A Brief Introduction

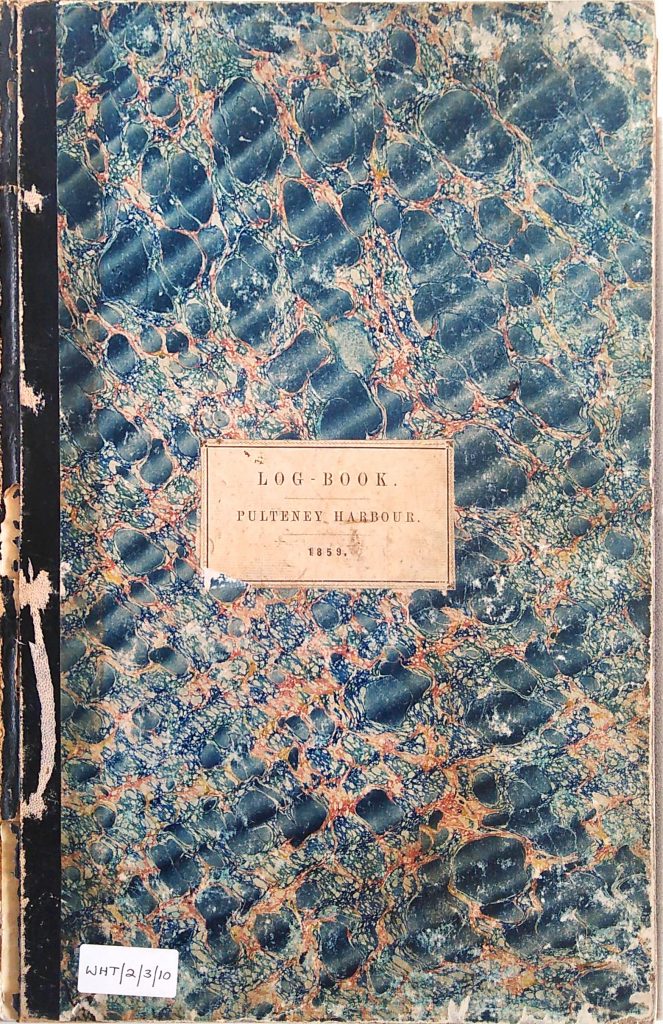

This month we will be showcasing the harbour master log books: an endless source of official declarations, of harbouring and passing ships, of social unrest in the town, of tragic deaths at sea and on land, of unthinkably violent storms and gales. We hold the annual log books for the years 1849-1890 in their entirety. These years saw the peak of the herring fishing, Wick a goliath in the European trade, and its subsequent decline as depleting fish stocks and emigration made their mark. Moreover, this was the time of great seasonal emigration, of highlanders travelling from further afield, inland from Sutherland, over the sea from the Western Isles and Hebrides. They reached Wick and the opportunity to make money to supplement croft cultivation throughout the rest of the year; or after being forcefully banished by landlords to the coasts to start anew. This influx is vivid in the social chemistry described in the log books. Lines of language and culture were often heavily drawn and erupted during the War of the Orange in 1859. The sea itself will stand mountainous within the entries of 1872, along with the failed attempts of the Stevenson’s to tame the mighty waves with their repeatedly destroyed breakwater. Economic and political unrest present themselves through the Trawler Riots of 1885, illustrating the effects of avaricious capitalism on smaller fishing communities and that of the trawlers on the ocean bed itself. Each day has an entry, some extremely short, perhaps simply noting the sighting of a passing steamer or the quality and quantity of herring caught. Others are very lengthy and afford us great, first-hand details of important economic, environmental and political stories from the history of both the harbour and inhabitants of Wick and Pulteneytown.

Authors: The Harbour Masters

A harbour master is an official responsible for enforcing the regulations of a particular harbour or port. As we will be looking at three specific years, spread throughout the nineteenth century, our harbour masters will change. You’ll be able to see this in the idiosyncratic handwriting, the changing personality of the very words and the biased, emotive deliberations held within the entries. Unfortunately, the log books do not disclose their authors. Each annual begins simply with the first entry for that year, the soon to be very familiar phrase ‘Light Extinguished at’ (with the time stated), and the proceedings for that day. There are no precursory pages with official details of the staff or harbour, no indication of who is writing. However, other sources have revealed who the harbour masters were throughout certain years.

Captain Eden & Captain Tudor:

After the disaster of Black Saturday in 1848, when thirty-seven lives were lost alongside forty boats, Jean Dunlop states that ‘the Directors [of the British Fisheries Society] realised that their administration of Pulteneytown was inadequate. As early as October 1848, therefore, they discussed the appointment of a naval officer as harbourmaster with complete control of all works connected with the harbour, and four months later, in February 1849, Captain Eden was chosen’[1]. Dunlop continues that ‘soon after Eden’s appointment the Society’s agency, which involved chairmanship of the Pulteneytown Improvements Commission [P.I.C.] among other duties, was combined with that of harbour master’ [2]. This would have put in Eden’s charge responsibility to impose rates on the settlers in return for amenities such as street lighting, cleaning, drains and a police force: the inference being that the post of harbour master was just as much political as it was nautical. Consequently, we hear that in 1854 Eden’s resignation was demanded due to his lack of discretion in dealing with locals and whilst sitting on the board of the P.I.C. He was replaced by a more ‘diplomatic harbour master and agent, Captain Tudor’[3]. Captain John Tudor is likely to have remained harbour master until 1861. He is mentioned by Davies as ‘the Society’s agent’ who played a large part ‘both afloat and on shore, in the early provision of the lifeboat service’ in Wick [4]. Furthermore, we are told that he served as coxswain on the lifeboat from 1848-1861 and that he was ‘awarded two of the early silver medals for gallantry’[5]. This seems to fit nicely with Slater’s Royal National Commercial Directory and Topography of Scotland for 1861 which names James Cormack as harbour master and Captain Tudor as superintendent [6]. It may be that as he stepped down as coxswain on the lifeboat that he also moved from harbour master to superintendent. We may then ascertain that it is Captain John Tudor’s words we will be reading throughout the 1859 entry or at the very least words under his supervision.

James Cormack & William Payne:

On 7th April 1861, when a census was taken, James Cormack would have been fifty-eight years old. He is reported as being deputy harbour master at this time [7]. It would seem likelier still that this was indeed the year he was promoted to harbour master as referenced in the Slater Directory. We also learn that he died in 1876 at the age of seventy-three [8]. It is very probable then that it is entries of his office that we read through December of 1872, detailing a great storm and the subsequent breach of the Stevenson breakwater. His death in 1876 fits well with the Slater Directory for 1878 which names William Payne as the then harbour master. William is also noted as harbour master in the 1886 Slater Directory as well, making him the leading candidate for harbour master throughout the Trawler Riot entries of 1885.

It is impossible to tell without doubt who’s words we are reading, yet we are afforded through the above secondary evidence an idea of what kind of man was given to the position of harbour master and the wide-ranging responsibilities of his post. We can then imagine the implications this would have had on the style and bent of the prose.

Provenance: Private Deposit

The harbour master log books are part of our extensive Wick Harbour Trust collection. The Wick Harbour Trust began as a board of 19 trustees in 1879. They took over administration from the British Fisheries Society whose policies had been deemed unsound; since 1873 the Wick Chamber of Commerce and the local shareholders of the Society had started to demand ‘the transference of harbour management to local representatives’[9]. Their members were thereon elected from local fishing, business and council interests. As of the 1st July 2005, management of the port is now under the new Wick Harbour Authority. The collection was created and kept by the Harbour Trust and their solicitors until deposited with the Caithness Archive in a number of accessions from 1995-2005. The log books are one of numerous items including minute books and registers of vessels, alongside Treasurer’s, engineer’s, property, financial and employee records.

Format: Log Book

A log is an official record of events. Official records should be unbiased and factual. However, all official records are written by individuals; biased, fictitious beasts that they are. Regardless, we may expect a far higher decorum within an official log book than to say a personal diary. There is a perceived public audience with an official record; an agenda at work, whether that of the British Fisheries Society or the Wick Harbour Trust members; standards and regulations to be adhered by. As mentioned above the harbour master was a regulatory presence within the harbour and an influential & political presence within the town. The replacement of Captain Eden with Captain Tudor attests to the expected propriety of such a figure and in many ways we can expect the content of the records to reflect this. The defence of certain vested economic interests is also evident. It is certainly true however, that the great pleasure in reading the harbour master’s log books is that they are often more emotive and descriptive, personable and bold, than might be expected in first discovering them. Within these more honest, perhaps intuitive entries, that capture ongoing periods of unrest or crisis, we hear stories from the archive through the office of an important local figure, often documenting between a formality and a reality.

Harbour Master Log Book 1859

The ‘War of the Orange’ or the ‘Orange Riots’ began on the 27th of August 1859 and continued, with sporadic rises and dissipations of violence, until the 14th of September 1859. The entire proceedings were apparently sparked by a dispute over a piece of fruit (noted by Robert Louis Stevenson to have been in fact an apple), between two young boys (one from Lewis, the other a local of Pulteneytown), that erupted into a violent schism between the locals and the seasonal immigrants. Iain Sutherland has already given a vivid, narrative account of the timeline and so this is not our intention here[10]. Our purpose here is to embellish these often-told stories and legends with strong primary evidence, to invoke the importance of contemporary accounts such as the harbour master log books and the care that must be taken in examining them. We seek not a solid, objective truth but an investigation based on the closest, reliable sources available to us and how they may inform our perceptions. We also want you to get an up close and personal experience with one of our most exciting collections.

Foden tells us that until 1859 there had never been an expectation of violent conflict between the highlanders and the local population[11]. Indeed, the immigrating highlanders were a source of great wealth to Wick, returning year after year during the flourishing herring fishing. Many of the highlanders came from the west coast whilst the locals were often second-generation lowland immigrants. There was certainly a lack of assimilation, due to their respective origins, which caused considerable divisions between the groups of both language and culture. Their differences in outlook must surely have been palpable. However, the economic gains to be had and a general air of civility seem to have kept a peace between them until 1859. The local newspapers, The John O’Groat Journal and the Northern Ensign were known to have very differing views on the affair with the Ensign ‘taking the tolerant view, pointing out there had never before been serious trouble’, whilst the Groat declared that ‘greater severity in the handling of the visitors had long been called for’[12]. Again, in search of answers we find only more heated opinions.

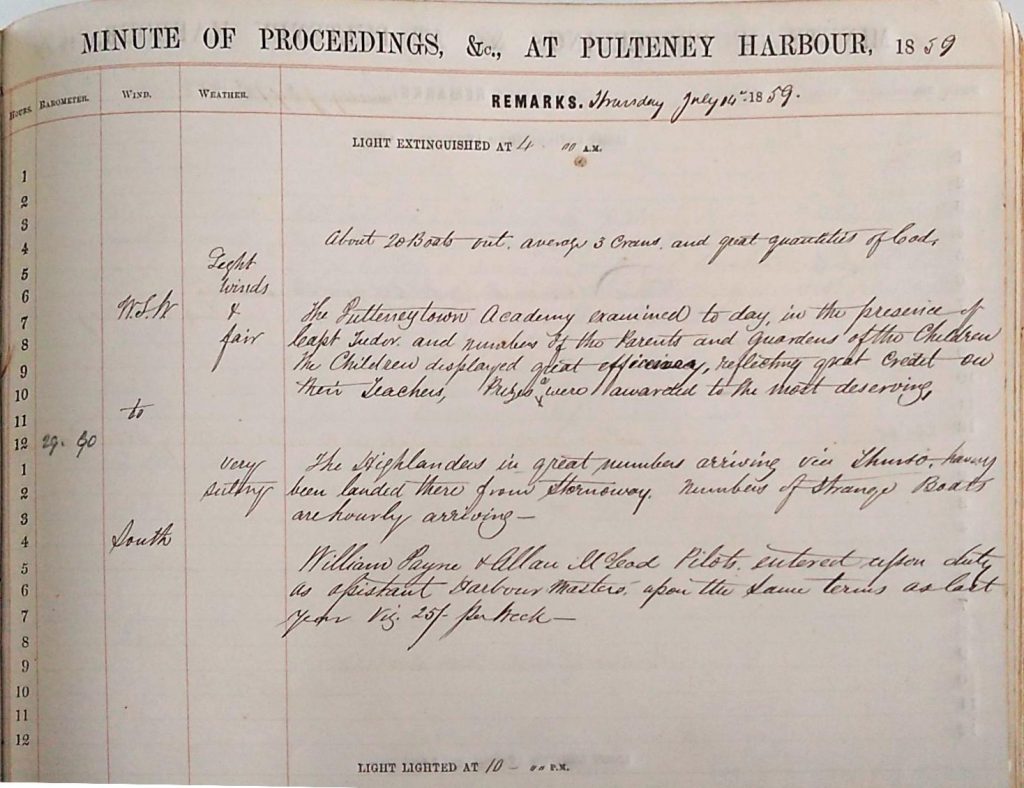

The herring season would often start around July and the first image below (click to enlarge) is from the entry for the 14th of July 1859. In it we are told there were roughly ’20 boats out, average 3 crans and great quantities of Cod’. A cran was a unit of measurement for landed, uncleaned herring and equated to around 37.5 imperial gallons or typically 1,200 fish (but could vary from 700 to 2,500)[13]. The author then tells us that the Pulteneytown Academy was examined today ‘in the presence of Capt. Tudor’. As discussed above it is most likely that Captain Tudor was harbour master at this time. Was someone else writing the log under his supervision? Did he enjoy referring to himself in the third person? Was he in fact not the harbour master? It is impossible to tell from the evidence we have and often these little mysteries must go unanswered. It does seem most likely that he was the harbour master but that he may not have been the direct author of the log book. More importantly, we are told on the 14th that ‘the highlanders in great numbers [are] arriving in Thurso, having been landed there from Stornoway. Numbers of strange boats are hourly arriving’. It seems the yearly immigration had begun, and it is clear the writer does not consider himself to be a highlander. The use of this terminology exemplifies a clear divide, an otherness. Having arrived in Thurso most of the highlanders would then walk to Wick. The success offered by the herring season at Wick seems distinct when we consider the enormity of their journey and the months spent away from home every year.

