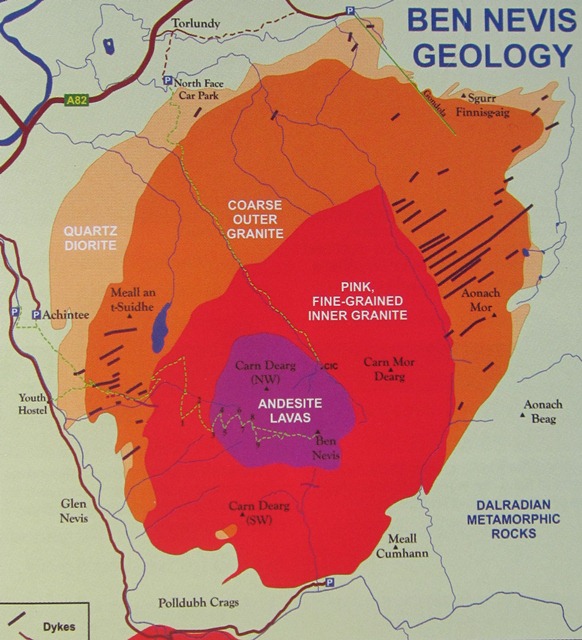

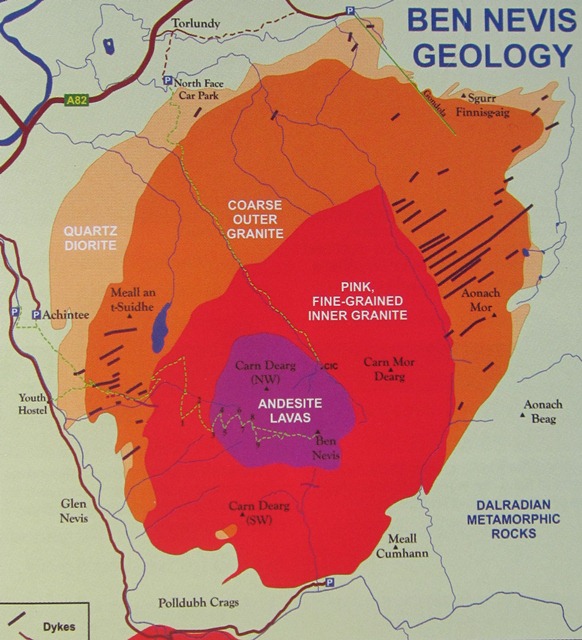

Not long after hornfels, the path turns into quartz-diorite. This rock is very similar to granite but is grey in colour.

Where the path from the youth hostel meets the main path, you will come across a coarse-grained granite known as Nevis Outer Granite. As you get past the first two ‘zigzags’ you can see several dykes cutting through the granite.

Shortly before the lochan (Meall and t-suidhe), a much rendered granite called Ben Nevis Inner Granite is seen where the path turns Southwards across the Red Burn and the first three major zigzags on the Western flank of the mountain.

At the top of the third zigzag, you will come across a dark grey-coloured rock. This is all volcanic rock, mainly andesite lavas, and is the formation of the top section of the mountain and represents a 2 km-across cylindrical block that sank into granite whilst still molten.

The summit of Ben Nevis was once over 600m (2000ft) higher than today before it collapsed into the chamber of molten granite and created a massive crater on the surface called Caldera. Huge amounts of frothy magma and hot ash caused erosion of a vast amount of rock.

So, when standing enjoying the summit of Ben Nevis you are actually directly beneath the centre of the former Caldera. A book about the unique geology of Ben Nevis can be purchased from the Lochaber Geopark Website.

410 million years ago, the rocks forming the summit of Ben Nevis only survived erosion because it collapsed into a chamber of molten granite magma.

410 million years ago, the rocks forming the summit of Ben Nevis only survived erosion because it collapsed into a chamber of molten granite magma.