A Special Edition of Stories From The Archive

This edition of Stories From The Archive was researched and written by Dr Madison Marshall. Madison is a a White Rose scholar affiliated with the University of Leeds, though a permanent resident of Caithness. As part of her PhD study she undertook a one-month Researcher Employability Project (REP) at Nucleus: The Nuclear and Caithness Archives.

This blog is a result of that research and showcases Madison’s expertise in dialectology, the history of linguistics, and assembled album scholarship. We were delighted to welcome Madison to Nucleus and very lucky to gain such valuable insight into one of our collections.

A Brief Introduction

When you peel an egg, do you throw away the shells or the ‘scuttles’? Would you go for a ‘dander’ with your ‘brither-bairn’ on ‘Neever Day’? And when you last came to a ‘carrie-shangie’, were you in a fair ‘swither’? This edition of Stories From The Archive focusses on a fascinating hand-assembled album held in the Caithness Archives which features these and many other examples of Caithness dialect words and phrases.

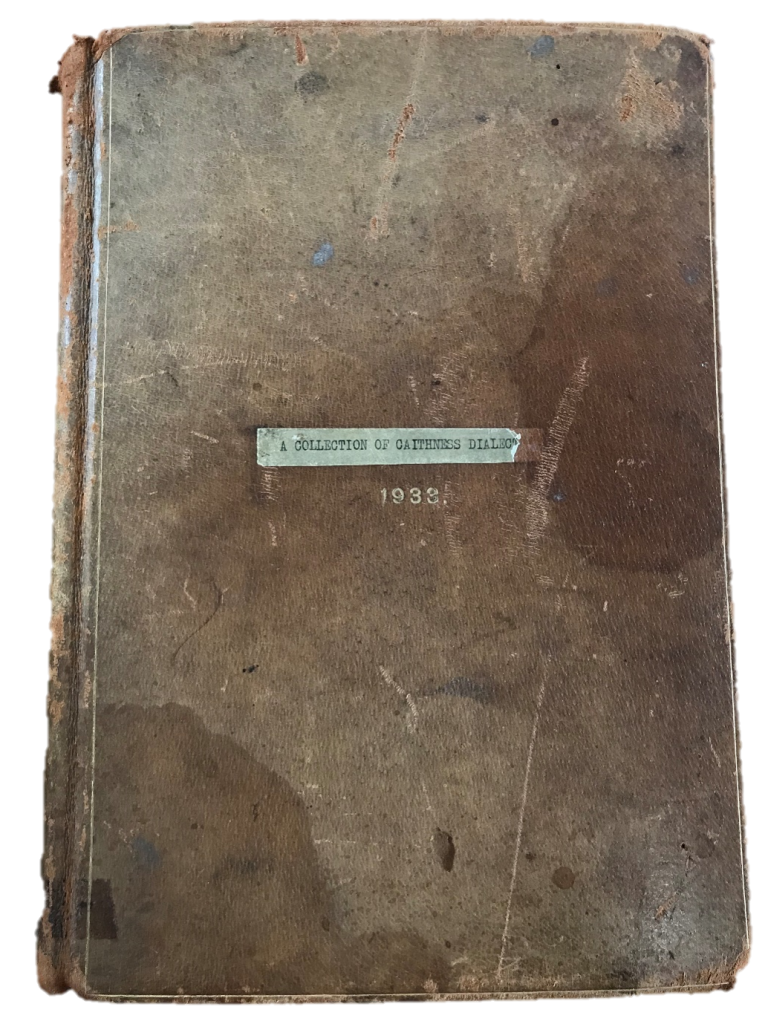

Compiled in 1933, A Collection of Caithness Dialect is a hand-assembled album containing newspaper cuttings from the Northern Ensign and the John O’Groat Journal columns ‘Talks on Topics. In the Caithness Doric’ and ‘ “Cracks” on Current Topics’. On the inside front cover is the first of two letters in the album from Canisbay-born schoolteacher David Nicolson (of Montpellier House in Wick) to the Rev. John Horne (Pastor of Springburn Baptist Church in Glasgow) concerning the latter’s dialect articles in the Northern Ensign.

Reflecting the contemporary tradition of collecting and remembering through material objects, the album emphasizes an enduring local pride in the Caithness dialect. It also highlights the tension between professional and amateur dialectologists in 19th- and 20th-century philological communities of practice.

Compiler

Although there is no information in the Caithness Archives to confirm who assembled A Collection of Caithness Dialect, the letters in the album addressed to John Horne (1861–1934) from David Nicolson (1834–1904) suggest that Horne was the compiler.

Contributors

The Rev. John Horne (‘H’), David Nicolson (‘D.B.N.’), John Mowat, the Rev. David Houston, William Bremner (‘Norseman’), William Coghill, Donald Doull (‘D.D.’), ‘Ancient’, ‘Philologist’, ‘Searcher’, and others.

Provenance: Private Collection

The Accessions Register at the Caithness Archives confirms that this artefact was received along with other archive collections from Wick Library in 1995.

Format: Hand-assembled album, bound in brown full-leather

In the expanding field of assembled album scholarship, there is some disagreement about the grouping and labelling of album genres. Variously categorized as commonplace books, scrapbooks, and autograph, friendship or sentiment albums, all of these artefacts begin as (often manufactured for purpose) blank-leaved books whose pages are filled with miscellanea by one or more compilers.

Despite the lack of consensus among album scholars, it is generally accepted that the Renaissance practice of assembling commonplace books and the 19th-century tradition of compiling scrapbooks reflect the consciousness of an individual assembler, while the albums that derive from the 16th-century German tradition of Album Amicorum (‘family’ or ‘friendship’ books), also called Stammbücher, represent the shared communities of the (often many) hands that contribute to their production.[1]

Designed to preserve the Caithness dialect and influence an audience in futurity, A Collection of Caithness Dialect in some ways illustrates the practices of commonplacing (it is self-assembled and reveals aspects of the assembler’s interests) and scrapping (the materials are self-selected, arranged more or less chronologically, and pasted using basic scrapping techniques).

However, while it is likely that the Caithness Dialect album was assembled by one hand, many hands produced the dialect contributions in the newspaper clippings. Consequently, the album contents represent the shared communities of practice whose common goal was to identify, categorize and preserve Caithness dialect words and phrases. In this context, the album also sits on the taxonomic periphery of the multi-handed Album Amicorum.

Notes on the Compiler

The Rev. John Horne was ‘so indubitably Caithness that he may be described as bi-lingual’[2]

Born on 10 May 1861 at 12 Louisburgh Street in Wick, John Horne trained as an apprentice printer after leaving school and worked for eight years as a compositor for the Northern Ensign and Weekly Gazette (a Wick-based newspaper published between 1854 and 1926 for the Counties of Caithness, Ross, Sutherland, Orkney and Shetland).[4]

Horne subsequently trained at the Rev. Charles Spurgeon’s College in London and in 1866 became the first minister of the Baptist Church in Ayr. Horne later transferred to Springburn Baptist Church in Glasgow before moving on to the Baptist Church in Kirkintilloch.[5] He married Margaret Morrison (1866–1949) on 6 June 1889 and died at their home at Norland, Longbank Road in Ayr on 10 November 1934. Horne’s ashes were returned to Wick and buried in the resting place of his parents, Donald Horne (1826–1891) and Jane Taylor (1832–1908), at the Old Municipal Cemetery.[6]

Although Horne’s calling as a minister displaced him from his beloved homeland, he remained passionate about the Caithness landscape, its dialect, and its people. A celebrated writer of poems and books about the county of Caithness, Horne disclosed with characteristic modesty how he ‘unwittingly became a sort of symbol or representative of the old home and the sentiments associated with it’.[7] ‘When I began writing about Caithness’, he revealed, ‘there was no one else doing it’.[8]

In appreciation of Horne’s ‘influence in fostering love and loyalty to the Homeland’, a bed was named in his honour on Wednesday 20 July 1932 at the former Bignold Hospital on George Street.[9] And more recently, John Horne Drive in Wick was named in recognition of this revered Caithnessian’s exemplary contribution to the local community.

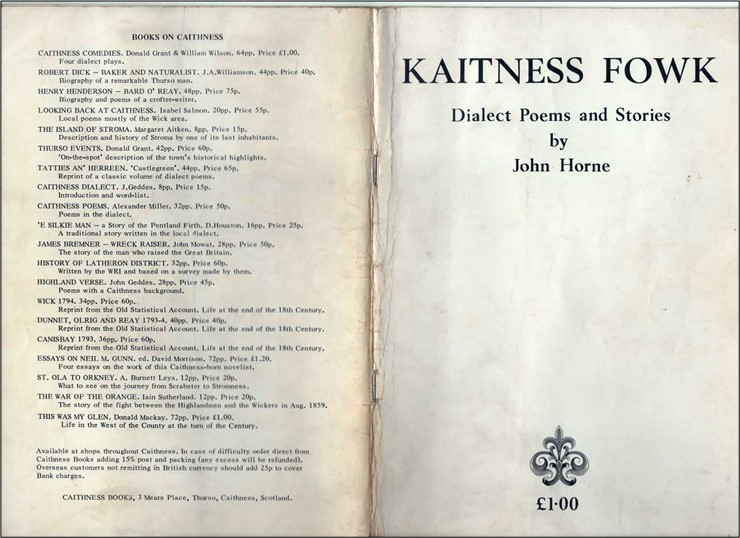

Horne’s celebrated works include Kaitness Fowk: Dialect Stories and Poems,[10] A Canny Countryside,[11] and his ‘handsomely printed little Note-book’, Wick: In and Around It.[12] An amateur dialectologist, Horne made numerous dialect contributions to the Ensign and the John O’Groat Journal, many of which appear in the featured assembled album under the initial ‘H’.