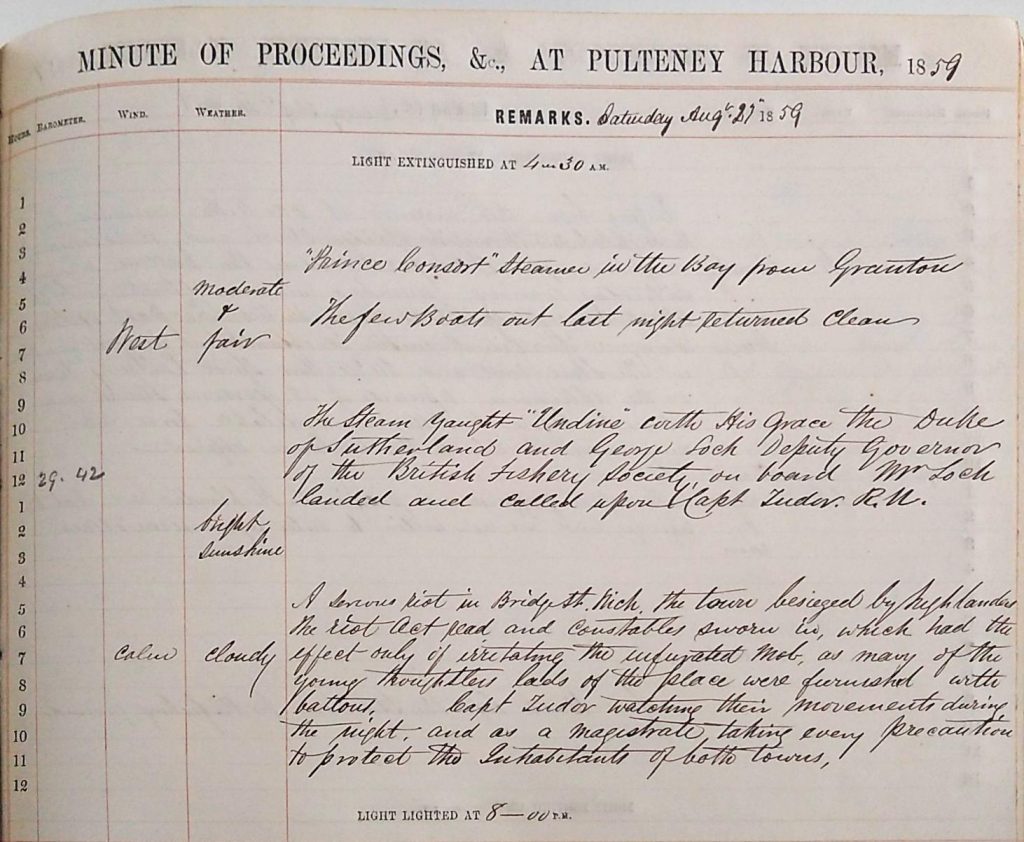

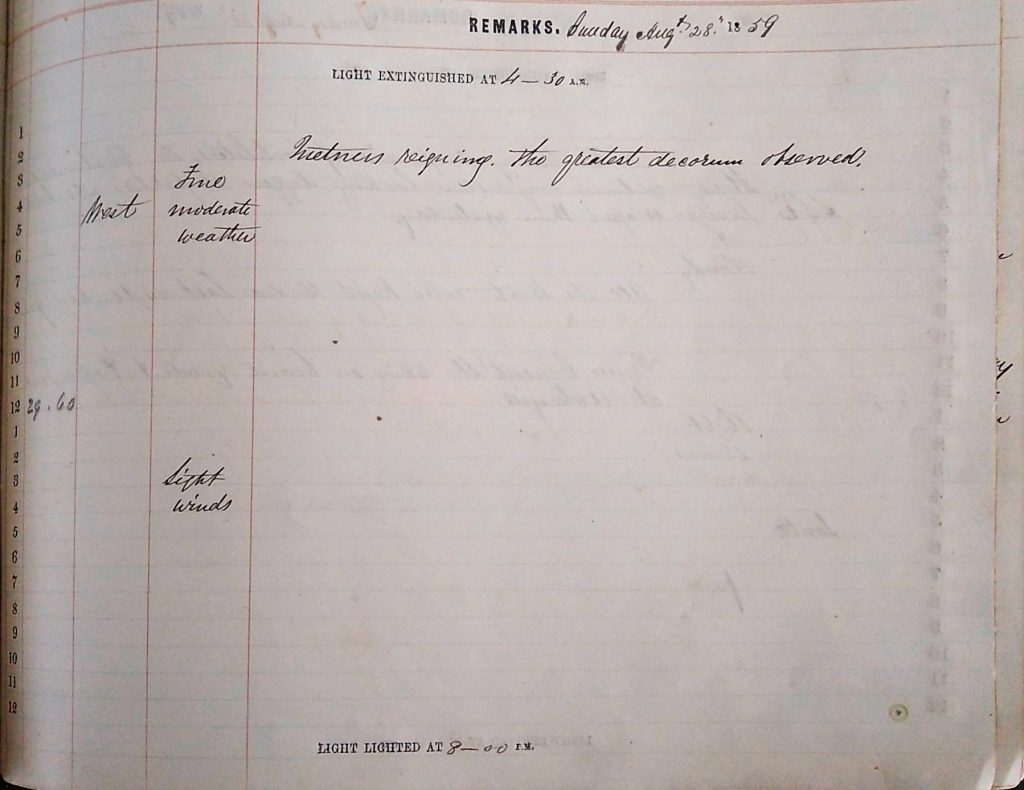

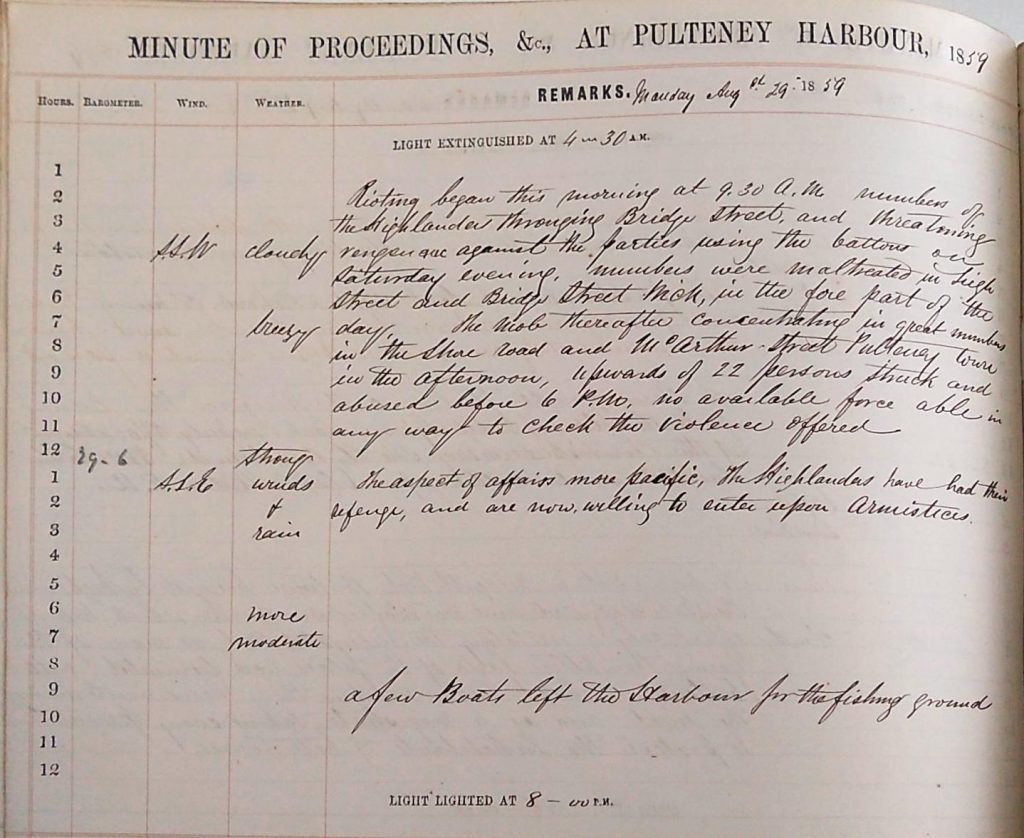

The riots themselves began on the 27th of August with the log book recording ‘a serious riot in Bridge St. Wick, the town besieged with highlanders, the Riot Act read and constables sworn in, which had the effect only of irritating the infuriated mob, as many of the young thoughtless lads of the place were furnished with battons [sic], Capt. Tudor watching their movements during the night, and as a magistrate taking every precaution to protect the inhabitants of both towns’. Captain Tudor’s prominence within the community and direct involvement is confirmed here, as is the political nature of the log book itself and the inherent bias its entries are functioning within. We are given no indication of why the rioting began, only that it is the highlanders who are the perpetrators. The following day the violence ebbs for the first time with ‘quietness reigning, the greatest decorum observed’.

