In 2019, the making of shinty sticks, or camans, was designated as a critically endangered craft by the Heritage Crafts Association. This means that it is currently viable due to one or two main producers, but if for some reason they stopped making, the future of the craft would be under serious threat.

As I mentioned in my last blog post, the sport of shinty is not just surviving, it is thriving. There are numerous established and newly formed teams across the Highlands and the Lowlands, in cities, towns and villages, and in schools and universities. Every player needs (at least) one caman, so it might be hard to see how supplying this substantial market with its essential equipment is classed as at risk. A caman is not just a stick though, it takes considerable skill and time to make a good one. Camans have developed enormously from the early years of the game where each player made their own from whatever wood they could find locally, to the laminated modern sticks of today suited to the regulated and sophisticated game that shinty has become.

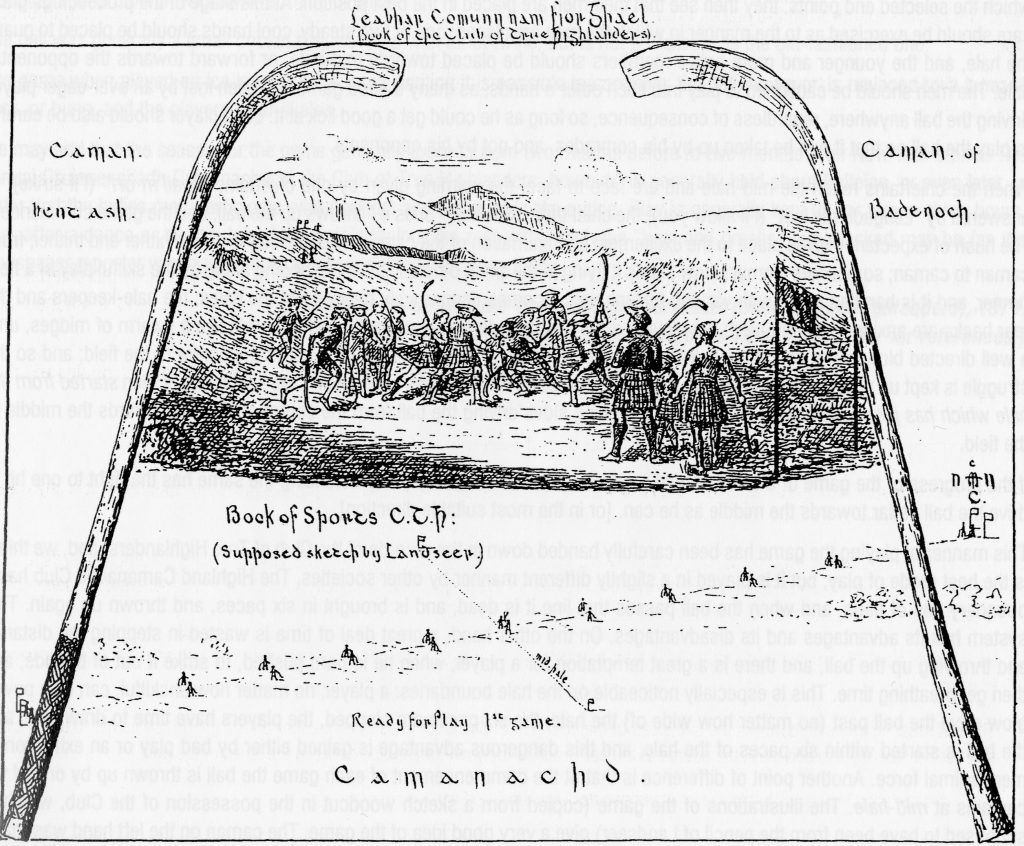

An illustration of a Badenoch caman and an ash caman, from the 1881 publication The Book of the Society of the True Gael (1)

The modern shinty stick

The making of a shinty stick is an art. Each one is hand-made; there is no caman making machine churning them out. There are a small number of caman makers working in Scotland, and one or two in England. Tanera Camans in Inverness are the largest scale producers of camans currently in operation, working full time on making the sticks. Other companies such as Munro Camans (John and Mabel Sloggie) and Kyles Camans (the Blair family) produce sticks as a side or part time operation and along with other individuals have been instrumental in keeping the craft alive and the sport supplied.