Traditional Dialectology

Pride comes before a fall

Our fascination with the accents and dialects of the British Isles is a feature of modern life, but people have long been interested in questions such as what names we give to bread in different regions or how we pronounce words like ‘scone’ and ‘bath’. Whether we favour ‘bap’, ‘barm cake’ or ‘morning roll’, or we pronounce ‘scone’ to rhyme with ‘boon’, ‘gone’, or ‘bone’, we often take local pride in the way we speak.

However, language is continually being reshaped by its users. New words are coined. Others fall out of usage, and the pronunciation and meanings of existing words change over time. Traditional dialectology seeks to record regional language use at a given point in time (synchronic variation) and chronicle its development through history (diachronic variation).

A linguistic battle

Dialectology lost currency in the 20th century as it jostled for academic hegemony with the emergent field of linguistics (the scientific study of language) and its sub-discipline sociolinguistics (the study of how language use interacts with, or is affected by, social factors such as age, gender, race or class).

Revitalized by recent technological and methodological advances, however, dialectology plays an important role in the study of language in the 21st century and maintains its primary purpose to chronicle the dialect (vocabulary), accent (pronunciation), and grammatical features associated with particular regional or social groups.

Early approaches to dialect studies

As an academic field, dialectology had its effective beginnings in the 19th century when the compilation of etymological dictionaries and grammars became popular in Western Europe. Its earliest practitioners followed in the footsteps of generations of amateur antiquarians whose chief interest was the preservation of rural forms ‘uncontaminated’ by contact with urban speech communities.[13]

These early studies were often undertaken by enthusiasts describing or recording the dialect of their birthplace (a practice exemplified by John Horne), and by veteran hobbyists of philology (such as David Nicolson) or trained fieldworkers (ethnographers) who interacted with speakers of the dialect. Although these studies focussed on lexis (vocabulary), subsequent work began to look at the differences in pronunciation and grammar associated with the dialect.

The dialect map

From this work emerged a number of large-scale geographical dialect surveys, led by Joseph Wright’s English Dialect Dictionary.[14] These ambitious surveys gave rise to the dialect map (or linguistic atlas). Partly fulfilling their aim to depict the distribution of dialect words and pronunciations into regions, these maps were (and are) useful visual aids, though there is often considerable discrepancy between the early dialect maps and present administrative partitions.[15]

Dialectologists continued to produce linguistic atlases in the 20th century, and dialect maps often appear in today’s popular press for illustrative purposes. However, there are disadvantages to using this visual geolinguistic approach.

The anecdotal dialect map below, for example, implies that different words for bread can be tightly located within regional boundaries, but this is not the case. There is often more than one word used to describe types of bread in the same region. Anyone from Caithness will know that there is a difference between a ‘Scotch morning roll’ and a ‘softie’, both of which can be bought locally.

There are also social factors to consider such as age, background and social movement. As someone who has lived and worked in many parts of the UK, for instance, I have variously used the terms ‘bread-cake’, ‘bread roll’, and ‘cob’.

The main issue, however, is that there are no clearly defined mergers and splits to differentiate usage between neighbouring dialects or those further afield.

Roll, Rowie or Bap?

What’s a word or two between districts?

By way of illustration, let’s say you’ve decided to walk or cycle from John O’Groats to Land’s End. Consider how many different accents and dialects you would hear as you stopped along the way. How far away from Groats would you travel before coming across a spoken variety that you found difficult to understand?

The answer is likely some distance, and certainly way beyond Caithness because there are no distinct breaks between one accent and dialect and a geographically adjacent variety. This is why speakers in neighbouring and nearby places can easily understand one another. Linguists refer to this as a dialect continuum or chain of mutual intelligibility.

There is, however, a cumulative effect of accent and dialect differences. Put simply, the greater the geographical separation, the greater the difficulty we have in understanding what people say.[18] For example, a ‘Groater’ can easily converse with a ‘Wicker’ (from the nearby Highland town of Wick), but she or he might not as readily converse with a native Cornish speaker.

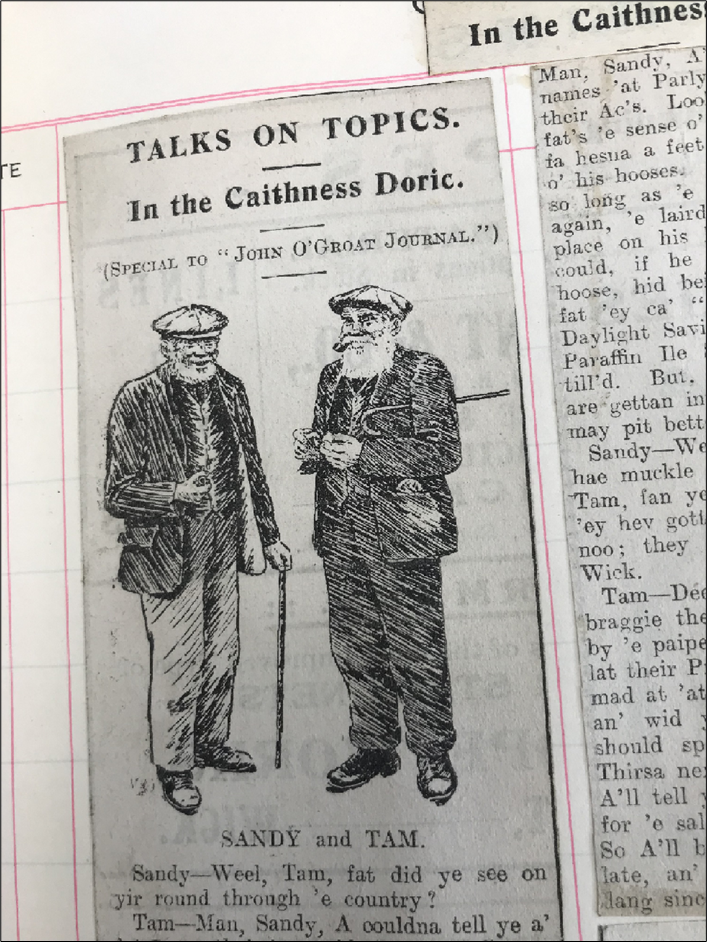

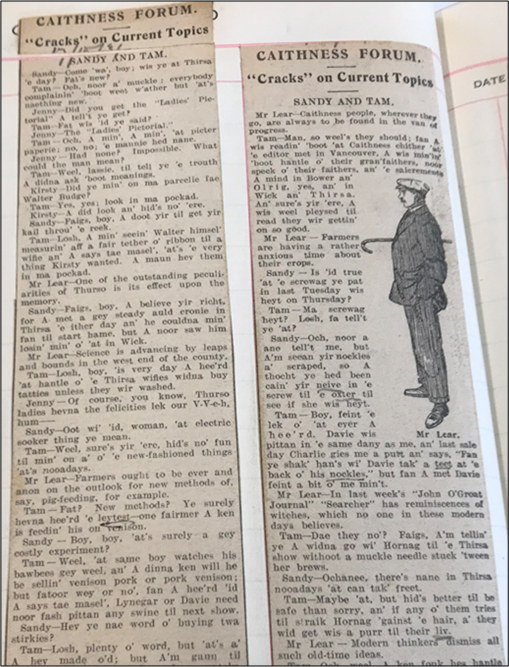

Likewise, if we take as an example the dialect used by the fictional characters Sandy and Tam in the long-running John O’Groat Journal series ‘Talks on Topics’ and ‘ “Cracks” on Current Topics’, we might ask how much of their dialect a Cornish speaker would understand.

Clipping from the John O’Groat Journal newspaper column ‘Talks on Topics. In the Caithness Doric’, which features the characters Sandy and Tam – A Collection of Caithness Dialect 1933 (Ref. P130)

As the clipping below from the Caithness Dialect album shows, the dialogue between Sandy and Tam was written in such a way as to represent both the accent and dialect of Caithness. Their vernacular is offset by the character Mr Lear whose use of Standard English and perspectives on local issues suggest he is an incomer (someone who lives in Caithness having relocated from elsewhere). At first glance, an incomer or visitor to Caithness might struggle to follow the conversation.

Clipping from ‘ “Cracks” on Current Topics’ in the John O’Groat Journal featuring the characters Sandy and Tam in conversation with Mr Lear — A Collection of Caithness Dialect 1933 (Ref. P130)

Professional vs amateur

Aside from the dialect continuum muddying the regional waters, a further problem encountered by early dialectologists was the tension between ‘professional’ and ‘amateur’ practitioners in philological communities of practice.

In the last half of the 19th century and first half of the 20th, an increasingly sharp distinction was drawn between those who made the study of language(s) their life’s work and those who made a pastime of recording or commenting on their own dialects. There were main two points of contention.

First, speakers have propositional and practical knowledge of their own dialect, but this does not necessarily mean they can analyse the syntactic structure of sentences or describe in linguistic terms the phonological features of their variety (phonology is the branch of linguistics that studies how languages or dialects systematically organize their speech sounds).