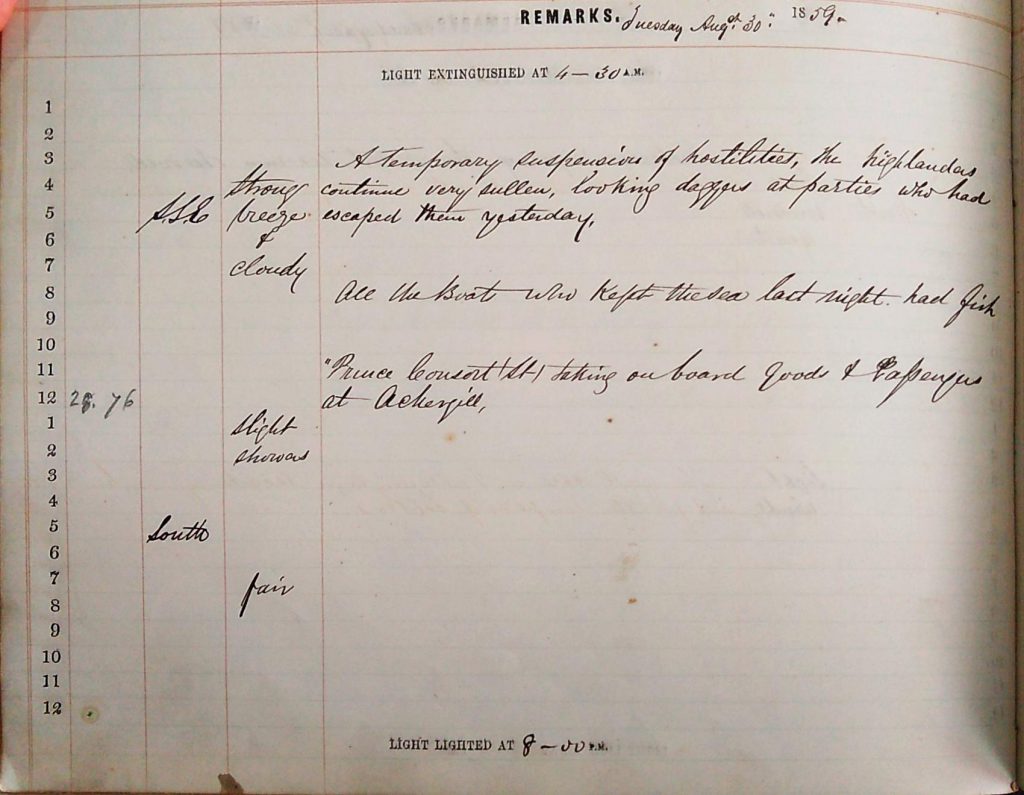

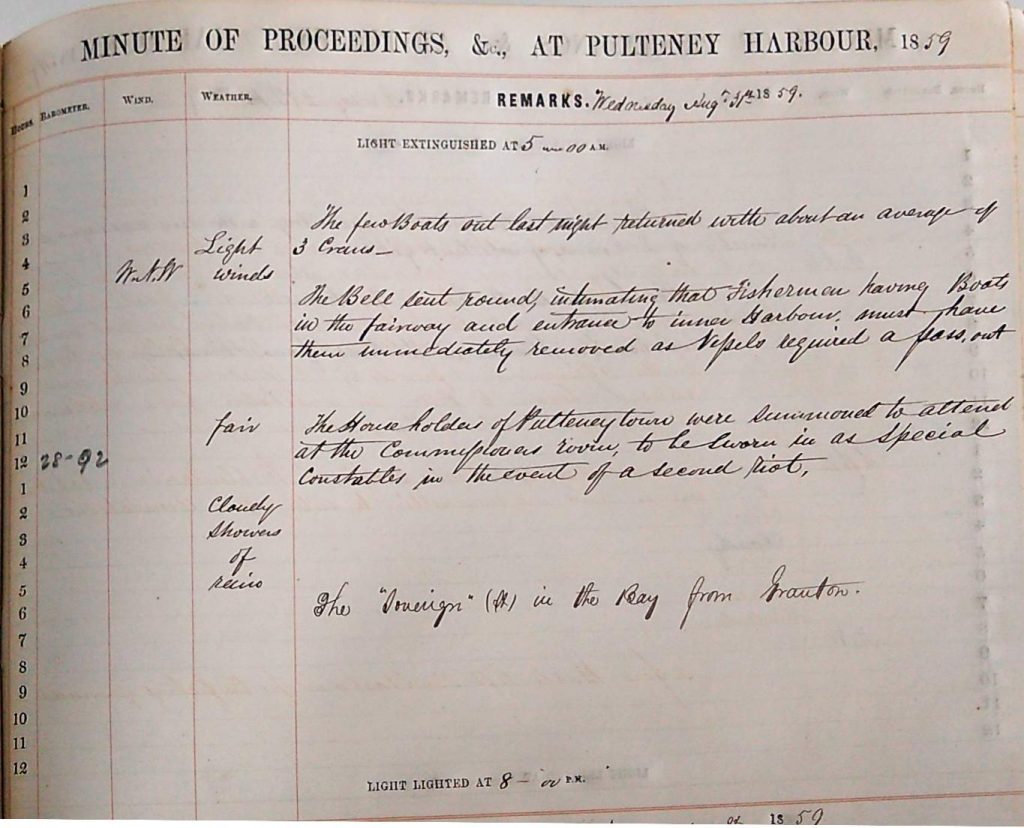

Rioting resumes from 9.30am on Monday 29th with highlanders ‘threatening vengeance against the parties using the batons on Saturday evening’, the ‘thoughtless lads’ earlier referred to. Many are maltreated throughout the day with ‘upwards of 22 persons struck and abused before 6 P.M., no available force able in any way to check the violence offered’. The lack of a substantial police force is apparent here, yet it is also telling that one was not considered pertinent until the riots began. This seems to be a rare and unexpected case of social unrest. The 30th sees another ‘temporary suspension of hostilities, the Highlanders continue very sullen, looking daggers at parties who had escaped them yesterday’. The author is creating a very vivid image of a violent, untrustworthy highlander; admissions that seem far from a log book’s purview.

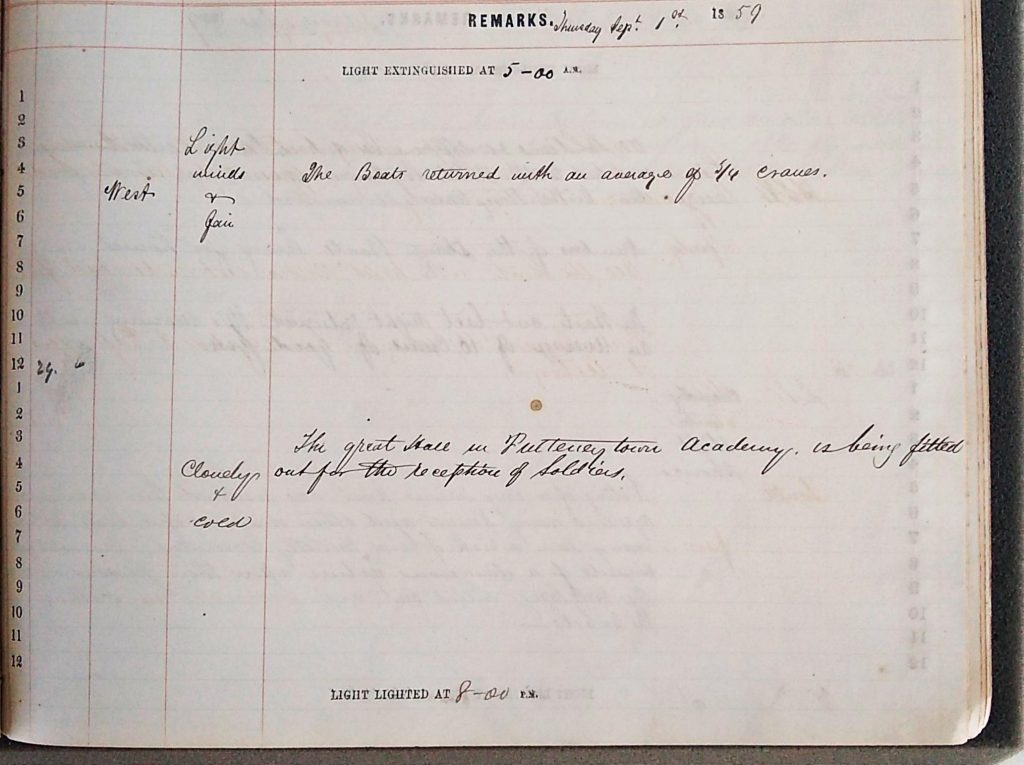

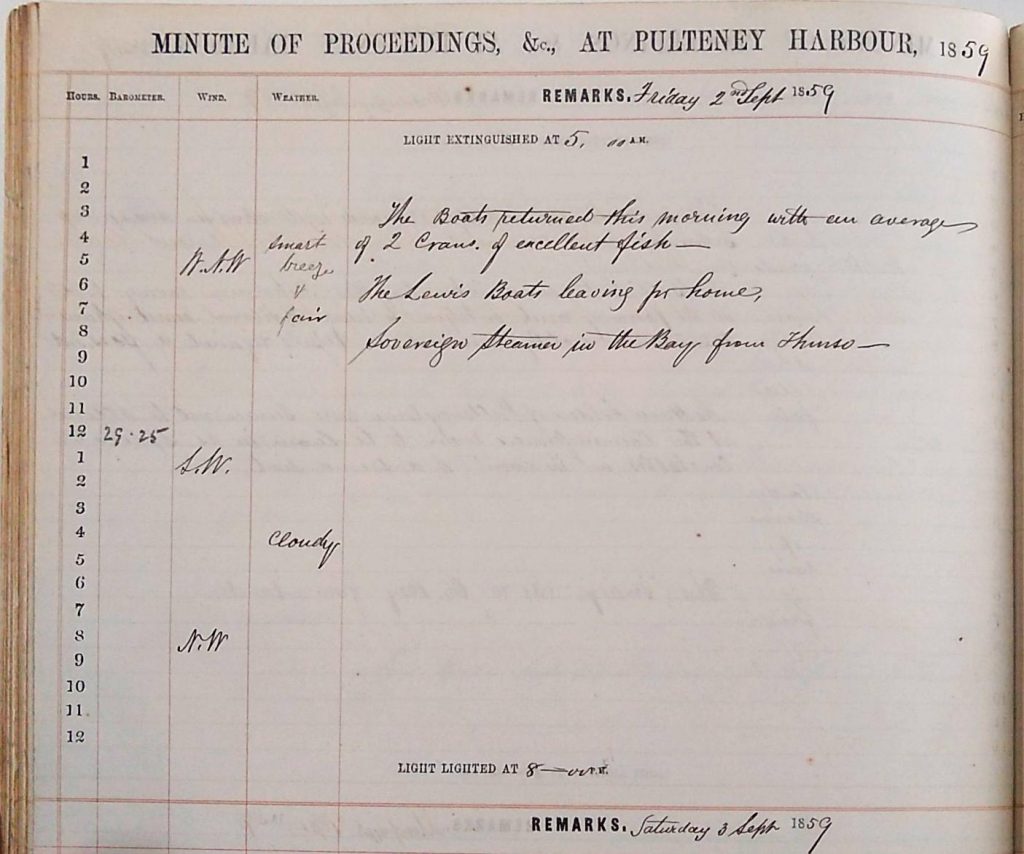

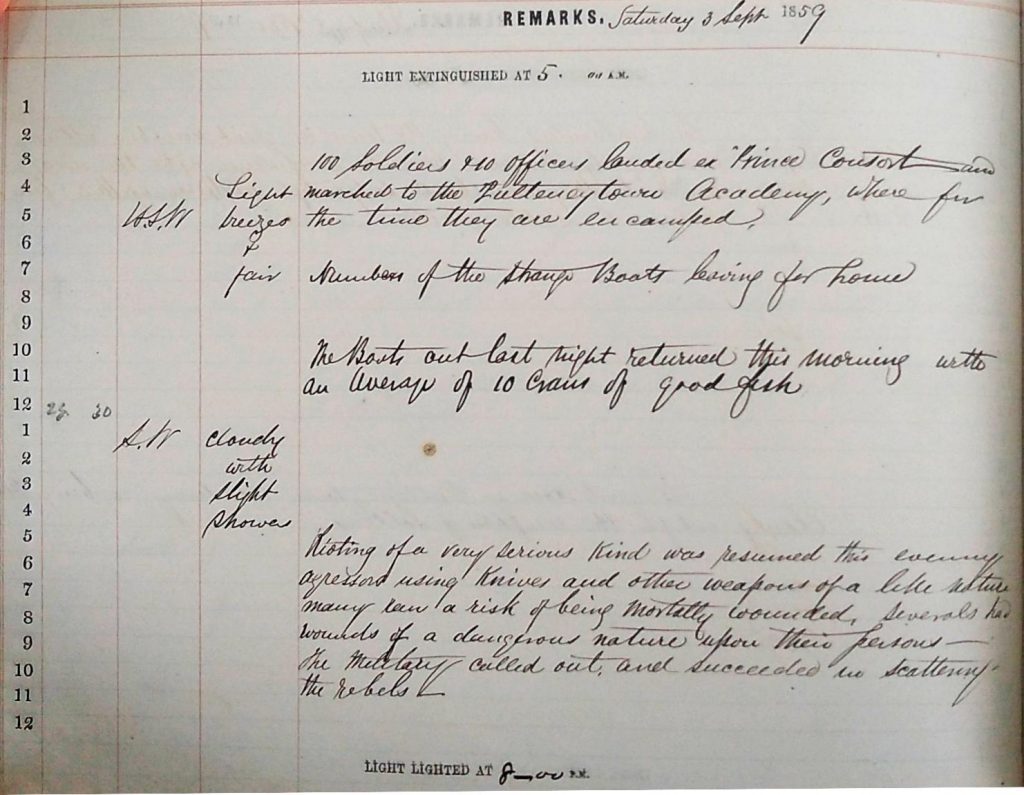

Throughout the rioting boats continue to leave for the fishing grounds and their average crans are recorded. The juxtaposition of entries such as, ‘the boats returned with an average of 5/4 crans’ and ‘the great hall at Pulteneytown Academy is being fitted out for the reception of soldiers’, on September 1st is quietly unsettling. On the 2nd we are told that the ‘Lewis boats [are] leaving for home’. ‘Numbers of the strange boats’ continue to leave for home on the 3rd whilst ‘100 soldiers & 10 officers landed on “Prince Consort” and marched to the Pulteneytown Academy’. These boats appear to be leaving early to avoid further confrontation as some people had been attacked in Pulteneytown ‘just because they were speaking Gaelic’[14]. They escaped just before, ‘rioting of a very serious kind was resumed this evening, aggressors using knives and other weapons of a like nature, many ran a risk of being mortally wounded, several had wounds of a dangerous nature upon their persons. The military called out and succeeded in scattering the rebels’.

By the 5th of September ‘The Highlanders [are] leaving the town in great numbers’ and on the 7th ‘the larger portion of the boats have left for home’, cutting their fishing season short. This, as Foden remarks, was really the end of the ‘Orange Riots’[15]. Patrols continued for another week or so and the need for a better organised police force was confirmed. Animosity however, seemed to dissipate quickly between locals and highlanders with Sutherland commenting that many local folk, ‘were so ashamed and horrified by the cowardly nature of the attacks that they put down their weapons and carried the injured into their homes to attend to their wounds. Women seem to have taken the initiative in this’[16]. The following year the highlanders returned and the herring boom in Wick continued. In this way a greater sense of humanity seems to have shone through whilst past recriminations were forgotten. The violence and bloodshed described however, are a reminder both of the cultural divide that existed between the locals and the highlanders and the political avarice that pumped through the veins of the profitable herring trade.

Harbour Master Log Book 1872

For a time during the 19th century, Wick was the largest herring fishery in Europe. The old harbour was completed in 1811 and the new outer harbour between 1825 and 1834 by civil engineer James Bremner[17] who had also supervised the construction of ‘Ham, Castlehill and Sandside in Caithness and Lossiemouth, Banff and Buckie on the south side of the Moray Firth’[18]. However, at Wick the ‘fishery had vastly outgrown the capacity of the harbours, from which more than 1000 boats were fishing in 1862’ and subsequently D. & T. Stevenson of Edinburgh were commissioned to design a breakwater that would protect a third harbour[19].