A laminated stick made by Tanera Camans. Image credit: Highland Folk Museum

A full length Kyles Caman, and a cut-down Munro Caman, for use by a child. Image credit: Highland Folk Museum

Caman making is often referred to as a labour of love. It’s not usually undertaken as a get-rich-quick scheme. Makers are usually shinty players too, and have an innate understanding of the feel and handle of a stick.

Rather than being made from one piece of wood, the majority of modern shinty sticks are now made from thin strips of wood, usually hickory, laminated together with adhesive. They are pressed together and the stick is then steamed, and when pliable the end is bent into the distinctive hook shape that gives the caman its name – the Gaelic word “cam” means bent or crooked.

When dried and cooled, the laminated stick is pared down into the finished caman shape: the foot, or bas, is triangular in shape with two flat sides (unlike in hockey, the ball can be played on either side of the stick); the shaft and handle, or cas, is planed down until smooth and then the whole stick is varnished. Often the stick will be left long, and cut down to suit the height of the player, before a taped grip is added to the handle. Historically the grip was made from a leather strip.

Mabel and John Sloggie, of Munro Camans, photographed by Donald Mackay in 1992 in the process of making laminated camans. The Sloggies, now in their 80s, are still making sticks. Image credit: Donald Mackay

There are no nails or metal components allowed on a stick, and edges must be rounded off to reduce the possibility of injuring an opponent. To be “legal” on the pitch, the caman must be able to pass through a ring of 2 and a half inch diameter. This sizing rule was brought in in the 1920s, and a referee would have carried such a ring with them to ensure compliance.

Image credit: Highland Folk Museum

At first glance, all sticks may look the same, but there are many subtle variations that affect the whip of the stick and the loft it can achieve with a strike. The angle of the bend, and the weight and thickness of the head dictate how it plays, with defenders’ sticks being heavier with a larger sloped bas, and forwards’ camans being lighter with flatter faces.

Solid wood camans in various stages of completion, showing differences in shape. Unknown makers. Image credit: Highland Folk Museum

Early camans

Going back to the early days of shinty, before it was possible to go out and buy a stick, players would have made their own sticks from wood that was available locally – ash (the favoured wood for camans), birch, beech, rowan, willow, elder and oak are all known to have been used.

Illustration by Robert R McIan of Grant of Glenmoriston “in the attitude of throwing the ball at the commencement of the game of Camanachd or Shinnie”, with a finely made caman, 1845. Image credit: Am Baile/Highland Libraries (2)

This descriptive account of the making of a caman in the Inverness Courier, 1893 sheds some light on the process:

“Of old time, the club was, and to some extent still is, in the more primitive parts of the North, a carefully selected young oak tree, whereof the thickest end has been heated with fire and bent to a curve, which it is made to retain at first by means of thongs. When it is considered to have been long enough bound to retain its shape without the thongs, these are removed, and the club is, in a rude way, ready for use, having a hook at the end of its shaft like the bend of a golf club. Experience has taught however, that nature does not, somehow, very frequently create oaklings of the most convenient forms for camans, and Science meets her half-way by selecting a straight shaft or cas of hazel or ash, and a bas or foot of oak, and joining the two together by splicing, or what in the elegant parlance of the modern Highlander is described as “wupping” with rosined cord. In this wise, plus some trimming with a knife, is a shinty made. It is an elegant weapon, graceful to wield, and of delightful capacity for hacking an opponent’s head, or elevating his knee-cap”. (3)

Birch branch with natural curve. Image credit: Highland Folk Museum

This birch stick in the museum collection is an example of a branch with a natural curve, before it would have been pared down into a playable stick. As it stands it is rather inelegant and unwieldy, although I’m sure in this raw form it would be more than satisfactory for hacking an opponent’s head or elevating his knee-cap.

Insh shinty team in 1892 with their hand-made camans. Image credit: Highland Folk Museum

If no naturally curved branch was forthcoming, bending a length of wood was an option, as described in the Inverness Courier quote above. Steaming a straight “split” of wood and gently curving it into a bas required the bend to be held in place as it dried – either with a length of wire, or by tacking in place two strips of wood, such as in these two examples in the collection. Apparently, the success of the bend was all down to the drying process; if not thoroughly dried, the stick could straighten out if it became wet – a real risk when playing shinty in Scotland.