Second, many amateur dialectologists writing at the time of John Horne and David Nicolson focussed on their own dialects, and they were not always ideally placed to draw comparisons with varieties used in other regions.

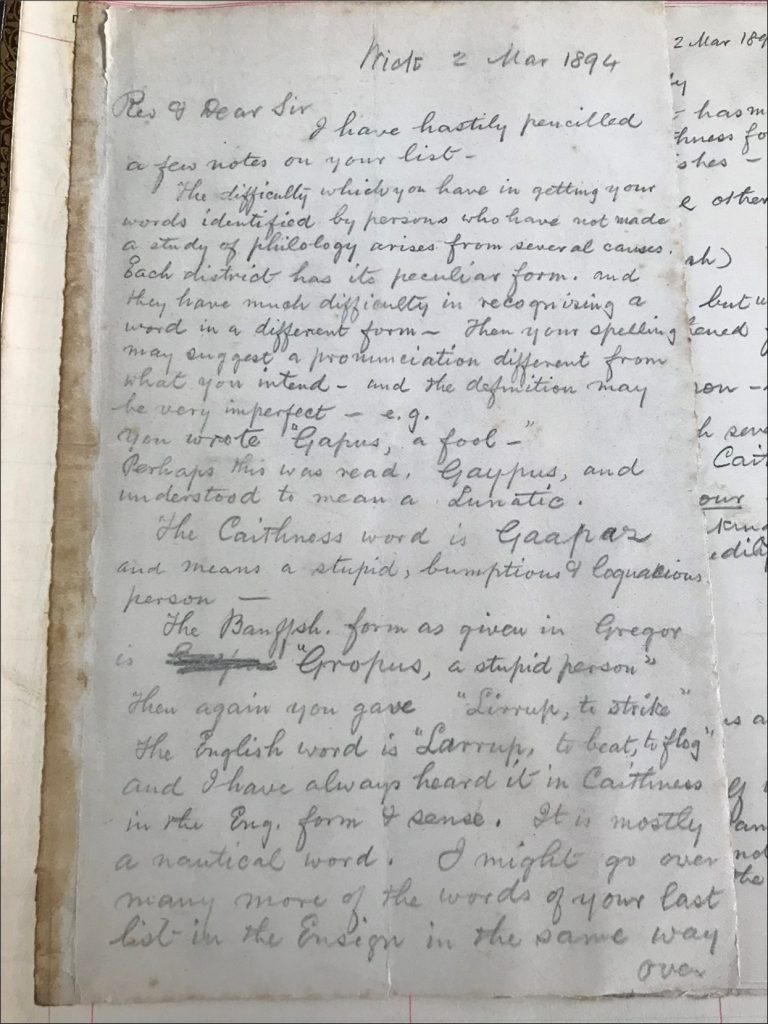

This position is neatly summed up in the opening of Nicolson’s letter, dated 2 March 1894, to his former pupil Horne. The letter’s significance is emphasized by its place of prominence on the inside front cover of the Caithness Dialect album. Referring to Horne’s ‘last list’ of Wick dialect words in the Ensign, Nicolson writes:

‘The difficulty which you have in getting your words identified by persons who have not made a study of philology arises from several causes’.

One of these ‘causes’, explains Nicolson, is the dialect speaker’s ‘difficulty in recognising a word in a different form’. Suggesting that some of Horne’s spellings indicate pronunciations he did not intend, Nicolson cites Horne’s ‘Gapus, a fool’ as one of his many ‘very imperfect’ definitions.

Guide to transcriptions

Phonetic transcription is placed between square brackets [ ]

- Phonetic (or ‘narrow’) transcription uses symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) to represent actual speech sounds in terms of their acoustic and articulatory properties.

Phonemic transcription is placed between slashes / /

- Phonemic (or ‘broad’) transcription represents the realization of a phoneme (speech sound) and gives an abstract indication of pronunciation.

Orthographic transcription is placed between angled brackets < >

- Orthographic transcription represents the standard and/or dialect spelling.

Horne’s ‘Gapus’ corresponds with the entry in Jamieson’s Supplement to the Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language, which cites the Scots form as ‘GILLIE-GAPUS, s. A fool’.[19] However, Nicolson contends that this is not the form used in Caithness.

Quoting Walter Gregor’s 1866 Dialect of Banffshire—which defines the obsolete (indicated by †) Bnff. form as ‘Gropus, n. A stupid person, a fool’[20]—Nicolson cites the Caithness form in his letter to Horne as ‘Gaapas’, meaning ‘a stupid, bumptious & loquacious person’.

The subsequent entry ‘GAWPUS, GAUPUS’ in the Scottish National Dictionary (SND) identifies two pronunciations. The first is /gɑ(:)pəs/, with the open back unrounded vowel (represented by the IPA symbol [ɑ], as in ‘car’), and the second (designated a Caithness pronunciation) is given as /’ge:pəs/, with a close mid-front unrounded vowel (represented by the IPA symbol [e], as in ‘pay’).[21]

It is entirely possible, however, that Nicolson’s spelling offers an alternative Caithness pronunciation. Although some writers used <aa> instead of <aw> and <au> when writing Northern and Insular Scots,[22] the <aa> spelling was also used to indicate the open front unrounded vowel (represented by the IPA symbol [a], as in snaw ‘snow’).[23]

We know that Nicolson favoured the use of phonemic orthography—which is the practice of writing graphemes (letters) to correspond with the phonemes (sounds) of a word—because he gently reproached Horne for using spellings that signposted an unintended or inaccurate pronunciation. Nicolson’s <aa> spelling in gaapas could, therefore, suggest that the Caithness form he recorded at the time replaced the [e] vowel phoneme in /’ge:pəs/, with the [a] in /’gapəs/.

When we are relying on phonemic orthography to give us an idea of how a word sounded, the pronunciation is not always clear from the graphemes used to represent the underlying phonemes. Nevertheless, the available records seem to support Nicolson’s assertion that the form gaapas was restricted to Caithness.

First page of a handwritten letter from David Nicolson to John Horne dated Friday 2 March 1894 — A Collection of Caithness Dialect 1933 (Ref. P130)

Although Nicolson corrected what he saw as Horne’s imprecisions, his letter illustrates the contemporary division between those who might reasonably be awarded the epithet ‘philologist’ and those who were deemed ‘enthusiasts’. Nicolson was a self-styled philological hobbyist, but his personal knowledge of the Caithness dialect was supplemented by 35 years of philological pursuits.

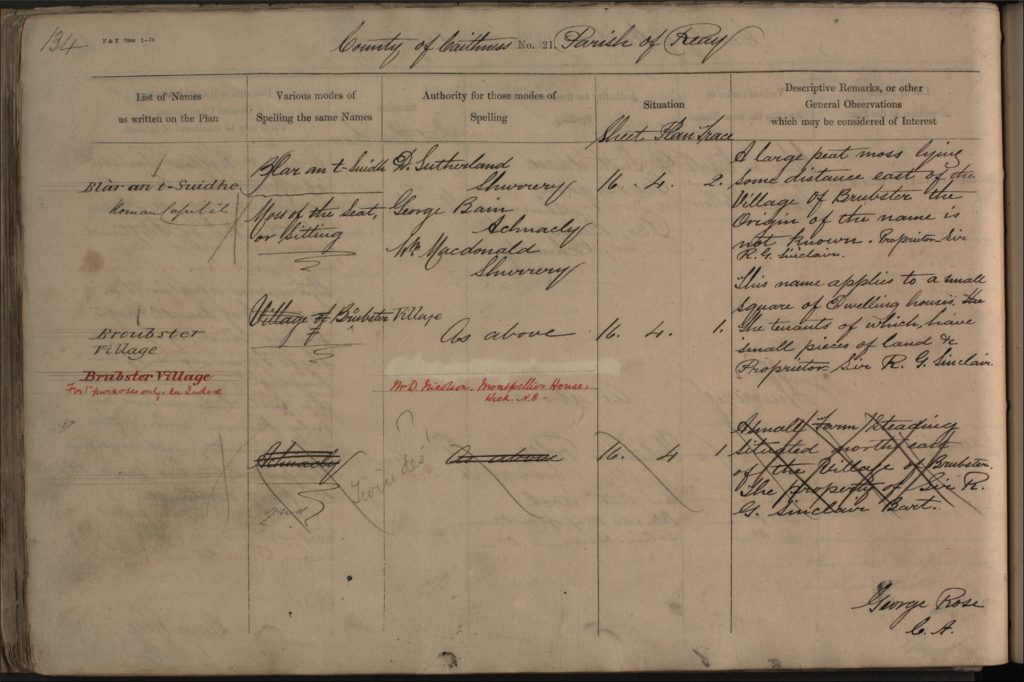

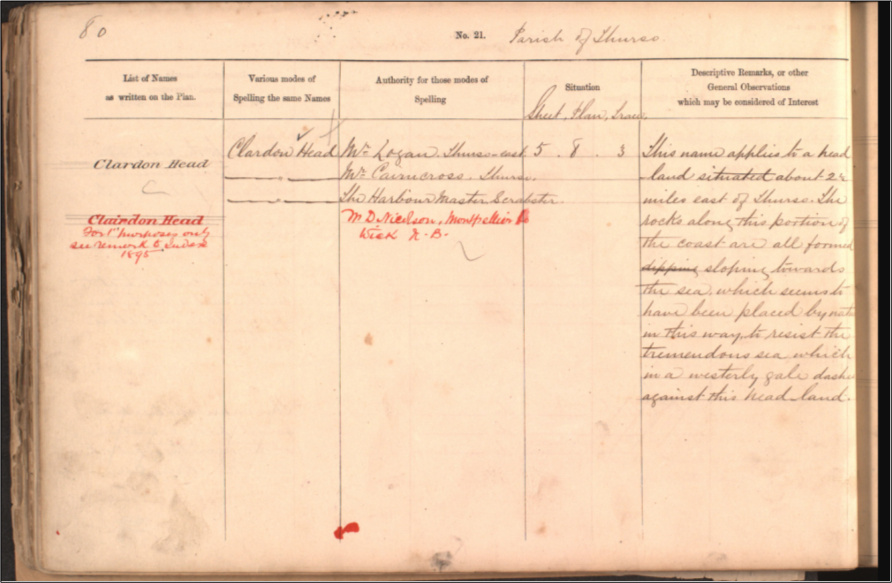

He was well known in and beyond Wick for his dialect word lists, and his contributions to Northern Scottish philology assumed many forms. The entries for Nicolson’s spellings of ‘Brubster Village’ and ‘Clairdon Head’ in the Caithness Ordnance Survey Name Books below indicate that he was considered an authority voice by many (see entries highlighted in red).