‘The sea proved too strong for man’s arts’ [20], lamented Robert Louis Stevenson in the essay he wrote on his father. Indeed, Thomas Stevenson’s attempt to build a breakwater in Wick harbour would stand as ‘the chief disaster’[21] of his life. Speculation as to the cause of the breakwater’s multiple failures between 1861 and 1875 is still rampant today and it is not our intention here to answer this mystery. Instead, we wish to present an astonishing account of the week long storm that rocked Wick harbour in December of 1872. Again, the harbour master log books step beyond their professional purview to bless us with a harrowingly embellished account of the calamity.

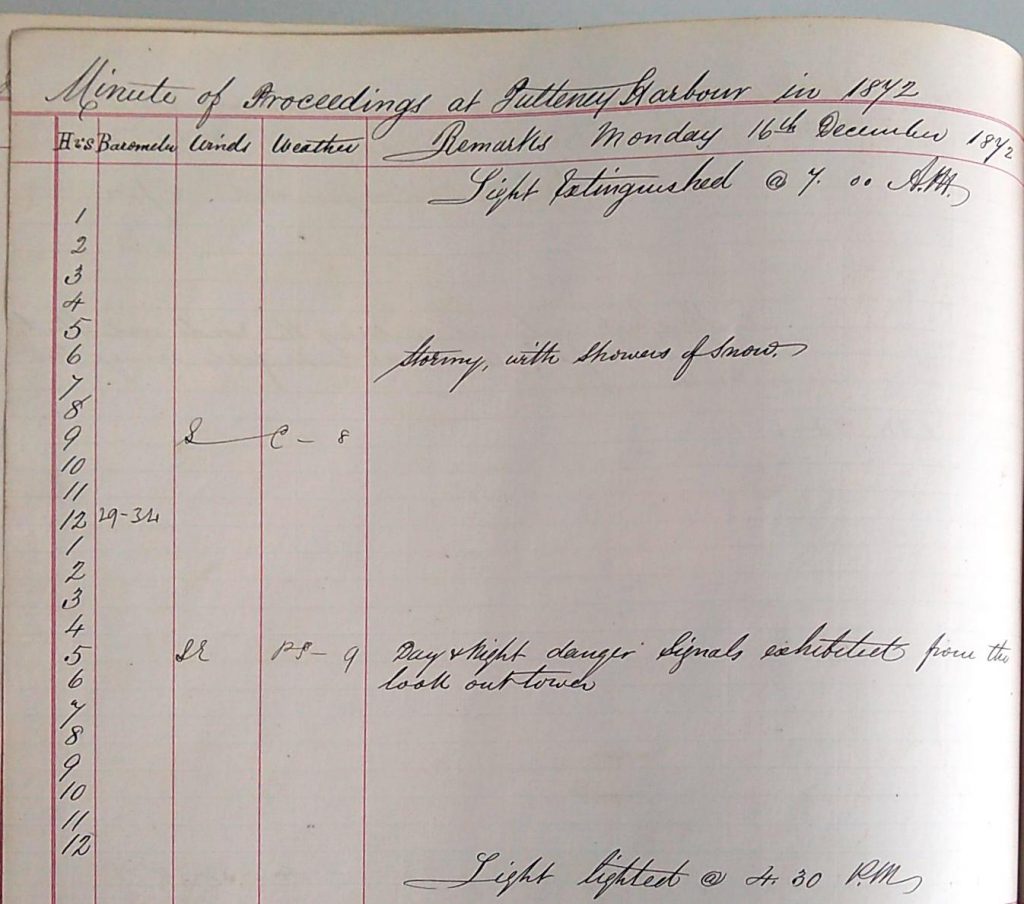

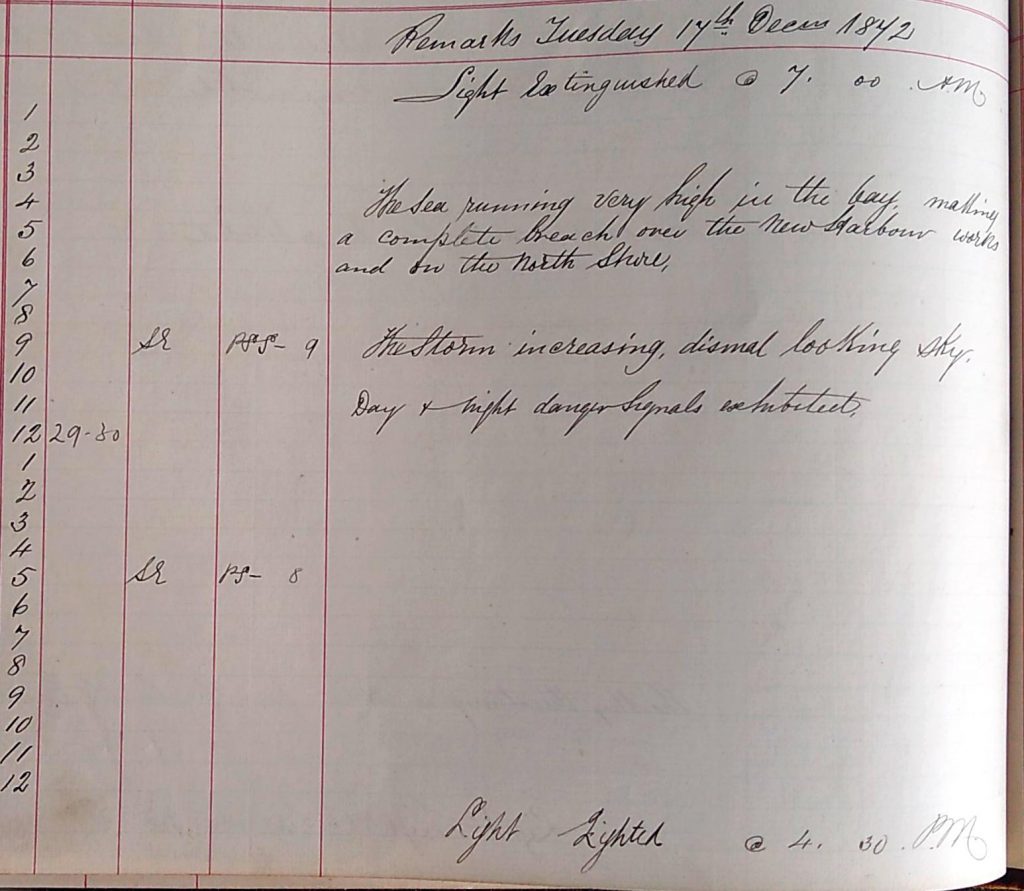

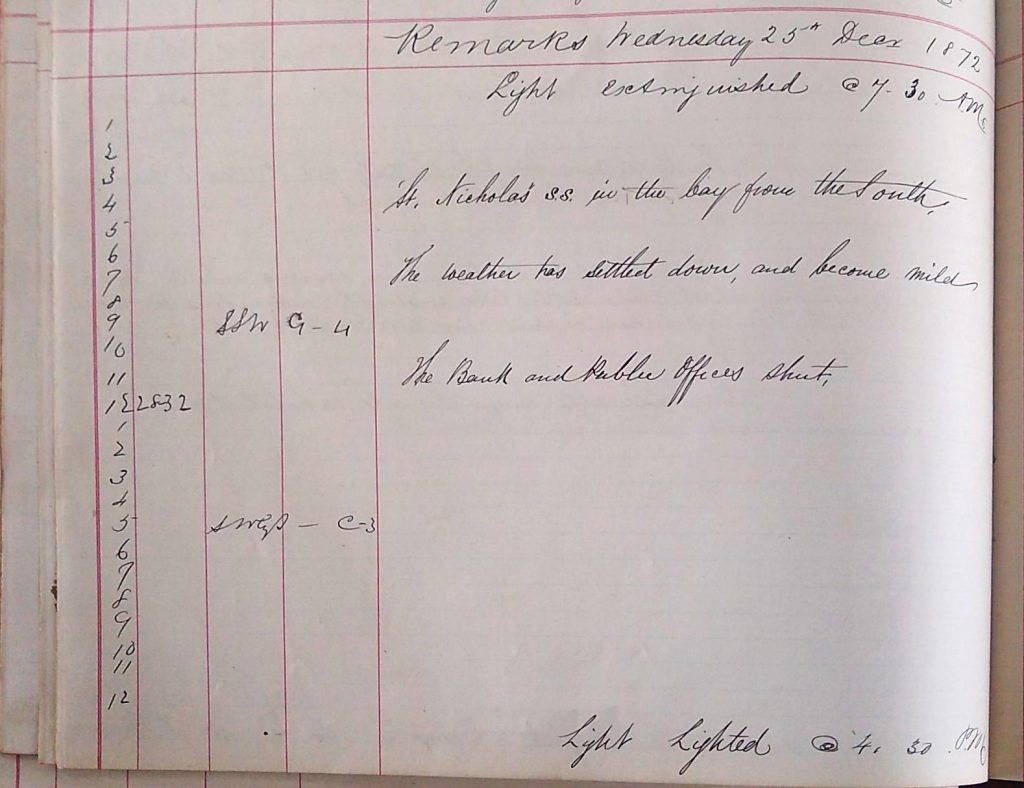

The first image below is for the 16th of December 1872. The short winter days are evident by the light not being extinguished until 0700am and then lighted again at 0430pm. The weather is ‘stormy, with showers of snow’ and ‘day & night danger signals [are] exhibited from the look out tower’. This ominous tone continues through the 17th with ‘the sea running very high in the bay, making a complete breach over the new harbour works and on the north shore’. The storm is increasing within a ‘dismal looking sky’ and the warning light continues to burn ‘day & night’.

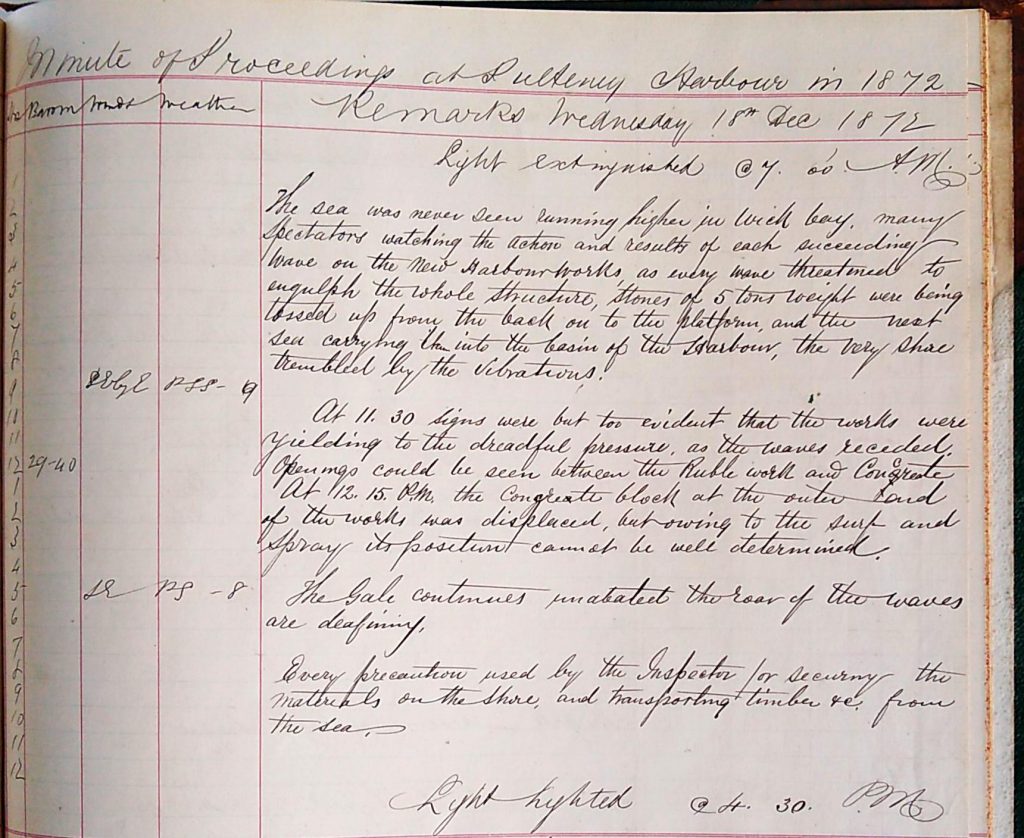

A lengthy entry on the 18th reads as though from one of Stevenson’s novels itself: ‘the sea was never seen running higher in Wick bay, many spectators watching the action and results of each succeeding wave on the new harbour works as every wave threatened to engulph [sic] the whole structure, stones of 5 tons weight were being tossed up from the back on to the platform, and the next sea carrying them into the basin of the harbour, the very shore trembled by the vibrations!’. To find such emotion and description within a log book is overwhelmingly gratifying and we feel almost transported to the past, standing stricken by the shore, the sea so clearly a leviathan in the lives of all who lived alongside it. By 1130 ‘signs were but too evident that the works were yielding to the dreadful pressure’ and at 1215 ‘the concrete block at the outer end of the works was displaced, but owing to the surf and spray its position cannot be well determined’. The gale continues ‘unabated, the roar of the waves are deafening’ with ‘every precaution used by the Inspector for securing the materials on the shore’.