Caman making in process – one with wire frame, one with wooden frame. Makers and dates unknown. Image credit: Highland Folk Museum

Where wood was in scarce supply, other materials were utilised, for example driftwood was used on Lewis. A 1908 account of shinty on the Hebridean island of Uist states that “As Uist is barren of trees, a tangle [kelp] caman is nearly as common as a wooden one. Another ingenious caman is made of a large piece of canvas bent with both ends caught in the hand. It is very effective”. (4)

This photo shows an unknown group of players, location also unknown. It’s interesting to note the variation in their home-made sticks (and also their smart bowler hats). Their camans might have been made by steaming lengths of wood, or using by naturally curved wood. Image courtesy of Roddie MacLennan (5)

Commercial Camans

At the start of the 20th century, caman making took on a more professional slant thanks to the entrepreneurial spirit of Newtonmore born John Macpherson. John was a shinty player and saw a gap in the market for consistently made, well-balanced, light, good quality sticks. At this time no one was making sticks commercially. He took over his uncle’s shop in Inverness, and John Macpherson Sporting Stores soon became the leading supplier of camans, employing up to 3 caman makers at its height.

John imported hickory from California to timber yards in Portsmouth and Liverpool. In Liverpool, the hickory was cut down into suitable lengths and steam bent, cut into 2 and a half inch squared off “blocks” and seasoned for 8 to 10 months, before being sent up to Inverness where the blocks were worked by John’s caman makers into the finished articles. As a rule, sticks were ordered a dozen at a time, because there were 12 players in a team. The dozen sticks would include a variety of bas angles, suiting the different players across the field.

An early 20th century hickory stick made by John Macpherson, recently donated to the Highland Folk Museum by John’s granddaughter Shelagh Nobel. Image credit: Highland Folk Museum

The outbreak of WWII put paid to shinty stick production due to both lack of materials, and the men to make them. After the war, John Macpherson started producing a spliced stick of hickory head and ash handle, and this became the predominant caman in use until the laminated hickory stick took over.

In 1896, John Macpherson started the tradition of the silver mounted caman being presented to the winning captain of the Camanachd Cup, a tradition that continues to this day. The silver mounted caman has now spread to other competitions and it is not exclusive to the main event in the shinty calendar. (6)

Camanachd Cup winners Kingussie in 1900, with the cup and silver mounted caman (second from left). Image credit: Highland Folk Museum

Nowadays, with the game thriving as it is, and the small number of makers able to cope with current numbers of sticks required annually, it is unlikely that caman making will die out anytime soon. Hopefully the dedicated and talented current makers will train up the makers of the future and continue the legacy of the art of the caman.

These two wonderful films highlight the making process of laminated sticks – the first film features John and Mabel Sloggie of Munro Camans, filmed in the 1980s. The second film from 2018 features interviews with Alan Macpherson of Tanera Camans, and curator Rachel Chisholm talking about the collection here at the Highland Folk Museum.

References:

- Illustration from The Book of the Society of the True Gael, published in MacLennan, Hugh Dan. 1993. Shinty! Nairn: Balnain Books. Pg. 28

- Illustration from James Logan’s 1845 book “The Clans of the Scottish Highlands”. Image credit: Am Baile/Highland Libraries

- Inverness Courier, May 12, 1893. Published in MacLennan, Hugh Dan. 1995. Not an Orchid… Inverness: Kessock Communications. Pg. 215

- Morrison, Alexander. Uist Games, Celtic Review Vol IV, April 1908. Published in MacLennan, Hugh Dan. 1995. Not an Orchid… Inverness: Kessock Communications. Pg. 254

- Image of an unknown group, venue also unknown. Photograph courtesy of Roddy MacLennan, published in MacLennan, Hugh Dan. 1995. Not an Orchid… Inverness: Kessock Communications. Pg. 178

- Information credited to Shelagh Noble in her written account of the John Macpherson & Sons Sporting Stores Inverness which features interviews with her family members including Hamish Macpherson, son of John, who provided an account of the shinty stick making history.

Previous blog post – Blog Post #2 – The Caman; an art and a craft

Next blog post – Blog Post #3 Shinty through the Wars