Caithness Ordnance Survey Name Books, 1871–1873, Caithness volume 09, Parish of Reay (scotlandsplaces.gov.uk – OS1/7/9/134)

Caithness Ordnance Survey Name Books, 1871–1873, Caithness volume 11, Parish of Thurso (scotlandsplaces.gov.uk – OS1/7/11/80)

The backlash that came from readers who had seen Horne’s ‘Wick Words’ in the Ensign was largely unsympathetic. However, some of the newspaper clippings in the Caithness Dialect album demonstrate that while Horne responded to his critics with characteristic humility, he also forcefully defended his position.

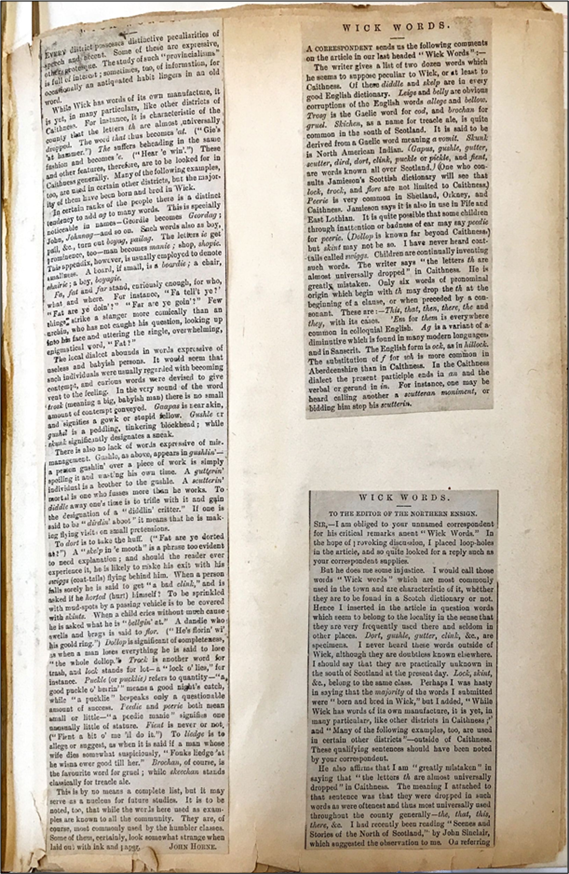

The first clipping below (left column) is an extract from Horne’s ‘Wick Words’. The second (top right column) is a newspaper correspondent’s criticism of Horne’s list, and the third (bottom right) is Horne’s reply. Addressing the Editor of the Ensign, Horne writes:

‘Perhaps I was hasty in saying that the majority of the words I submitted were “born and bred in Wick,” but I added, “While Wick has words of its own manufacture, it is yet, in many particulars, like other districts in Caithness;” and “Many of the following examples, too, are used in certain other districts”—outside of Caithness. These qualifying sentences should have been noted by your correspondent’.

In the correspondent’s zeal to criticize, he failed to observe some of the detail and implied meanings in Horne’s list. For example, Horne alludes to the Caithnessian ellipsis of the initial consonant cluster <th>, represented by the IPA symbol [ð]. It is ‘characteristic of the county’, he writes, ‘that the letters th are almost universally dropped’. Horne is referring to the omission of [ð] in determiners such as the (‘ee’), this (‘is’) and that (‘at’), but the Ensign correspondent misunderstands Horne to mean all words beginning with <th>.

We can see numerous examples of this ellipsis in the conversations between the fictional characters Sandy and Tam in the John O’Groat Journal, which suggests that this phonological feature was widespread at the time. And anyone who lives or has spent time in Caithness will be aware that this ellipsis remains a feature of the dialect today.

What is interesting in terms of current usage is that the phoneme [ð] is often elided and articulated within the same sentence. I have documented numerous recent cases where the ellipsis occurs in the main clause but not the subordinate clause, and vice-versa (as, for example, in the main clause, “I forgot to bring ‘ee’ letters”, and the subordinate clause, “so I’ll get the stamps next time”).

Clippings on the subject of John Horne’s ‘Wick Words’ from the Ensign — A Collection of Caithness Dialect 1933 (Ref. P130)

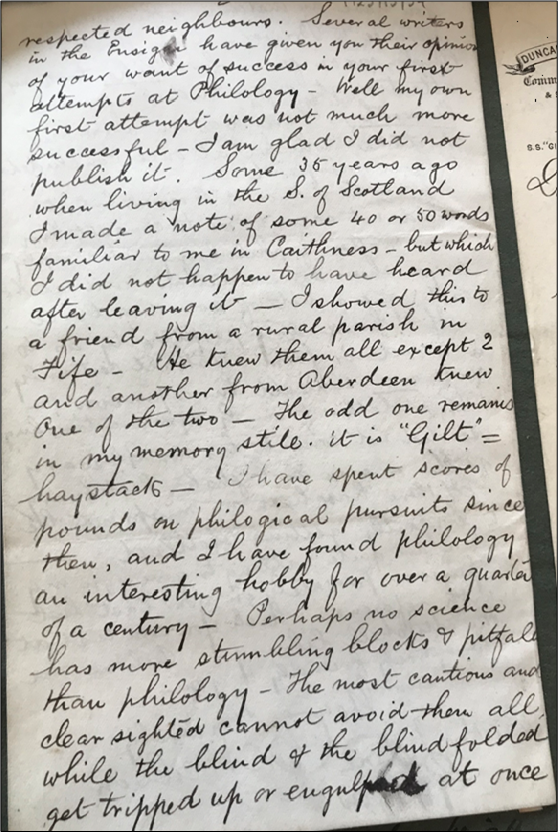

Nicolson held a position of philological seniority over Horne, but he chose to distance himself from the hostile reader response to ‘Wick Words’. This is evident from Nicolson’s first letter to Horne composed on 22 February 1894, which is held in a separate album of multi-handed correspondence in the Caithness Archives (Ref. P125/15/5). Offering the sort of encouraging advice that a teacher might offer an attentive pupil, and admitting his own first attempt at philology was ‘not much more successful’ than Horne’s, Nicolson writes:

‘Some 35 years ago when living in the S[outh] of Scotland I made a note of some 40 or 50 words familiar to me in Caithness – but which I did not happen to have heard after leaving it – I showed this to a friend from a rural parish in Fife – He knew them all except 2 and another from Aberdeen knew one of the two’

Nicolson shared this anecdote to reassure Horne that he was not the first to fall prey to the ‘stumbling blocks’ of philology. By assuming that the words on his lists were indigenous to Caithness and used exclusively in the county, Horne (like Nicolson 35 years before him) floundered at the first dialectological hurdle. He was unaware that many of the words on his list were prevalent in other districts.

This was a common pitfall. Indeed, some of Nicolson’s own ‘stumbling blocks’ were subsequently pointed out by James Mather, co-editor of the Linguistic Atlas of Scotland.[24] Challenging Nicolson’s claim that all the dialect forms he had personally listed were ‘peculiar to the North’,[25] Mather observed that many of Nicolson’s words were (or are) ‘known throughout Scotland–or at least in many other places than ‘the North’ ’.[26]

Second page of a handwritten letter from David Nicolson to John Horne dated 22 February 1894 (Ref. P125/15/5)

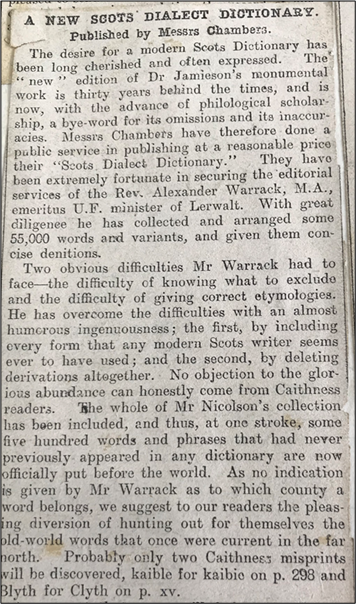

Five hundred of Nicolson’s words and phrases are included in the 1911 revised edition of Chambers Scots Dictionary.[27] Sadly, Nicolson did not live to enjoy this recognition. But he was remembered for his dialect work in the home county long after his death.