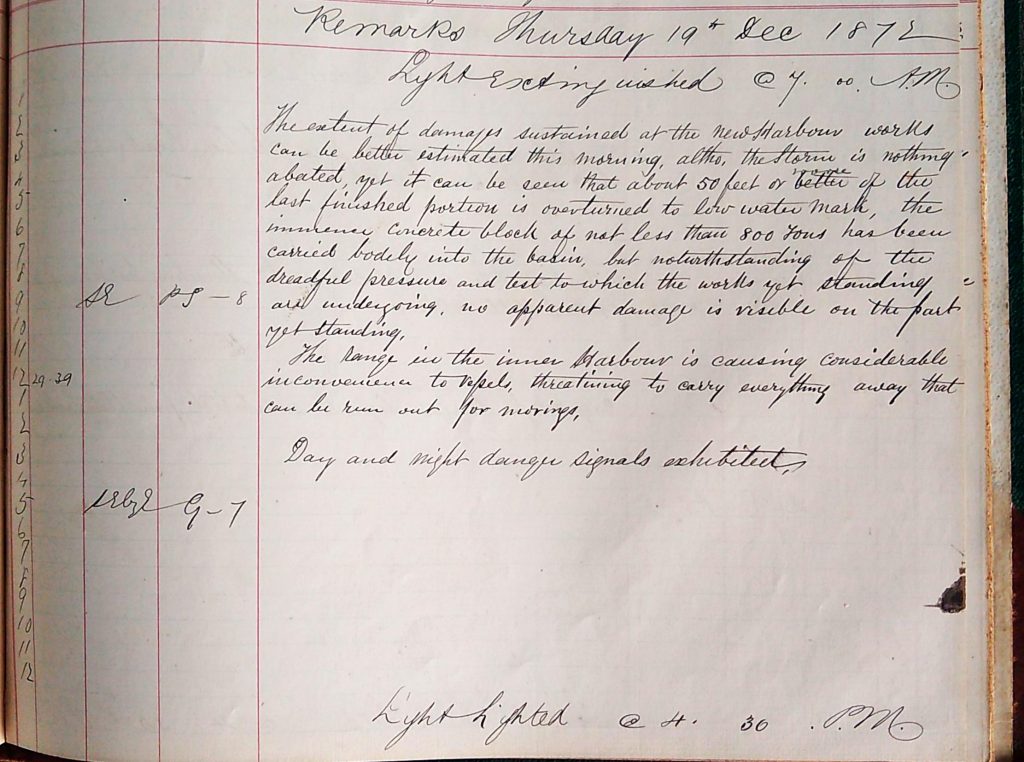

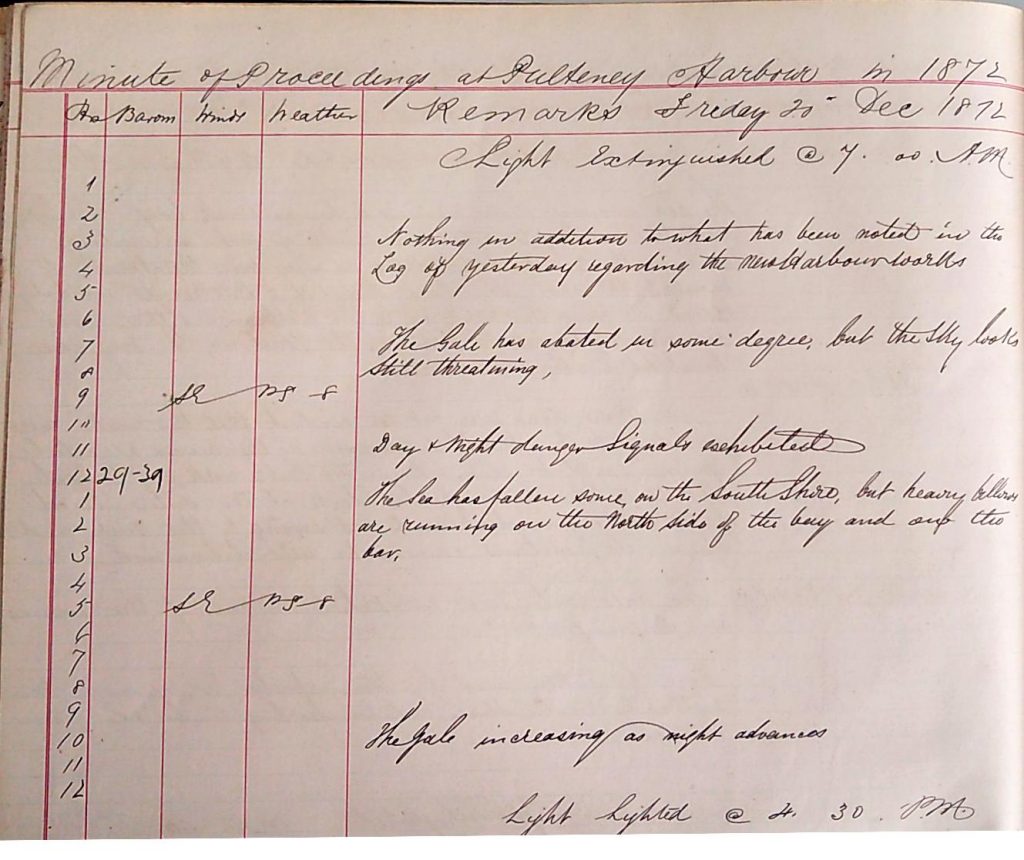

Danger signals continue to be exhibited on the 19th and the extent of the damage ‘can be better estimated this morning, altho [sic], the storm is nothing abated, yet it can be seen that about 50 feet or more of the last finished portion is overturned to [the] low water mark, the immense concrete block of no less than 800 tons has been carried bodily into the basin’. The ‘dreadful pressure and test’ to which the breakwater is being exposed is made abundantly plain. On the 20th the sea falls and the gale abates ‘in some degree’. However, the still threatening sky is a forewarning as ‘the gale [again] increases as night advances’.

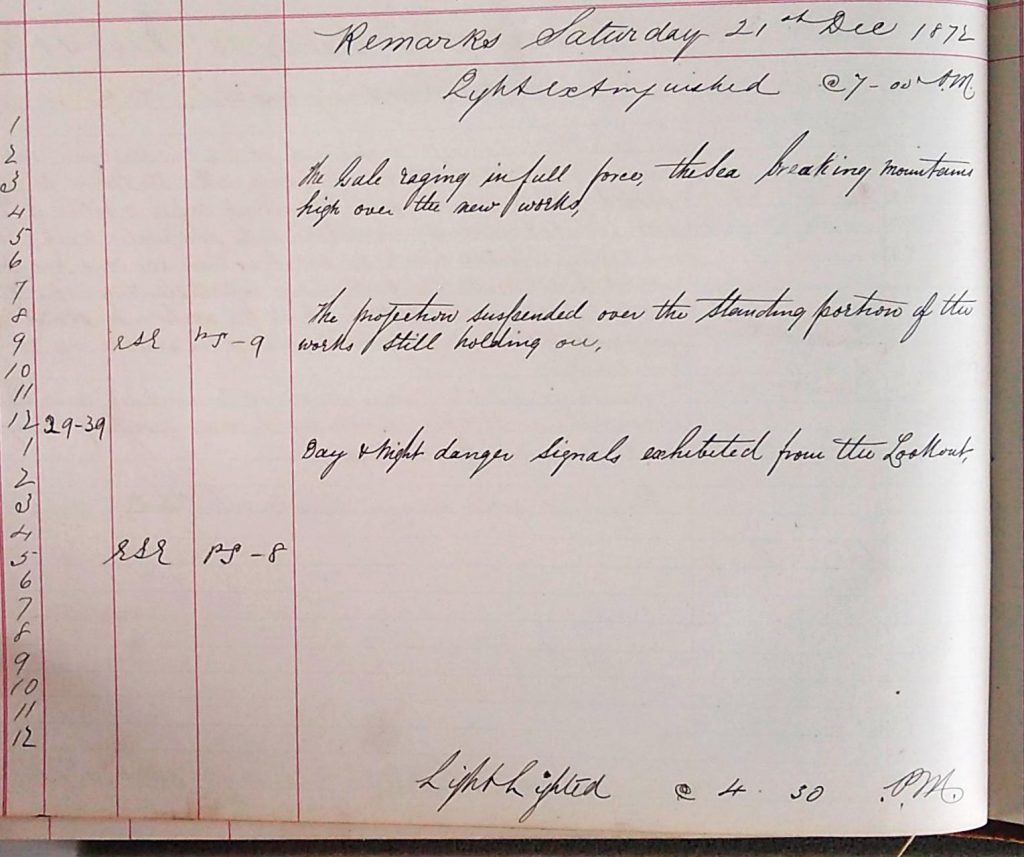

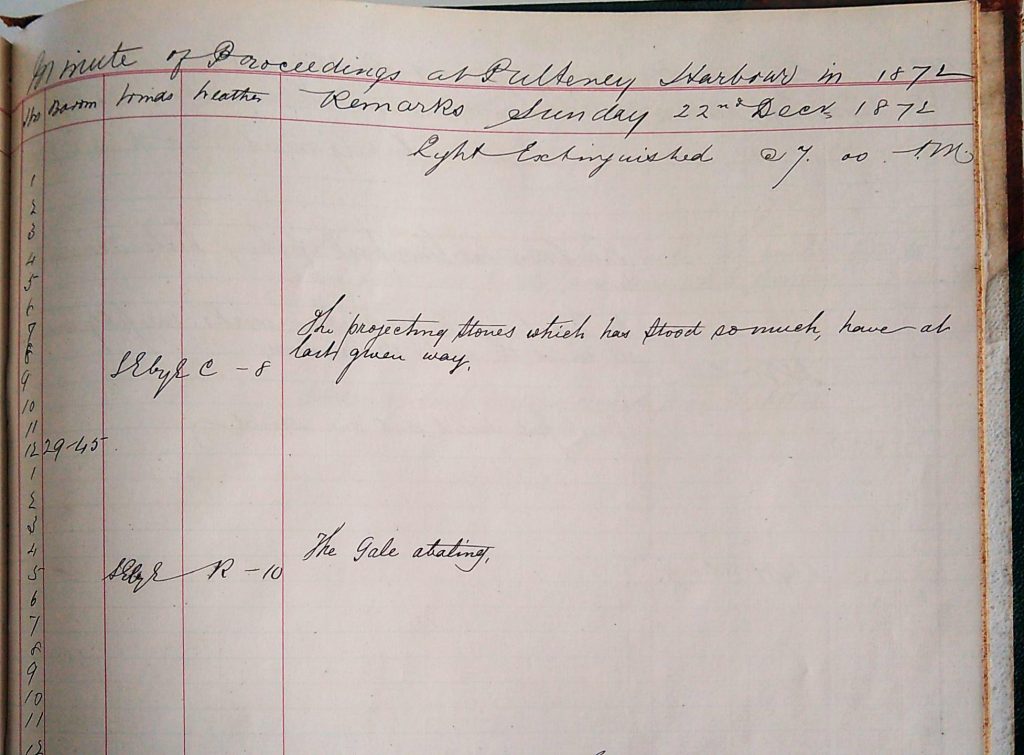

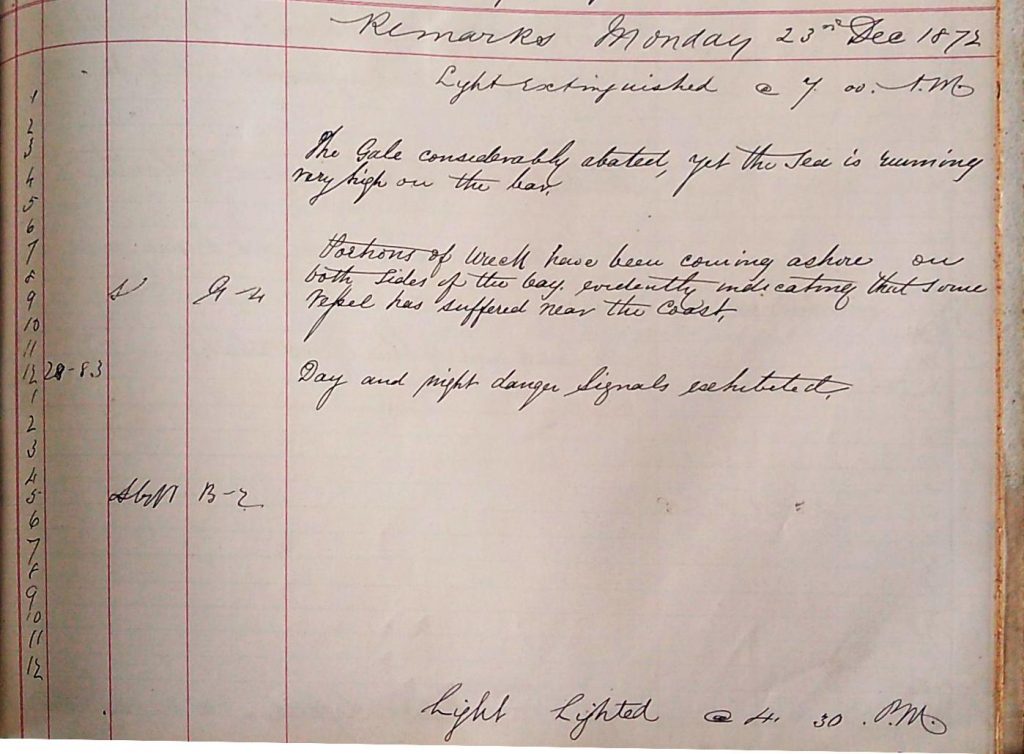

By the 21st the storm is again ‘raging in full force, the sea breaking mountains high over the new works’. By some luck the projecting stones ‘over the standing portion of the works [are] still holding on’. However, on the 22nd these stones ‘which have stood so much, have at last given way’. Through the night of the 22nd and into the morning of the 23rd the gale slowly relents but the sea ‘is running very high over the bar’. The consequences of the storm further out at sea start to reveal themselves: ‘portions of wreck have been coming ashore on both sides of the bay, evidently indicating that some vessel has suffered near the coast’.

