As Rachael mentioned in the last blog, we recently travelled over to Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis, to courier some objects from the Highland Folk Museum to an exhibition entitled Cuimhne/Memory. This exhibition is an exploration of objects, creativity and memory, and is just one outcome of the Arora project. This is a project based in the Western Isles, helping people living with dementia:

“Arora is an An Lanntair initiated project, founded on the core values of community care, creative spirit and shared culture. It is born of a community, shaped and defined by its history, language and unique culture. We proactively promote the Gaelic language and explore the role bilingualism has in relation to dementia. Through Arora, people living with dementia have been involved in exhibitions, creative workshops, art sessions, cultural hand memory (including net mending and spinning workshops), short film screenings, music, personal story recordings, traditional cèilidhs, and creative reminiscence. Together, Arora is lighting the way and becoming a beacon for real change.”(1)

Cuimbne/Memory exhibition, An Lanntair, Stornoway

Objects from the Highland Folk Museum on display at An Lanntair (From top left, running clockwise – mudag, ciosan, marram grass brush, puffin snare, horsehair line and quill, sample of horsehair rope)

Objects and making are intrinsically linked to memory – to “muscle memory” and “embodied memories”, and to memories of a particular place and time. The objects that we took across to Lewis originate from the Hebrides – a mudag (wool basket) from Lochmaddy, North Uist; a ciosan (grain basket) from South Uist; a marram grass brush from Bernera; a horsehair rope of the type used on St Kilda; thin horsehair line and quills from Iona; and possibly the last remaining example of a horsehair puffin snare from St Kilda, as discussed by Rachael in the previous post. Many years ago, these objects all would have been common items, made by islanders from the materials they found around them, and then used in their everyday lives.

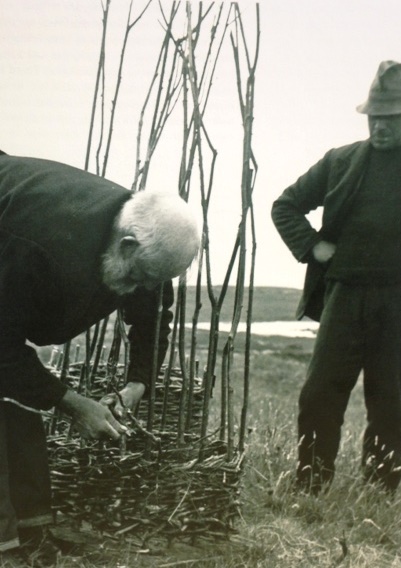

A traditional creel being made at Garrynamonie, South Uist, in 1947.

Image credit: Werner Kissling/School of Scottish Studies, in Milliken, W, Flora Celtica (2)

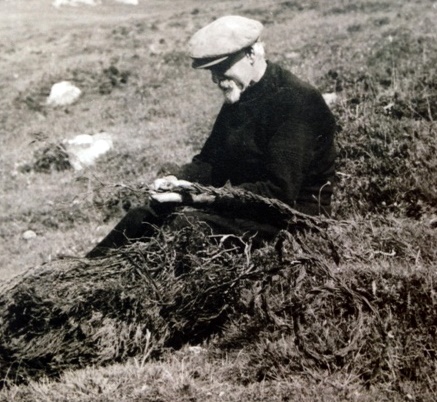

Making heather rope at Lochboisdale, South Uist, 1947

Image credit: Werner Kissling/School of Scottish Studies, in Milliken, W, Flora Celtica (2)

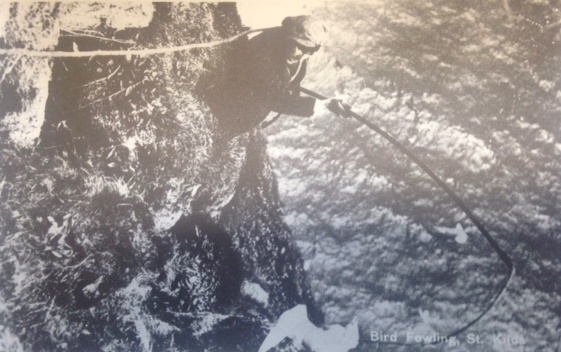

The snare, as sad as it is for the puffins, was literally a lifeline for the islanders, whose very survival relied on catching the seabirds. The sample of horsehair rope that is on display in the exhibition was the type used to lower men off the edge of sheer cliffs, so they could dangle precariously hundreds of meters above the crashing swell of the sea, and catch the famous Hebridean seabird, the fulmar. Along with the puffin, this was another species that supported the human population on St Kilda, and every part of the bird was used to sustain the community through the harsh winter.

Fowling rope from St Kilda in the Highland Folk Museum collection, photographed by I.F. Grant in 1940s. Image credit: Highland Folk Museum

As can be said for so many of the objects we have here at the Folk Museum, the objects now over in Stornoway are connected to making, to hands, to people, to communities, to life and to death. With that comes the connection to memory.