Naming Nicolson as an important contributor, the John O’Groat Journal issued a press release for the ‘New Scots Dialect Dictionary’ by ‘Messrs Chambers’. Horne meanwhile paid tribute to his former teacher by including the Groat press release in his Caithness Dialect album.

Press release for Chambers Scottish Dictionary in the John O’Groat Journal, cut and pasted into A Collection of Caithness Dialect 1933 (Ref. P130)

Linguistic Background

What does the past give to the present?

Examining past ideas about language in a modern academic context comes under a branch of linguistics known as the history of linguistics. Historians of linguistics are ‘observers’, ‘critical readers’, and ‘interpreters’ of the evolutionary course of linguistic knowledge.[28] What this means is that we look at how our linguistic predecessors studied the origin and development of language(s) in the context of their own time. From the outset, this requires a basic attitude of empathy with the past.

It is essential to bear in mind, however, that just as language changes over time, so does our approach to studying it. While the work of people like Nicolson represents a noteworthy contribution to Northern Scots dialectology, new research continues to build on previous work and often supports alternative readings of earlier findings.

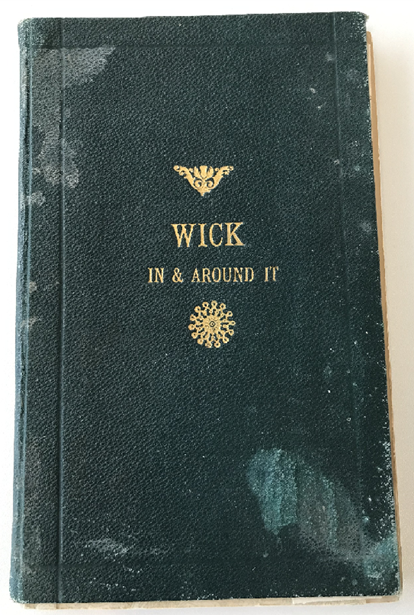

Let us consider as an example John Mowat’s The Place=Names of Canisbay, published in 1931. Mowat acknowledges Nicolson’s ‘valuable contribution’ to Caithness toponymy (the study of place-names). However, he also observes that Nicolson’s list of toponyms is ‘more suggestive and illustrative than exhaustive’,[29] and he admits that Nicolson’s derivations cited in Place=Names have been revised by A. W. Johnston (a president of the Viking Society for Northern Research, est. in 1892 as the Orkney, Shetland and Northern Society).[30]

This is not to denigrate Nicolson’s or anyone else’s work, but to seek answers based on available and newly uncovered evidence. As Professor Michael Barnes (Honorary Research Fellow at UHI’s Institute for Northern Studies) observes in his paper on the Norse philologist Jakob Jakobsen, the ‘greatest service’ we can offer our linguistic forebears is to assess their work with a critical eye, because only by doing this can we fully understand the significance of their contributions and identify areas for further study.[31]

The problem of borrowings

While the history of linguistics looks at the ways in which language has been studied from antiquity to the present, historical linguistics is concerned with phonological, grammatical and semantic changes in language itself. Historical linguists apply various comparative methods to demonstrate genetic relationships among languages. One of the many processes they observe is the transfer of words (often with some modification) from one language to another. This process is known as lexical borrowing.

We know that these borrowings (also known as loanwords, though they are not returned) are the result of population contact, but we do not always know the precise circumstances of the contact and the nature of its effects.[32] Linguistic evidence suggests that the Norse settlements resulted in several borrowings from Norwegian into Scots,[33] for example, but it is not always clear which forms were borrowed during the Viking Age from Old Norse (the language of Norway c. 750 to c. 1350, and of Iceland c. 870 to c. 1550),[34] and which were borrowed from other Scandinavian and North Sea languages beyond the end of the Middle Ages.[35]

The trade contacts across the North Sea and immigration from the east side of the North Sea to Scotland resulted in many borrowings into Scots, but these sources have been difficult to identify precisely because they could derive from Low German directly, or from Low German via the Scandinavian languages (due to the economic and cultural contact between northern Germany and the Scandinavian countries in the medieval period).[36]

We must also consider the influence of the Norn language, which is a (now extinct) type of Old Scandinavian or Old Norse that was brought to Orkney and Shetland by the Viking invaders (the term ‘Norn’ derives from the Old Norse adjective norrœnn, ‘Norwegian, Norse’, and/or the corresponding noun norrœna, ‘Norwegian language, Norse language’).[37]

Some commentators have wanted to include Caithness under the geographical confines of Norn.[38] This is because the county had links with the Norse Earldom of Orkney,[39] and the proximity of Orkney and Shetland to the northern Scottish mainland facilitated both immigration and linguistic contact between Caithness and the Northern Isles.

The Norse scholar Per Thorsen estimated that a few hundred Norn words were borrowed into the Caithness dialect and mainland Scots more generally, including brither-bairn, which he suggests derives from the Norn plural form brœðraborn.[40] However, as discussed below in ‘Examples from the Caithness Dialect album’, this compound noun is also attested in Old English c. 1000.

It has many cognates (words in different languages that come from the same word of origin) in other Germanic languages, and could have been borrowed into Scots via a number of Germanic channels of contact or influence. It is also important to point out that many current authorities apply the term Norn ‘almost exclusively to refer to Scandinavian speech as it developed in Orkney and Shetland’.[41]

Despite the uncertainty surrounding some of the circumstances that have led to lexical borrowing into Scots from other languages, we know that the Scandinavian languages and Scots share a common origin. As the Indo-European (IE) language family tree below illustrates, Scots and its sister language English belong to the West branch of the Germanic family of languages, while the Scandinavian languages (and Norn) belong to the North Germanic branch.

The Caithness dialect situation is further complicated by Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig), which derives from the q-Celtic (Goidelic/Gaelic) branch of the northern group of Celtic languages in the IE family tree (shown below).

Alhough Gaelic ‘has never been (or reportedly has never been) spoken to a considerable extent’ east of a line drawn from Thurso (Baile Theòrsa) to Wick (Inbhir Uige),[44] census enumerations from 1881 to 1931 show that at the time David Nicolson and John Horne were writing about the dialect of Caithness (Gallaibh), Gaelic was still spoken by a small percentage of inhabitants, though its use declined during the half-century between the return of these two censuses.

![Gàidhlig (Gaelic) speakers by age and birthplace — Census 1891 returns from enumeration divisions in the civil parish of Latharan (Latheron)[45]](https://www.highlifehighland.com/nucleus-nuclear-caithness-archives/wp-content/uploads/sites/121/2023/01/Picture17.png)

Gàidhlig (Gaelic) speakers by age and birthplace — Census 1891 returns from enumeration divisions in the civil parish of Latharan (Latheron)[45]

Almost all recorded Gaelic speakers in the county were born before 1891, which means that the intergenerational transmission of the language had effectively already ceased.[46] Consequently, the Registrar General of the 1911 Census concluded that the language was no longer in ‘habitual use’ in Caithness.[47]

However, Gaelic left a legacy. A recent study based on the dialect materials composed and collected by the Wick-born local historian Iain Sutherland (held at the Caithness Archives) suggests that the linguistic interaction between the Scots and Gaelic populations in Caithness steered several instances of borrowing from Gaelic into the Caithness dialect.[48]

This is not to deny the strong Norse tradition in Caithness. Bearing testimony to the profound Scandinavian influence on the language communities of Northern Scotland during the Viking Age, the influence of raiders and settlers from the Nordic countries is evidenced by the many toponyms of Norse origin in the Highlands and Islands.

Although the limitations of toponymic material is now well-documented,[49] and there are place-names of Gaelic origin in these areas as well as Norse, the Scandinavian (and, therefore, Germanic) influence on northern Scots dialects can still be traced in everyday usage, as some examples below from the Caithness Dialect album illustrate.

Examples from the Caithness Dialect album

We warmly encourage you to visit the Caithness Archives to consult the featured album and other material objects and documents pertaining to the Caithness dialect. You may be interested in Aneas Bayne’s 1753 Short Geographical Survey of the County of Caithness (Ref. P793) and his accompanying notes (Ref. P189), for example, or the dialect word lists and sound recordings that form part of the Iain Sutherland Collection (Ref. P/SUTH). It all makes for stimulating reading and listening.

To whet your appetite in the meantime, below are some examples of dialect words and phrases from the newspaper clippings that appear in the Caithness Dialect album. While the words in the album do not necessarily constitute a set of linguistic forms exclusively restricted to Caithness, they do give us some insight into the variants that were either used in this area at the time or were remembered by Caithnessians as being used historically.