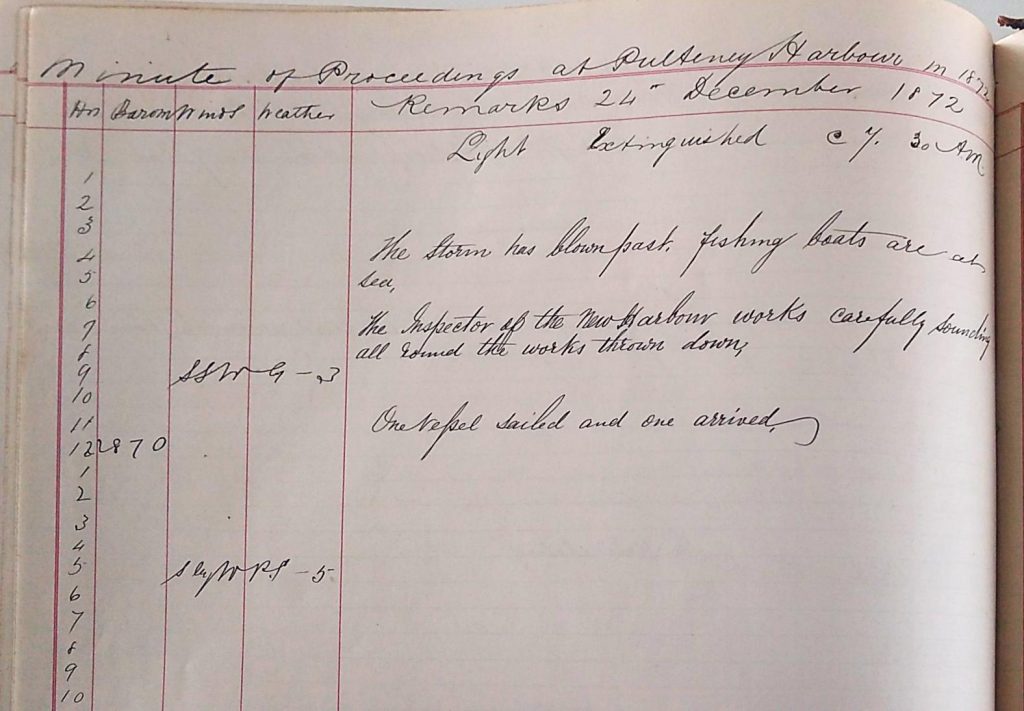

On the morning of the 24th the log book announces that ‘the storm has blown past, fishing boats are at sea’. The Inspector of the new harbour works is ‘carefully sounding all round the works thrown down’ and ‘one vessel sailed and one arrived’. Finally, on the 25th we are told that the ‘weather has settled down and become mild’, perhaps a much-appreciated Christmas gift.

These entries document just one of several repeated damages sustained by the breakwater until it was finally abandoned in 1877. Paxton explains that failures such as that of 1872 ‘arose from the displacement by the sea of the remedial ends which opened up the adjoining work to erosion’[22]. Damage was caused by the air compressed in the waves, which forced itself into tiny gaps and wrenched the masonry apart. Moreover, the force of the 1872 event was about 290 kNm², ‘overcoming a horizontal resistance of 110 kNm² to slew the 1372-ton end’[23]. The unbelievable force and danger posed by the waves is incredible and we begin to understand Stevenson’s inability to tame the wild seas entering Wick bay. This account within the log book of 1872 is priceless and seeing it handwritten on the page seems a special privilege indeed. It also takes us away from the political aspects of the harbour master’s post to the impositions of another foe: the indomitable sea.

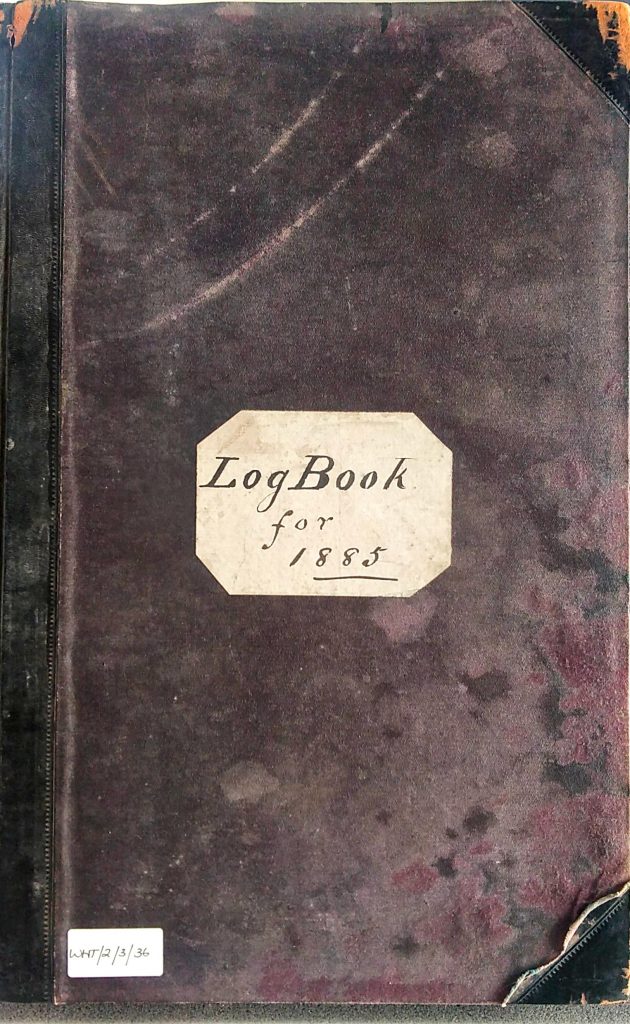

Harbour Master Log Book 1885

‘As it is, I fear the great Wick fishery must come some day to an end. When the Wick fishery first began the fisherman could carry in a creel on his back the nets he required; now he requires a cart and a good strong horse’[24]. These are the prophetic words of James G. Bartram, writing prior to the 1885 ‘Trawler Riots’. Concern regarding overfishing was a growing anxiety amongst local fisherman in Caithness by the mid-19th century, especially the ‘depredations caused by trawlers’[25]. Trawling involved towing a net towards the sea bed. On the one hand it was far more profitable to catch bottom feeding fish, but it also killed trillions of spawn and sharply hastened the loss of local fish stock. A letter was sent to the editor of the Northern Ensign on 22nd February 1884, signed ‘Forss Fishermen’ of Latheron. Having no formal organisation these men appealed to their local newspaper detailing:

‘To the legislature we need not apply for they are already aware of what destruction has been done to net and line fishing on every coast where trawling has been prosecuted. I think it is worse than useless to apply to our M.P. for giving us any support in our difficulties as he recommended Sabbath fishing a few years ago. Steam trawlers suit his purpose. It is shameful and degrading to see, as we see from our doors, the Lord’s Day being desecrated by these people, a sight unseen and unknown to us heretofore. We wonder how the rulers of our land can boast of their Civilisation and Christianity when such nefarious work as trawling is allowed to be carried out on the whole of the Sabbath day. The heathen whom we despise can do no more. It is well known that it is from our fishing that we pay our high rents for our crofts and homes and supporting and bringing up our families. If we are to be deprived of our July and August fishings, as we have of our winter fishings, there is nothing else to be looked for but wholesale pauperism and starvation. We cannot give any other name to trawling as far as we have seen of it yet, but the besom of destruction.’[26]

Many of these same communities had been driven from their homes on inland estates to settle at the coast, now they were once again facing deprivation in the face of mindless profiteering. Undeniably, clearances leading up to the 1880s and their prominence, especially amongst such crofter/fishermen, would have fuelled the public disquiet that was accelerating. Many families made harrowing journeys across the globe or to the industrial centres of the central belt in hope of better fortune. These fisherman however, wished to defend their right to live and work by the sea.

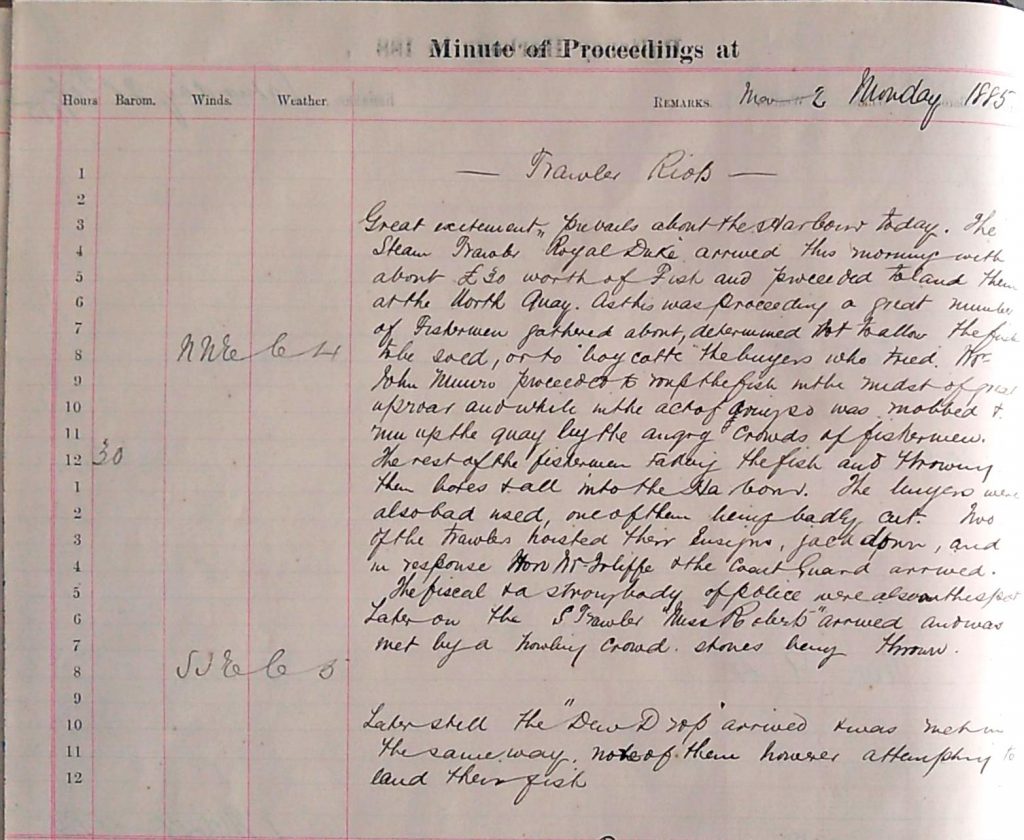

The following year in March of 1885 riots broke out in Pulteneytown harbour as tensions snapped and local fisherman would suffer the greed of trawling no longer. The harbour master log book entry for the 2nd of March 1885 begins with the heading ‘- Trawler Riots -‘. It is very unusual to see a contemporary event titled in this way, revealing how discernible the hatred of trawler fishing must have been. We are told that ‘the steam trawler “Royal Duke” arrived this morning with about £30 worth of fish and proceeded to land them at the North Quay’. However, a ‘great number of fishermen gathered about determined not to allow the fish to be sold, or to boycotte [sic] the buyers who tried’. ‘Great uproar’ ascended upon the quay with ‘angry crowds of fishermen… taking the fish and throwing them boxes an all into the harbour’. A ‘strong body of police’ were assembled and later when another steam trawler arrived it was ‘met by a howling crowd, stones being thrown’.

