On 16 September the Soviet defences around Kiev finally collapsed and the Germans took 500,000 prisoners. Two days later the city was in German hands and German soldiers began executing Soviet prisoners; some 350,000 Soviet soldiers were killed in the defence of Kiev. On 18 September Japanese officers were instructed to prepare their troops for operations in the Pacific.

There was unexpected joyful news for one Caithness family this week, when James Mowat of the Portland Arms Hotel in Lybster returned home after being reported missing in action over a year ago. James’s story is so remarkable, and highlights what so many families would have gone through during the war, that we are taking the unusual step of dedicating all this weeks’ Caithness at War to his memory.

James had been a member of the Supplementary Reserve (a territorial unit), and like many he was called up on 1 September 1939, two days before war was declared.

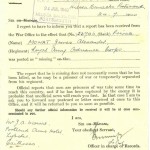

In January 1940 his unit was posted to northern France, but in the confusion of fighting when Germany invaded in May, and the retreat which led to the evacuation at Dunkirk, all trace of him was lost. In early June his father sent a letter hoping to reach him but the letter was sent back marked “addressee posted missing”.

In January 1940 his unit was posted to northern France, but in the confusion of fighting when Germany invaded in May, and the retreat which led to the evacuation at Dunkirk, all trace of him was lost. In early June his father sent a letter hoping to reach him but the letter was sent back marked “addressee posted missing”.

A month later the family received official notification that James had been posted as missing, but that this “does not necessarily mean that he has been killed”.

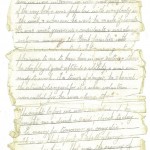

James’s corporal, H.E.T. Timms, who was now in a German prisoner of war camp, wrote to the family expressing his sympathy for their loss: Jimmy, as he called him, “was one of the best and popular with everyone in the Unit and wherever he went he made friends… The night before we were smashed up he bought me a drink saying Drink and be merry, tomorrow we may die.” It is in this spirit that I shall remember him.”

James’s corporal, H.E.T. Timms, who was now in a German prisoner of war camp, wrote to the family expressing his sympathy for their loss: Jimmy, as he called him, “was one of the best and popular with everyone in the Unit and wherever he went he made friends… The night before we were smashed up he bought me a drink saying Drink and be merry, tomorrow we may die.” It is in this spirit that I shall remember him.”

The family’s emotions at the news can only be imagined; for over a year they lived in the expectation that they would never see their son again. Then, out of the blue, they received a message from the American Red Cross that James was safe.

For it turned out that James had never been captured by the Germans in the summer of 1940. He’d formed a very good relationship with the French family he was billeted with, and this was what saved him. After the German breakthrough they managed to conceal him and arranged for his transfer to a safer farm that was not visited regularly by the German soldiers. (This family, Monsieur Havet and his daughter, were later arrested by the Gestapo on suspicion of helping Allied soldiers and airmen to escape and, as far as James knew, were never heard of again.)

With the aid of the French Resistance James and two friends escaped south into Spain where they were arrested and placed in a prison camp for ten days before being taken to Madrid; they were rescued from prison there by an official from the British Embassy. James reached Gibraltar on 3 September 1941.

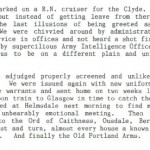

James’s own words in the account that he wrote of his adventures convey the relief and turmoil of emotions that he felt when his ordeal came to its end and he was finally home:

“Eventually we were adjudged properly screened and unlikely to be a threat to the War effort. We were issued again with new uniforms and unit badges, issued with railway warrants and sent home on two weeks leave. I was  able to catch an afternoon train to Glasgow in time to catch the night train north to home. I arrived at Helmsdale next morning to find my parents waiting. It was an almost unbearably emotional meeting. Then the last lap, the familiar road up to the Ord of Caithness, Ousdale, Berriedale, Dunbeath, Latheron, every twist and turn, almost every house a known family, all deeply etched in my memory. And finally the Old Portland Arms.”

able to catch an afternoon train to Glasgow in time to catch the night train north to home. I arrived at Helmsdale next morning to find my parents waiting. It was an almost unbearably emotional meeting. Then the last lap, the familiar road up to the Ord of Caithness, Ousdale, Berriedale, Dunbeath, Latheron, every twist and turn, almost every house a known family, all deeply etched in my memory. And finally the Old Portland Arms.”

James Mowat died in Lybster in 1951, still a young man, with his health apparently affected by his ordeal.