Brither-bairn—n. Cousin. Similarly, brither-dochter—niece; brither-sin—nephew

The following anecdote—which also appears in Nicolson’s ‘Dialect’[50]—is cited in the newspaper clipping that includes the definition of brither-bairn, –dochter, -sin:

‘A Stroma man, a witness in a trial for breaching of the peace gave the following classical evidence:—“Shirra, ma lord, ‘iss is ‘e wy’d began ‘e wy’d began wiz iss. First ‘er wiz a sma’ tit tat, ‘en ‘ey cam tae a curryshang (uproar), a’fore ye’d kiss’d yer ain —— twice, ‘ey wir in ae carrywattle on my brither-sin’s shillin’ hillag” ’

The same definition of brither-bairn is recorded for Caithness in the 1905 Supplement of Joseph Wright’s English Dialect Dictionary:

‘(1) brither-bairn, cousin; (2) brither-dochter, “a niece” (Cai. 1905 E.D.D. Suppl.)’[51]

And the SND records an oral source from 1936, which assigns to brither-bairn the meaning of ‘uncle’s son‘;[52] ‘uncle’s son’ is, of course, another way to state a cousin relationship (see also Iain Sutherland’s Caithness Dictionary, which gives the meaning as ‘cousin’)[53]:

‘He’s ma brither-bairn [i.e. uncle’s son], bit a’ll no heyl [spare] ‘im’[54]

The first element of the compound noun brither-bairn is Germanic in origin and derives from ‘brother’.[55] Recorded both in Old English (bróðer, -or, breðer) and Old Norse (bróðer, -ir), ‘brother’ has numerous cognates, including Old Frisian brōther, brōder, Old Icelandic bróðir, Old Swedish brōþir, and Old Danish brōthær.[56] Chronicled in Scots after 1700, the form brither was also prevalent in south-western and northern English in the 1800s.

N.B. Traditionally, the history of the English language is divided into four periods:

-

Old English (OE) – c.450 AD to c.1150

-

Middle English (ME) – c.1150 to c.1450

-

Early Modern English (EMnE) – c.1450 to c.1800

-

Late Modern English (MnE) (also Present-Day English) (PDE) – c.1800 to present

The pronunciation of the stressed vowel in MnE ‘brother’ results from the shortening of ME long close ō (sounds like MnE [o], as in ‘boat’) to ŭ (sounds like MnE [u], as in ‘boot’). However, when Nicolson and Horne were documenting the Caithness dialect, the stem vowel in ‘brother’ may have been articulated in a raised position, with the tongue positioned closer to the roof of the mouth.

Although the spelling variant <i> in brither indicates the pronunciation [ɪ] (to rhyme with ‘dither’), the SND records a pronunciation for North-East Scotland of [i] (to rhyme with ‘breather’).[57] (Compare with north-eastern Scots breether, recorded in the 1800s.)[58]

This suggests that the stem vowel in ‘brother’ was fronted to [i] when its usage was logged by Nicolson, Horne and other writers on the Caithness dialect. (Fronting occurs when there is a shift in the place of articulation of a vowel to the highest point of the tongue during its pronunciation.)

The second element of the compound brither-bairn is also Germanic in origin (< OE beran, ‘to bear’; beran, ‘child’, > ME bearnes, n. genitive ‘child’s’; barnes pl. ‘children’). Bairn has cognates in Old Frisian (bern), Old Saxon, Old High German, Middle High German, Gothic, Old Norse, Danish, Swedish (barn), and Middle Dutch (baren).[59]

Its earliest attestation appears in the Old English epic poem Beowulf, c. 1000:

‘Bēowulf maþelode, bearn Ecgþēowes’ [‘Ecgþeow spoke to his son Beowulf’][60]

And its first attestation in Middle Scots is recorded in Complaynt Scotland, c. 1550:

‘It is fors to me & vyf and bayrns to drynk vattir’[61]

N.B. The principle chronological periods in the history of Scots are commonly defined as shown below:[62]

-

Old English (Pre-Scots) – c.450 to c.1100

-

Older Scots – c.1100 to c.1700

Pre-Literary Scots – c.1100 to c.1350

Early Scots – c.1350 to c.1450

Early Middle Scots – c.1450 to c.1550

Late Middle Scots – c.1550 to c.1700

-

Modern Scots – c.1700 to present

Although the compound noun brither-bairn, in the sense of ‘cousin’, is found chiefly in Scots from the 1900s (compare with Old Frisian brōtherbern), it was first attested to mean ‘brother’s son’ or ‘nephew’ in Old English c. 1000. As the line below from Beowulf indicates, broðor bearn was used in the form of a compound with simple unmarked genitive (the genitive case is predominantly used for showing possession):

‘þeah ðe he his broðor bearn abredwade’ [‘although he had killed his brother’s son’][63]

By comparison with Modern English and Modern Scots, Old English and Older Scots were highly inflected languages (whereby the ending of some words change depending on their grammatical function in a sentence). For example, in Middle Scots bayrnis bed (‘bairn’s-bed’ or ‘womb’), the inflection <-is> is added to the root bayrin to indicate possession (i.e. the baby’s bed is the womb), while the <-s> suffix in singular vomans indicates that the womb itself belongs to a woman:

‘Ane vomans bayrnis bed’[64]

Although bairn has been retained in northern English as well as Scots, the compound brither-bairn is mainly attested in Scots, though its use is not restricted to Caithness.

Dander—n. A listless stroll. “I wis awa’ havin’ a dander.”

Another word of obscure origin, dander (also daunder, dauner, dawner, daander) was formed in English by conversion from a verb to a noun.[74][75] Commonly used in later Scottish and northern English dialects, its earliest attestation in Older Scots appears in the form of a verb, meaning ‘to stroll or saunter’, in John Burel’s 1590 Passage of the Pilgremer:

‘The he fox […] Quhiles wandring, quhiles dandring’[76]

Suggesting that dander is a frequentative variant of EMnE dandle and/or Old Scots †dandill, the SND cites numerous cases of the noun form, meaning ‘a stroll, a slow walk’.[77] Its earliest citation in this sense appears in John Galt’s 1821 novel Annals of the Parish and is linked to the Ayr variant dawner:

‘I was taking my twilight dawner aneath the hedge’[78]

Recorded as being in current use, the most recent documented citation specifically linked to Caithness is taken from the Caithness-born author James Miller’s novel A Fine White Stoor, published in 1992:

‘At last the cart was full, its tyres bulging and sinking a little in the heathery mattress, but before the homeward trip Dougie decided on a dander up the brae.’[79]

It has been suggested that the variant dandle may be cognate with German tändeln, meaning ‘to dawdle, toy, trifle, dally, play, dandle’.[80] However, given that dandle is not attested before the 16th century, either in Old or Middle English, it has also been proposed that this word may derive from Italian dandola, a variant of dondolare, ‘to swing, toss, shake to and fro; dally, loiter, idle’.[81]

This uncertainty not only resonates with the sort of obstacles faced by writers like Nicolson and Horne, but also highlights one of the many challenges facing 21st-century English and Scots etymology (the study of the origin and history of words).

Neever Day—n. New Year’s Day. The day before Neever Day is Neever even.

The compound ‘New Year’s Day’ is Germanic in origin and has cognates in Middle Dutch niejaersdach, nieujaersdach (Dutch nieuwjaarsdag), German Neujahrstag, Old Icelandic nýjársdagr, Old Swedish nyars dagher (Swedish nyårsdag), and Danish nytårsdag.[82] The earliest recorded use in Middle English appears in the Ormulum c. 1175:

‘Tatt daȝȝ iss newȝeress daȝȝ Mang enngle þeode nemmnedd’[83]

There are a number of reduced forms recorded in Scots (e.g., n’yer, new(e)r-, neuer, ne’(e)r-, ne’ar, nair-, nu(i)r-, noor(s), and Caithness nivər-).[84] The reduced form ‘New Year(s)’ also appears in Middle English. See, for example, John Gower’s Confessio Amantis composed in 1393:

‘The frosti colde Janever, Whan comen is the newe yeer’[85]

However, the variant Neever Day seems to have been restricted to Caithness and Orkney. Never Day (along with the tautological form Neever even) is recorded in Horne’s 1907 County of Caithness,[86] and the SND records an instance of Neever even in Orkney with a composition date of 1964.[87]

We know that the graphemes <w> and <v> (and <u>) were used interchangeably in Older Scots, but occasionally when the medial consonant <v> was substituted for <w> (and vice-versa), it reflected a contrast in pronunciation.[88] It is possible, therefore, that the Caithness form Neever is indicative of a [v] pronunciation at the time, rather than the [w] phoneme retained in Modern Scots and Modern English.

Shither—n. People, folk in general, natives of a particular district, kinsfolk

Although the meaning of shither was not disputed in the times of Nicolson and Horne, there was some disagreement in the local community about the alternative spelling chither.

Some correspondents, contends John Mowat in a newspaper clipping from the Caithness Dialect album, ‘have recently taken to writing the Caithness word “shither,” as “chither”’. Vexed by the <ch> development, Mowat writes:

‘I want to say emphatically that [the chither] spelling does not bear out the pronunciation of the word as I have heard it in Caithness, nor does it conform with the spelling set down by David Nicolson, John Horne and other standard writers.’

Mowat’s objection raises an important question about prescriptivism and usage. A prescriptive approach to language use expresses the attitude or belief that one variety of a language is superior to others and should be promoted as such. Mowat adopts this view with <chither>. He does not accept the variant <ch> because its spelling indicates the pronunciation [t͡ʃɪðər] (as in ‘chip’). His preferred form is <sh> because in his estimation it reflects the ‘correct’ Caithness pronunciation of [ʃɪðər] (as in ‘ship’).

However, modern linguistics adopts a descriptive rather than prescriptive approach. Its practitioners describe how language is used rather than prescribe how it should be used. As retrospective observers, one of the challenges we face is separating what designated authorities have accepted as the ‘correct’ form from other variants that may also have been in use.

Given that chither appeared in print as a variant of shither at the time (whether erroneously or otherwise), we need to be open to the possibility that it reflects actual usage, and on that basis accept it as a legitimate variant.