The memory of making forms a part of all hand crafted objects; the intrinsic skill carried out a thousand or more times, where the brain engages with the hands on a deep rooted level, and where little conscious thought is required. Making a rope takes hundreds of meters of material, twined together through the repetition of a task, to make a length of rope that you’d risk your life on, or your father’s, brother’s or son’s life. It must be well made, and indeed the St Kildan ropes were treated as heirlooms, passed down the generations and tested each year to check that they were still strong enough to take the strain.

Fowling for birds using a rope and fowling rod, St Kilda.

Image credit: Last Greetings from St Kilda, Bob Charnley (3)

There’s also the memory connected to using objects. For example the mudags, or wool baskets, were used to hold raw fleece which was then spun into yarn, which could then knitted with or woven into lengths of material. In the Hebrides, the fleece was famously turned into Harris tweed; an internationally renowned craft which supports the livelihood of many islanders, still to this day. One small seemingly insignificant object, the mudag, can spark memories of a whole way of living and working.

This photo is of the “Inverness-shire cottage” in the 1940s, from when the Highland Folk Museum was based in Kingussie. Mrs Grant (no relation to Isabel Grant) was spinning yarn on a wheel, a mudag to the right of her. Joan Grant was “tramping blankets”. Photo credit: Highland Folk Museum

The Arora project makes use of the power of reminiscence by taking “memory boxes” out to people living with dementia, in the aim of triggering memories of their earlier life. There are many projects like these all over the country, and as we’re an aging population, this kind of work is only going to become more important. Memories of home and earlier years, family, upbringing and work all help to keep brains active and engaged, as well as providing comfort and happiness to those living with this condition. If the elderly can be helped to feel less lonely and more connected, they’re more likely to remain in their own homes for longer, which has numerous benefits to themselves, family and wider society. Organisations such as DEEP (the Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project) have lots of useful information about projects like this, http://dementiavoices.org.uk/

Memory box about life on Harris, used by the An Lanntair Arora project

Another concept relating to memories and objects is that of traditional skills. Some of the specific ways of making objects have been lost over time for various reasons, but these lost crafts can be revived by skilled makers. There were some practical workshop sessions that took place during the Cuimhne/Memory exhibition and seminar. Dawn Susan, a well renowned basket maker and member of the Woven Communities project (https://wovencommunities.org/ ), used the Highland Folk Museum’s mudag as the inspiration for a workshop. This kind of basket isn’t being made in large quantities anymore, and so the finer details of how they were traditionally made have been lost. Dawn can closely study a basket such as this though and un-tap the secrets of how it was made. She conducts a basketry autopsy, if you will. For example, she could tell from the exaggerated twist of some of the willow strands where the weaving of the basket would have been started and finished. You need an expert’s eye to unlock those secrets!

Close up of mudag KIGHF.QP.0075. Note the twisted strands in the centre,

looped around the bottom of the opening

Dawn Susan and Stephanie Bunn doing some basket weaving in the gallery, inspired by the objects.

Another maker, Caroline Dear, was running rope-making workshops based on the horsehair puffin snare. She taught us how to make rope using a variety of different materials, such as purple oat straw, heather, reeds and moss. We made lengths of rope and added them into a woven panel.

Caroline showing a participant how to make rope with different materials.

Some rope I made – L-R, purple oat straw, moss, reed

She had also made a large version of the puffin snare, and asked participants to think about rope, and about any memories we might have connected to rope – making it, using it – then to write these memories down and tie them onto the rope snare. I was reminded of my old neighbour, who had in younger years been a gaucho in Argentina – he’d entertain us as children in Yorkshire by putting on lasso-ing demos in the garden, and he made the best swings from old rope and tyres!

Objects are often seen as “dead” objects once they enter a museum. They aren’t dead, they’ve just entered retirement and are no longer in active use. But they can then be used to teach and inspire a new generation about their secrets. Seeing and participating in the making workshops that were going on in the gallery space, with the HFM objects acting as inspiration, was just wonderful. They are anything but dead objects – they are forming the basis of new knowledge, of experts learning new things they hadn’t realised, and of novices learning brand new skills. They hold old memories and they can also create new ones.

Helen

- An Lanntair. Award winning Arora project launches new website. http://lanntair.com/8693/ Accessed 27/04/2018. See also dfclanntair: Dementia Friendly Communities project at An Lanntair, Stornoway blog

- Milliken, W. and Bridgewater, S. (2006) Flora Celtica. Edinburgh: Birlinn. Pg. 107 and pg. 191

- Charney, B. (1989) Last Greetings from St Kilda. Glasgow: Stenlake & McCourt. Pg 26

Previous blog post – Horsehair and snare