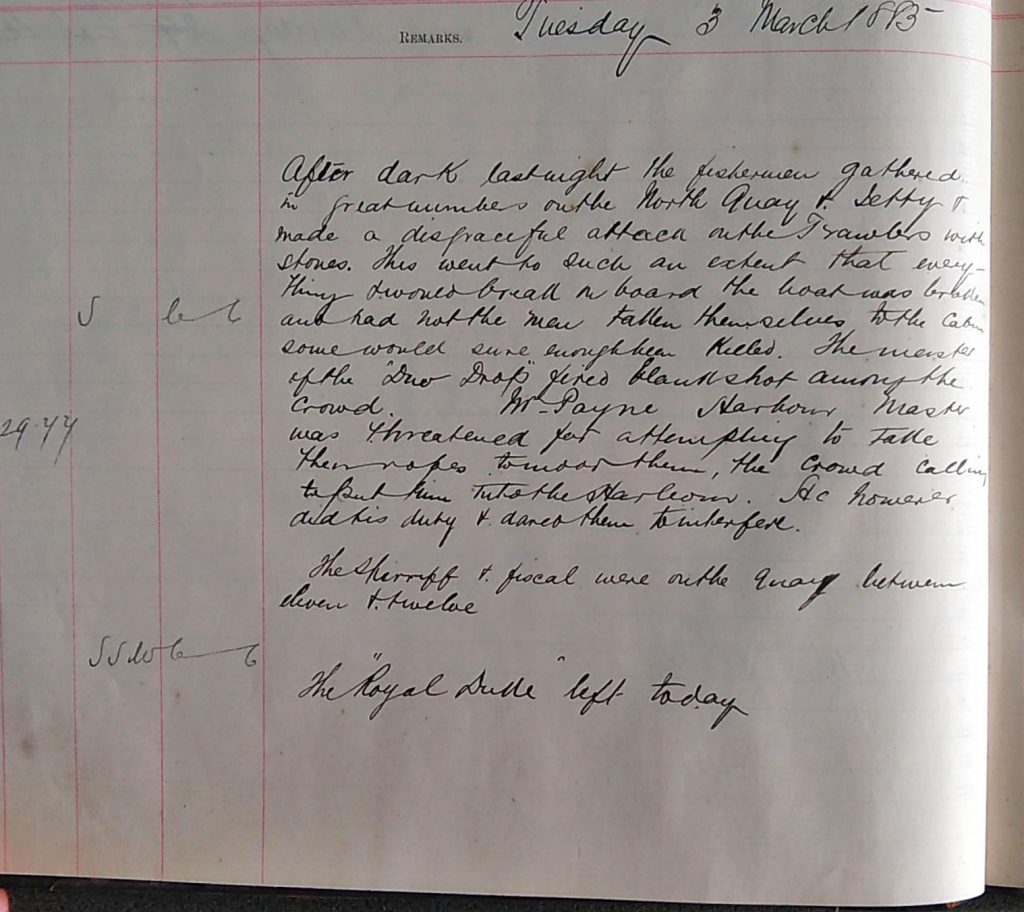

After night had fallen on the 2nd the rioting continued. The entry for the 3rd explains that ‘after dark last night the fisherman… made a disgraceful attack on the Trawlers with stones’. Again, the political bent of the harbour master’s office is clear, with apparently little sympathy for the plight of the local fishermen. Nevertheless, we are then told that the attacks ‘went to such an extent that everything… on board the boat was broken and had the men not fallen themselves to the cabin some would sure enough have been killed’. Furthermore, ‘Mr Payne [the] harbour master was threatened’ whilst taking ropes to the trawlers but we are told that he ‘did his duty and dared them to interfere’. A very brave and formidable depiction, however biased. Later, the sheriff and the fiscal are present on the quay from eleven till twelve at night and the steam trawler ‘Royal Duke’ understandably leaves the harbour.

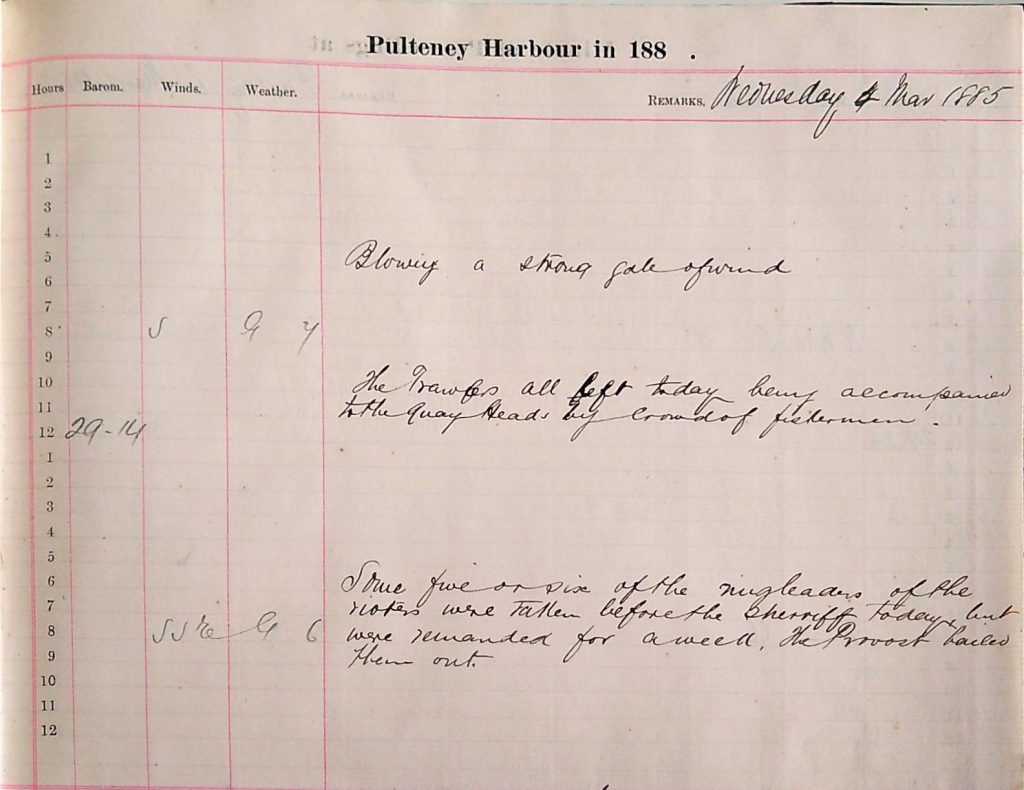

A ‘strong gale of wind’ is blowing on the 4th and all the trawlers leave the harbour ‘accompanied to the quay heads by crowds of fishermen’. Meanwhile ‘some five or six of the ringleaders of the riots were taken before the sheriff’ but were ‘remanded for a week, the Provost bailed them out’. On the 12th of March the John O’Groat Journal reported on ‘The Recent Attack on Trawlers at Wick’ saying that ‘before too hastily condemning’ the fishermen, that ‘the cause of all this outburst must be taken into consideration’. It seems even the local papers were on the side of the fishermen, some of whom received ’30 days in prison for their pains’[27].

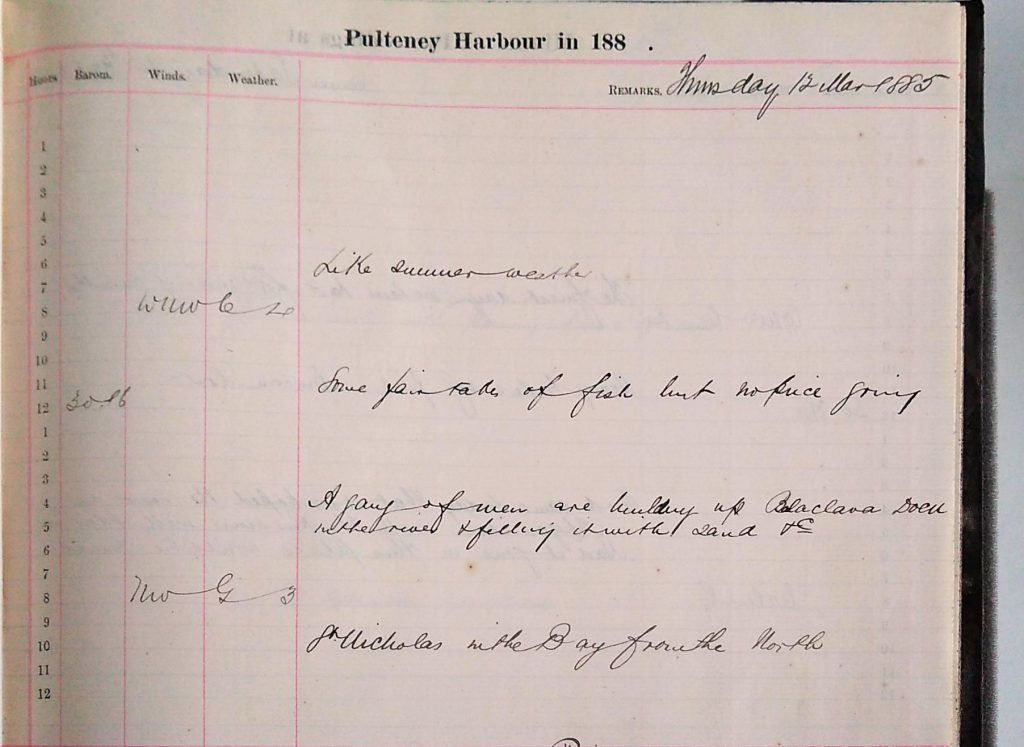

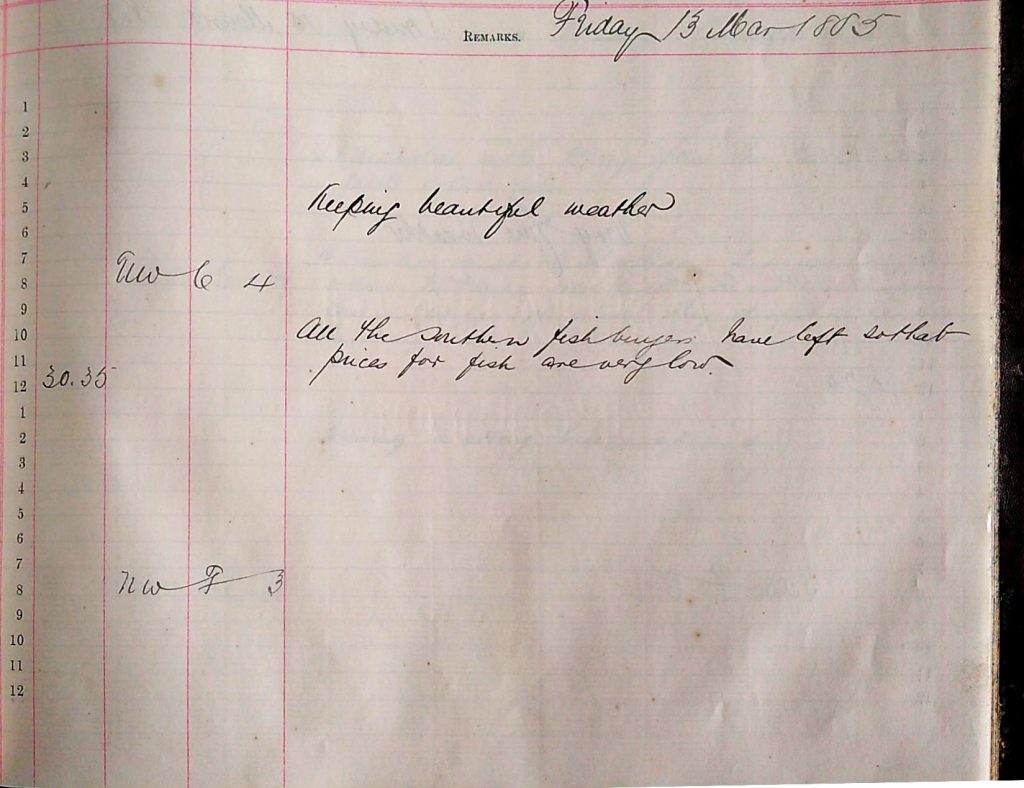

On the same day the paper was published the log book records ‘a gang of men are building up Balaclava Dock in the river & filling it with sand’. By the 13th ‘all the southern fish buyers have left so that prices for fish are very low’. It would seem surprising if this was not directly linked to the rioting.