The form shither appears in David Houston’s Canisbay dialect poem ‘E Selkie Man’ in 1909:

‘E Strowma shither tried t’ get Kirsty owre wi’ ’em.’[89]

And in James Miller’s A Fine White Stoor in 1992:

‘Nobody but old shither for company.’[90]

However, chither is also attested as a Caithness form in 1932:

‘ ‘E Caithness chither in London’[91]

And a third variant schither appears in the Edinburgh John O’Groat Literary Society Journal in 1958:

‘If schither had got up and jived’[92]

It is also a point of interest that both shither and chither appear in the dialogue between Sandy and Tam in the John O’Groat Journal. Responding to Mr Lear’s comment on the ‘van of progress’ associated with ‘Caithness people’, Tam recalls ‘readin’ ‘boot ‘at Caithness chither’. And in another edition, Tam tells Sandy that the ‘Thirsa shither hed tae let their Provost speak first’. The speech of Sandy and Tam is intended to represent the Caithness dialect and was evidently written by someone who knew it intimately, which indicates that the writer was acquainted with the use of both forms.

Of uncertain origin, shither is a possible variant of the Orkney word cheelder, also Shetland cheelder, sheeldir, shielder, meaning ‘a child; a fellow’.[93] (The change from ‘sh’ to ‘ch’ is characteristic of Shetland.)[94] In any event, all the documented cases of shither (n.2) and its variants in the SND are linked to Caithness,[95] which suggests that shither in the sense of ‘people, folk, kinsfolk’ is indigenous to the county.

On a final shither note concerning Mowat’s objection to variant forms, which eloquently sums up his irritation and resistance to language change, he writes:

‘Of course the word means “people” or “folk,” and can never be used in the singular although I have heard “a Caithness shither,” which sounds stupid.’

Afterword

Notwithstanding recent advancements in sociolinguistics and the discipline’s impact on the way dialectologists study regional varieties, the Caithness Dialect album represents a rich slice of Caithness history and northern Scots dialectology at the fin de siècle and into the early 20th century.

Whether you’re interested in the Caithness dialect because it’s your own variety, or you are a dialectologist or historical linguist studying Scots varieties, it is well worth visiting the Caithness Archives to consult the album in person.

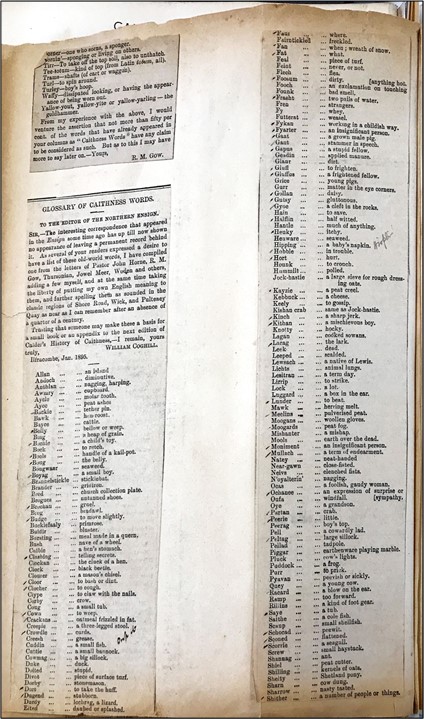

We hope to see you soon. Until then, please take a look at William Coghill’s ‘Glossary of Caithness Words’ from the Northern Ensign, which has been cut and pasted into the Caithness Dialect album.

How many words do you recognize? How many have fallen out of usage? And how many would you like to learn more about?

William Coghill’s ‘Glossary of Caithness Words’ printed in the Northern Ensign in 1895 — A Collection of Caithness Dialect 1933 (Ref. P130)

Read more Stories From The Archive

References

[1] Madison Marshall, ‘Influencing Future Thought: Julia Wedgwood’s Assembled Albums’, Reading Kinship: Intellectual Influence, Authorial Formation, and the Father-Daughter Relationship of Hensleigh and Julia ‘Snow’ Wedgwood, PhD thesis, The University of Leeds (White Rose eTheses Online, November 2022, embargoed to November 2024), Ch. 3.

[2] ‘In Memoriam: Pastor John Horne, Ayr. Caithness Author and Poet’, Obituary Notices and Tributes from the John O’Groat Journal (John O’Groat Journal Office, Wick, 1935) [ID: QZP40_CAITHNESS_PDF_001. Asset ID: 49482, © Am Baile], p. 16.

[3] North Coast Visitor Centre, Caithness Horizons Collection [ID: CAITHHORZ_THUFM_PH360. Asset ID: 4668, © Am Baile].

[4] Northern Ensign has been digitised and made available on the British Newspaper Archive (5 January 1854 – 6 October 1926). Available from: https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/titles/northern-ensign-and-weekly-gazette. [Accessed 18 November 2022].

[5] ‘In Memoriam: Pastor John Horne’, pp. 6–7.

[6] Gravestone Photographic Resource (GPR), GPR grave numbered 89829. Record number 196103 on the GPR database table. Available from: https://www.gravestonephotos.com/public/gravedetails.php?grave=89829. [Accessed 18 November 2022].

[7] ‘Public Appreciation of Pastor John Horne, Ayr. His Literary and Other Works for Caithness. Warm Tributes to His Achievements. Mr Horne’s Interesting Reply’. Reprinted from the John O’Groat Journal, 22 July 1932. [ID: QZP40_CAITHNESS_PDF_002. Asset ID: 49483, © Am Baile], p. 14.

[8] Ibid.

[9] ‘Public Appreciation of Pastor John Horne’, p. 12.

[10] John Horne, Kaitness Fowk: Dialect Stories and Poems (John Humphries, Caithness, 1929).

[11] John Horne, A Canny Countryside (Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier, Edinburgh and London, 1896).

[12] John Horne, ‘First Notices of the First Edition’, Wick: In & Around It (Wick, William Rae, 1893, Second edition, [First edition, 1892]), p. i

[13] Matthew J. Gordon, ‘Language Variation and Change in Rural Communities’, Annual Review of Linguistics, 5:1 (2019), p. 437.

[14] Joseph Wright, The English Dialect Dictionary, 6 vols (Oxford, Henry Frowde, 1898–1905).

[15] Manfred Markus, ‘Wright’s English Dialect Dictionary computerised: towards a new source of information’, Studies in Variation, Contacts and Change in English, vol. 2, (2007). Available from: https://varieng.helsinki.fi/series/volumes/02/markus/#wright_1898. [Accessed 2 December 2022].

[16] Ibid.

[17] Stuart Winter, ‘Batch, Bap or Bridie? Brits just can’t decide what to call the humble bread roll’ (Express, 27 September 2014). Available from: https://www.express.co.uk/life-style/food/516026/British-regional-names-for-rolls. [Accessed 1 December 2022]. Image © Craft Bakers’ Week.

[18] Urszula Clark, Studying language: English in action (Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), Ch. 1.

[19] John Jamieson, Supplement to the Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language (Edinburgh University Press, W. & C. Tait, 1825), p. 479.

[20] Walter Gregor, The Dialect of Banffshire: With a Glossary of Words Not in Jamieson’s Scottish Dictionary (Published for the Philological Society, London and Berlin, Asher & Co., 1866), p. 69.

[21] GAWPUS, GAUPUS, n. Also gap(p)us, -as, -is, gaapus, -as, -is, gapos; gaipas, Scottish National Dictionary, 1700–, Vol. IV (1956). Available from: https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/gawpus. [Accessed 2 December 2022].

[22] ‘Scots Orthography: Written Scots’. Available from: www.scots-online.org. [Accessed 1 January 2023].

[23] Andy Eagle, Written Scots in Scotland and Ulster: A review of traditional spelling practice and recent recommendations for a normative orthography (Dundee, Evertype Publishing, 2022), p. 29.

[24] James Y. Mather and Hans H. Speitel (eds), The Linguistic Atlas of Scotland, 3 vols (London: Croom Helm, 1975, 1977, 1986).

[25] David B. Nicolson, ‘Dialect’, The County of Caithness, edited by John Horne (Wick, William Rae, 1907).

[26] James Y. Mather, ‘The dialect of Caithness’, Scottish Literary Journal Supplement 6 (Aberdeen, Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 1978), pp. 3–4.

[27] Chamber Scots Dictionary, compiled by Alexander Warrack with an introduction and dialect map by William Grant (Cambridge, The University Press, 1911).

[28] Pierre Swiggers, ‘Linguistic historiography: object, methodology, modelization’, Todas as letras, 9:14, No. 1 (São Paulo, 2012), p. 42.

[29] John Mowat, The Place=Names of Canisbay, Caithness (Coventry, privately printed for the Viking Society for Northern Research by Curtis & Beamish, 1931), p. 2.

[30] Ibid, p. 1.

[31] Michael Barnes, ‘Jakob Jakobsen and the Norn Language of Shetland’ (1996). Available from: https://www.ssns.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/01_Barnes_ShetlandNL_1996_pp_1-15.pdf. [Accessed 15 December 2022], p. 3.

[32] Peter Trudgill, Investigations in Sociohistorical Linguistics: Stories of Colonisation and Contact (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[33] David Murison, The Guid Scots Tongue (The Mercat Press, Edinburgh, 1977); ‘Norse Influence on Scots’, Lallans, 13 (Edinburgh, 1979), p. 53.

[34] Michael Barnes, A New Introduction to Old Norse, Part I: Grammar (Third Edition, Viking Society for Northern Research, London, University College, 2008), p. 1.

[35] Marjorie Lorvik, ‘The distinctiveness of the Doric: home-grown or imported?’, Association for Scottish Literary Studies (14 December 2005).

[36] Inga Særheim, ‘Low German influence on the Scandinavian languages in late medieval times – some comments on loan words, word-forming, syntactic structures and names’, AmS-Skrifter, 27 (2019).

[37] Michael Barnes, ‘The Study of Norn’, Northern Lights, Northern Words, Selected Papers from the FRLSU Conference, Kirkwall 2009, edited by Robert McColl Millar (Aberdeen, Forum for Research on the Languages of Scotland and Ireland, 2010), p. 27.

[38] Per Thorsen, ‘The Third Norn Dialect – That of Caithness’ (The Viking Congress, Lerwick, 1950).

[39] ‘The Caithness Earldom Papers 1767-69’, John Mowat Collection, Caithness Archives (P/MOW/6/1).

[40] Per Thorsen, op. cit.

[41] Michael Barnes, ‘The Study of Norn’, op. cit., pp. 27–28.

[42] ‘Indo-European Languages’, World History Encyclopedia (2014). Available from: https://www.worldhistory.org/Indo-European_Languages/. [Accessed 20 December 2022].

[43] ‘What is Scots?’, Dictionaries of the Scots Language. Available from: https://dsl.ac.uk/about-scots/what-is-scots. [Accessed 20 December 2022].

[44] Kurt C. Duwe, ‘Cataibh an Ear & Gallaibh (East Sutherland & Caithness)’, Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies 1, Vol. 22 (Second Edition, 2012). Available from: http://linguae-celticae.de/dateien/Gaidhlig_Local_Studies_Vol_22_Cataibh_an_Ear_Ed_II.pdf. [Accessed 15 December 2022], p. 13.

[45] Ibid., p. 16.

[46] Ibid., p. 13.

[47] J. Patten MacDougall, Registrar General of the 1911 Census (Scotland, Census Office, 1912).

[48] Alexander Mearns, ‘Gaelic Words in Caithness English’, SocArXiv (4 October 2019), pp. 1–2.

[49] W. F. H. Nicolaisen, ‘Scandinavians and Celts in Caithness: The Place-Name Evidence’ (1982). Available from: https://www.ssns.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/05_Nicolaisen_Caithness_1982_pp_75-85.pdf. [Accessed 20 November 2022], p. 75.

[50] David Nicolson, ‘Dialect’, op. cit., p. 66.

[51] ‘brither-bairn, cousin’, Wright’s English Dialect Dictionary, op. cit.

[52] ‘BRITHER4, brither-bairn’, Scottish National Dictionary. Available from: https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/brither. [Accessed 11 December 2022].

[53] Iain Sutherland, The Caithness Dictionary (Wick, 1991), p. 14.

[54] ‘BRITHER4, brither-bairn’, op. cit.

[55] ‘brother’, n. and int.’, Oxford English Dictionary. Available from: https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/23798?redirectedFrom=brither#eid. [Accessed 4 January 2023].

[56] Ibid.

[57] ‘BRITHER4, brither-bairn’, op. cit.

[58] ‘brother’, n. and int.’, op. cit.

[59] ‘bairn, n.’, Oxford English Dictionary. Available from: https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/14726?redirectedFrom=bairn#eid. [Accessed 4 January 2023].

[60] Beowulf: A Student Edition, edited by George Jack (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1997), p. 60, line 529.

[61] Robert Wedderburn, The Complaynt of Scotland (Paris, c. 1550), Ch. XV.

[62] For information about the history of the Scots language, visit the Scots Language Centre online. Available from: https://media.scotslanguage.com/library/document/Scots%20Timeline%20Pre-1700.pdf. [Accessed 10 December 2022].

[63] Beowulf, p. 179, line 2619.

[64] Wedderburn, Comp. Scot., Ch. VI.

[65] Nicolson, ‘Dialect’, p. 66.

[66] ‘CURRIESHANG, CURRY-, CARRIE-‘, Scottish National Dictionary. Available from: https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/currieshang. [Accessed 10 December 2022].

[67] ‘CUR-, Currie-’, Scottish National Dictionary. Available from: https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/cur. [Accessed 10 December 2022].

[68] Ibid.

[69] ‘Shangie’, Jamieson, Supp. Etymol. Dict. Sc. Lang, op. cit., p. 377.

[70] ‘COLLIESHANGIE’, Scottish National Dictionary. Available from: https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/collieshangie. [Accessed 3 January 2023].

[71] Ibid.

[72] Weekly Magazine Or Edinburgh Amusement (25 January 1776), p. 146.

[73] Nicolson, ‘Dialect’, p. 66.

[74] ‘dander, v.1’. Oxford English Dictionary. Available from: https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/47140#eid7427797. [Accessed 5 January 2023].

[75] ‘dander, n.5’, Oxford English Dictionary. Available from: https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/47139?rskey=mMWxIM&result=5&isAdvanced=false#eid. [Accessed 5 January 2023].

[76] John Burel, ‘The Passage of the Pilgremer’ (1590), James Watson’s Choice Collection of Comic and Serious Scots Poems, Vol. I, edited by Harriet Harvey Wood (Edinburgh and Aberdeen, Scottish Text Society, 1977), part iv, line 10.

[77] ‘DANDER, DANNER, Daunder, Dauner, Dander’ [see n.2], Scottish National Dictionary. Available from: https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/dander_v1_n1. [Accessed 5 January 2023].

[78] John Galt, Annals of the Parish; or the Chronicle of Dalmailing; During the Ministry of the Rev. Micah Balwhidder. Written by Himself (T. Cadell, London, 1821), p. ii.

[79] Miller, A Fine White Stoor, op. cit., p. 150.

[80] ‘dandle, v.,’ Oxford English Dictionary. Available from: https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/47149#eid7428629. [Accessed 3 January 2023].

[81] Ibid.

[82] ‘New Year, n.’, Oxford English Dictionary. Available from: https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/126656?redirectedFrom=new+year%27s+day#eid33474995. [Accessed 3 January 2023].

[83] The Ormulum (Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, MS. Junius 1, 1170–1185), line 4230.

[84] ‘NEW-YEAR, n.comb.’, Scottish National Dictionary. Available from: https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/newyear. [Accessed 3 January 2023].

[85] John Gower, Confessio Amantis (Fairf.) [vii, 1206], The English works, edited by George Campbell Macaulay (Early English Text Society edition, 1900–1901), EETS 81, 82.

[86] Nicolson, ‘Dialect’, p. 80.

[87] ‘NEW-YEAR, n.comb.’, op. cit.

[88] Ivan Herbison, Philip Robinson and Anne Smyth (eds), ‘Older Scots spelling and its legacy in modern Ulster-Scots’, Ulster-Scots Language Guides: Spelling and Pronunciation Guide (First Edition, Belfast, Ullans Press, 2013).

[89] David Houston, ‘E Selkie Man’, (1909), 5.

[90] Miller, op. cit., p. 117.

[91] John O’Groat Journal (4 November 1932).

[92] Cited under ‘SHITHER, n.2’, Scottish National Dictionary. Available from: https://www.dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/shither_n2. [Accessed 5 January 2023]. N.B. Caithness Archives holds some records for the Edinburgh John O’Groat Literary Society (est. 1922) dating from 1892 to 1973 (Ref. GB1741/ P751).

[93] ‘CHEELDER, Sheeldir, Shielder, n.’, Scottish National Dictionary. Available from: https://www.dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/cheelder. [Accessed 5 January 2023].

[94] Derrick McClure, ‘Distinctive semantic fields in the Orkney and Shetland dialects, and their use in the local literature’, Northern Lights, Northern Words, edited by Robert McColl Millar (Aberdeen, Forum for Research on the Languages of Scotland and Ireland, 2010).

[95] ‘SHITHER, n.2’, op. cit.

![Pastor John Horne and his wife Margaret Horne (née Morrison) [3]](https://www.highlifehighland.com/nucleus-nuclear-caithness-archives/wp-content/uploads/sites/121/2023/01/Pastor-John-Horne-and-his-wife-Margaret-Horne-750x1024.jpg)

![Historical counties and dialect regions of England, Scotland and Wales[16]](https://www.highlifehighland.com/nucleus-nuclear-caithness-archives/wp-content/uploads/sites/121/2023/01/Historical-counties-and-dialect-regions-of-England-Scotland-and-Wales16.png)

![Dialect map of UK showing the anecdotal distribution of regional names used for bread[17]](https://www.highlifehighland.com/nucleus-nuclear-caithness-archives/wp-content/uploads/sites/121/2023/01/Dialect-map-of-UK-showing-the-anecdotal-distribution-of-regional-names-used-for-bread17-691x1024.jpg)

![The Germanic branches of the Indo-European language family tree [42]](https://www.highlifehighland.com/nucleus-nuclear-caithness-archives/wp-content/uploads/sites/121/2023/01/Picture15.png)

![Indo-European language family tree illustrating the Germanic, Celtic and Italic branches [43]](https://www.highlifehighland.com/nucleus-nuclear-caithness-archives/wp-content/uploads/sites/121/2023/01/Picture16.png)