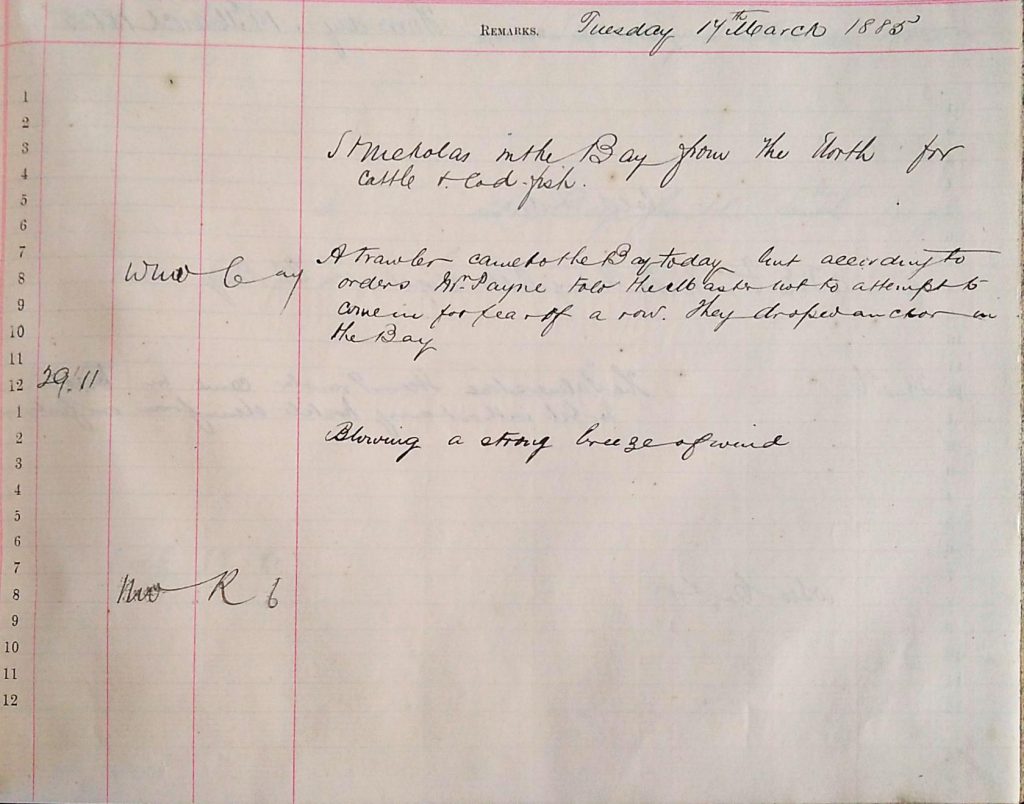

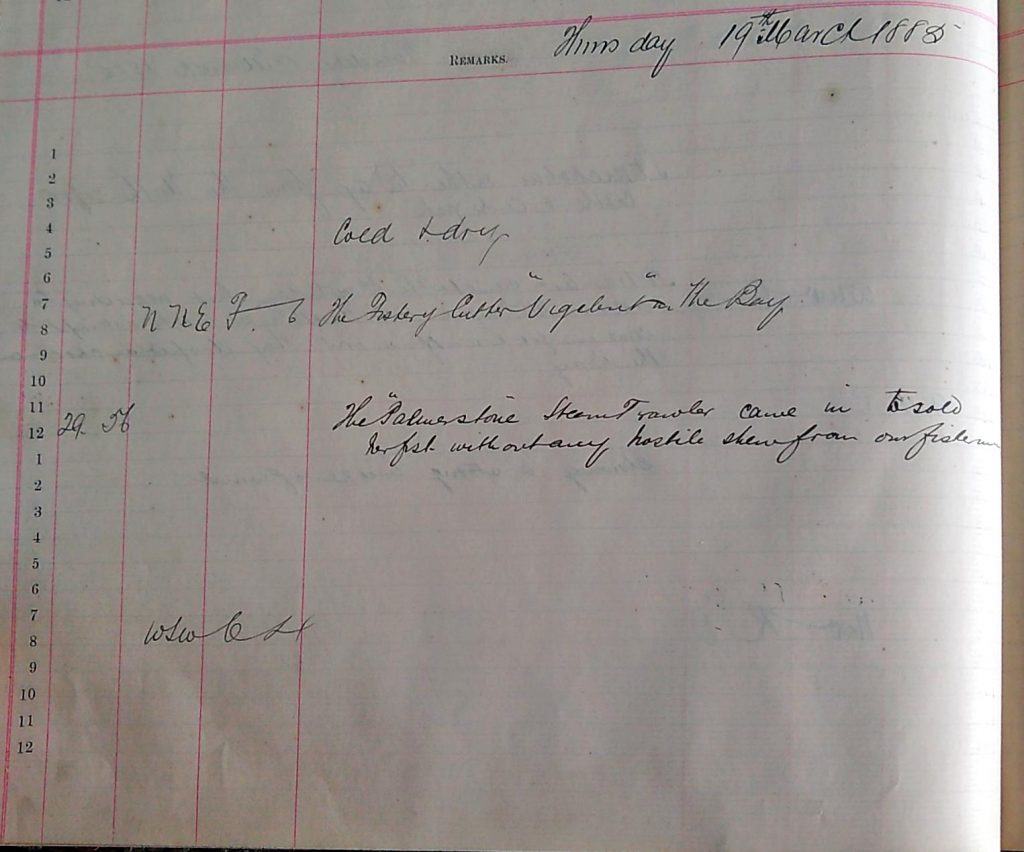

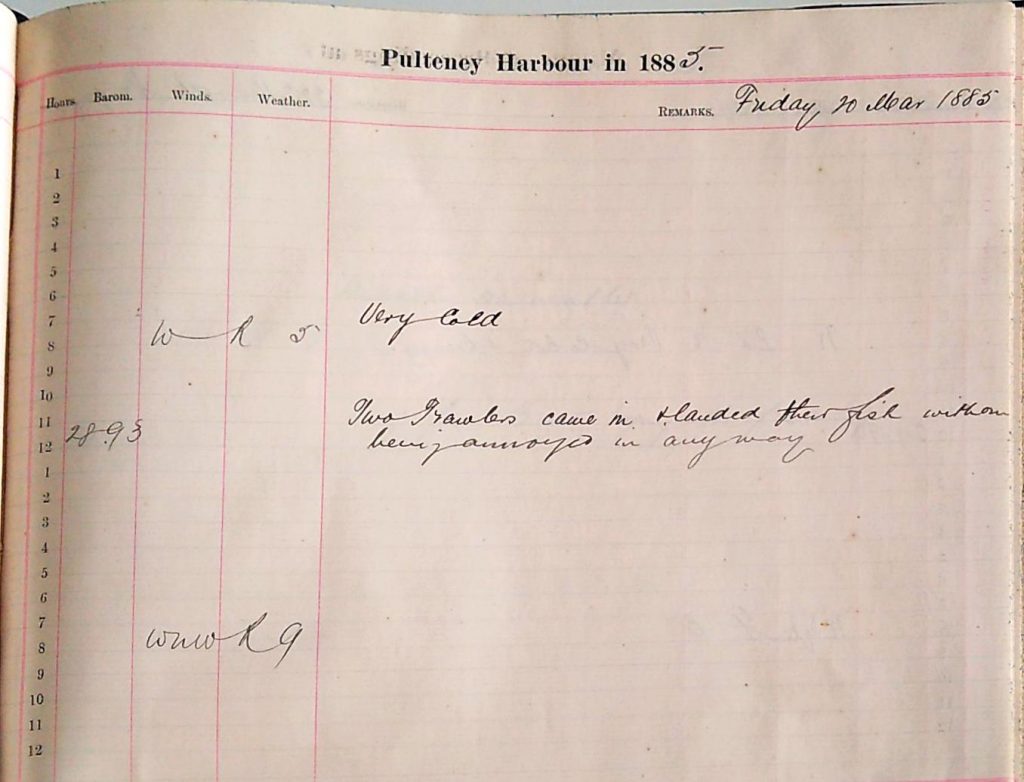

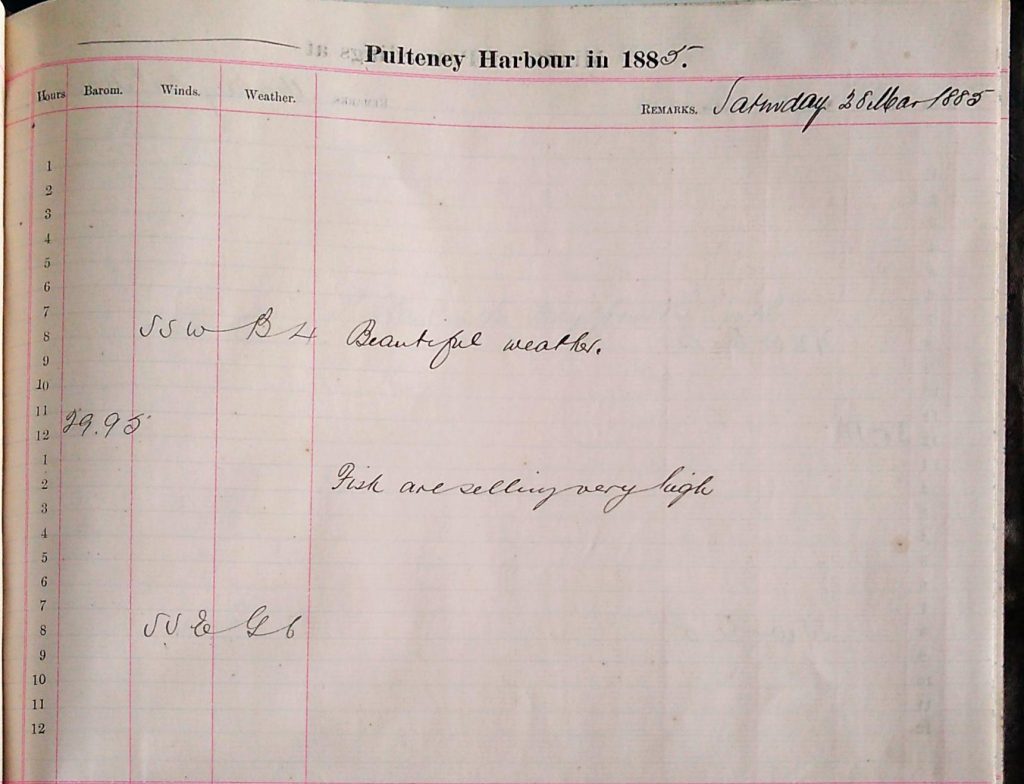

Tensions seem still to be high on the 17th when it is reported that ‘a trawler came to the bay today but according to orders Mr Payne told the Master not to attempt to come in for fear of a row. They dropped anchor in the bay’. A few days later however, on the 19th, ‘the “Palmerstone” steam trawler came in to sell her fish without any hostile show from our fishermen’ and again on the 20th two trawlers ‘landed their fish without being annoyed in any way’. It appears that the outcome is agreeable to the harbour master’s office and would of course make his running the harbour far less strenuous. Finally, by the 28th fish are again ‘selling very high’.

The efforts of the fisherman were not entirely in vain. Indeed, Sutherland tells us that ‘this incident went a long way to persuade interested parties that Aberdeen might be a better place to establish a base for the trawling industry’ and that by the end of the century the Court of Session had ruled that the Moray Firth should be closed to trawlers under the Herring Fisheries Act of 1889[28]. Also, by the end of 1885 Wick’s first trade union, the Worker’s Union, ‘was formed at a meeting in the Old Free Church at the end of the fishing season’[29].

Afterword

The breadth and depth of social, political and environmental history that the log books highlight is striking. Moreover, the often free and descriptive hand with which they are written makes the events more accessible and builds excitement and intrigue as we read. They are a valuable historical source and an insight into the functioning of the harbour master’s office, it’s responsibilities and influence, within the community. Presented here have been just a few weeks’ worth of entries that span nearly fifty years. There are, most certainly, a legion of stories still to be found within the log books and an afternoon passing through their pages is an absolute joy. We hope you have enjoyed these Stories from the Archive and will we be back with more very soon.

Read more Stories From The Archive

References

[1] Jean Dunlop, The British Fisheries Society 1786-1893 (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1978), p.187

[2] Ibid, p.191

[3] Ibid, p.192

[4] Joan Davies, ‘Rugged in the Extreme, Caithness Lifeboat Stations: Thurso and Wick’, The Lifeboat (Winter 1985/6), p.264

[5] Ibid.

[6]‘Slater’s Royal National Commercial Directory and Topography of Scotland, 1861’, Scottish Post Office Directories <https://digital.nls.uk/directories/browse/archive/91049075>[accessed 4th September 2020]

[7] ‘James Cormack’, The Grahams of Helensburgh <https://www.graham-clan.co.uk/thefamilytree/getperson.php?personID=I416&tree=tree1>[accessed 4th September 2020]

[8] Ibid.

[9] Dunlop, p.195

[10] Iain Sutherland, The War of the Orange, or the true story of Cogadh Mor Inbhir Uige (Wick Society, n.d.)

[11] Frank Foden, Wick of the North: The Story of a Scottish Royal Burgh (North of Scotland Newspapers, 1996), p.566

[12] Ibid, p.572

[13] J.J. Waterman, Measures, Stowage Rates and Yields of Fishery Products (Torry Research Station, 1979)

[14] Sutherland, The War of the Orange

[15] Foden, p.572

[16] Sutherland, The War of the Orange

[17] J. Mowat, James Bremner: Wreck Raiser (Wick, 1973)

[18] Iain Sutherland, The Fishing Industry of Caithness (Wick, c.2005), p.87

[19] Roland Paxton, ‘The Sea Versus Wick Breakwater 1863-77 – an instructive disaster’, Coasts, Marine Structures and Breakwaters: Adapting to Change (2010), p.32

[20] Ernest Mehew, ed., Selected Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson (Yale University Press, 1997), p.8

[21] Ibid

[22] Paxton, p.41

[23] Ibid, p.42

[24] Iain Sutherland, Herring to Seine Net Fishing on the East Coast of Scotland (Wick, Camps Bookshop, 1990), p.48

[25] Sutherland, The Fishing Industry of Caithness, p.131

[26] Ibid, p.132

[27] Iain Sutherland, Wick Harbour and the Herring Fishing (Wick, Camps Bookshop, n.d.), p.62

[28] Ibid

[29] Foden, p.501