‘Government will yield nothing to justice, but a great deal to fear’

– Hugh Miller, 1846 [1]

A Brief Introduction

The above quote is from a private letter of Hugh Miller who worked for the pro-Free-Church newspaper Witness. Miller is lamenting the ‘quiescence’ that Highlanders and Islanders in Scotland were showing in response to the rapidly intensifying famine caused by potato blight.

He refers to the Irish rebellions that were demanding the government and landowners come to the aid of the population:

‘they are buying guns, and will be by-and-by shooting magistrates… by the score, and parliament will in consequence do a great deal for them’ [2]

Very soon, however, there were riots and rebellion across the Highlands and Islands. In this edition of Stories From The Archive we’d like to focus on the grain riots that broke out across Caithness in 1847.

We’ll do this by exploring our local authority records. The Caithness Archive is charged with preserving historic local authority records for posterity. This sits alongside our role of collecting more widely from individuals, organisations and businesses across the county.

We’ll investigate how the records of the Commissioners of Supply can shed light on the grain riots. This will allow the stories and circumstances that led up to these events to be revealed.

Author: Commissioners of Supply

The Commissioners of Supply were first established in 1667 for the sole purpose of collecting the cess, or national land tax. However, after 1800, and until the establishment of the county councils in 1889, which ‘destroyed the commissions in all but name’, the duties of the commissioners were based on the collection and supervision of local taxes.

They were an institution which represented only the landed classes. Indeed, they were the chief organ of the politicised Scottish landowners. As such, the inherent bias of the records, and the narratives they expose, must be considered carefully. We will also explore other sources of information to balance this bias. This will allow for a more encompassing representation of the events of 1847.

The Commissioners of Supply continued to exist as an institution until 1930, mainly because membership qualified men for certain local and national offices. However their influence and power practically vanished after the passing of the The Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889. This important legislation paved the way towards a more democratic local government system.[3]

Provenance: Local Authority records

As a local authority archive, the Caithness Archive is responsible for preserving and making accessible the historic records of the County of Caithness. As local government records age and their day-to-day use is no longer needed, a decision has to be made as to their long-term importance.

Our team of archivists are responsible for identifying records that have heritage and cultural value. Those which are identified are then accessioned into the archive collections and made accessible to the public.

Format: Minute book

The term ‘minute book’ is a name given to two distinct types of historical record in Scotland. The first is a record of a meeting of a corporate body (such as a local authority committee or private company). The second type of minute book is a digest of a legal register or court record.

The origins of both lie in the medieval Latin term ‘minuta scriptura’, meaning ‘small writing’. By the 17th century the term ‘minute books’ was used in relation to the official record of the meetings of corporate bodies, such as commissioners of supply and kirk sessions, but separate minute books for legal registers and court records continued to be made by court officials.[4]

Potato Blight and Famine in Ireland and the Highlands and Islands of Scotland 1846

The Irish Famine was an awful and global event. More than a million emigrants left the shores of Ireland to settle in far-off lands.

In the mid-1840s, Scotland had to deal with the consequences of its own potato famine. By December 1846, William Fraser-Tytler, Sheriff of Inverness, was warning that some parts of his Highlands and Islands sheriffdom were suffering as badly as those in Ireland. Crops were devastated and communities were left without any source of staple food.

James Hunter explains that:

‘In both Scotland and Ireland, Whig ministers believed, rural populations at risk of starvation needed to look for assistance, in the first instance, to landlords who, given their insistence that governments should have nothing to do with how they managed their estates, could hardly object (in public at least) to being handed this responsibility. But what if no such assistance was forthcoming?’ [5]

The Caithness Situation and the Corn Laws

Photo by Brick to the Past available <http://www.bricktothepast.com/blog-to-the-past/category/protest>

The effect of potato blight was felt within the county of Caithness. People turned to oatmeal to replace the potato staple that was no longer available. Destitution rapidly became of growing concern due to the rising cost of oatmeal. This rise in price was caused by landlords, farmers and dealers who continued to export grain from Caithness. This was done to take advantage of higher prices in the south.

The Corn Laws of the time were designed to keep corn (all cereals) prices high to favour domestic producers, and represented British mercantilism. The Corn Laws blocked the import of cheap corn, initially by simply forbidding importation below a set price, and later by imposing steep import duties, making it too expensive to import it from abroad, even when food supplies were short, or withheld.

This concoction of law and greed meant that the communities of Caithness, already suffering from a downturn in fishing incomes, were driven further into situations of poverty.

A John O’Groat Journal article from the 12th of February 1847 describes the grain situation very well:

‘While they are starving, the granary lofts in the neighbourhood are groaning under the weight of thousands of quarters of oats and bear, raised to a famine price, by undue competition, and placed far beyond the capabilities of even the employed labouring classes.’ [6]

Unrest Across the County

Driven by hunger, and beset by the insensitivity of the governing authorities, huge crowds gathered in Thurso, Castlehill and Wick in January and February of 1847 to prevent the export of grain from a starving county. The John O’Groat Journal explains how:

‘cargo vessels were boarded and their crews threatened. The Riot Act – entitling the authorities to take drastic measures against protesters – was read, with no effect’[7]

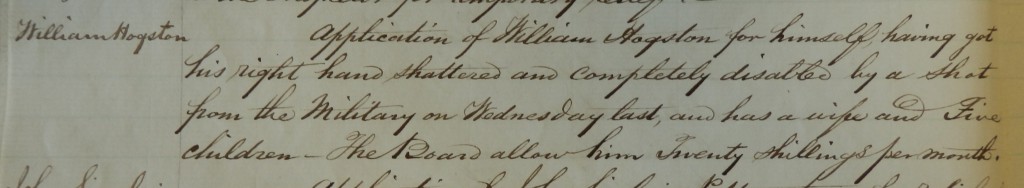

The Wick Parochial Board minutes of 2nd March 1847 give insight into the events that unfolded in Wick and Pulteneytown.

The minutes read:

‘Application for William Hogston for himself having got his right hand shattered and completely disabled by a shot from the Military on Wednesday last, and has a wife and five children. The Board allow him Twenty Shillings per month’

The story of how William Hogston came to be shot on that cold February night is a dramatic one. On the night of Friday 19th February 1847 word spread that another shipment of grain was to leave the harbour.

A crowd blockaded the harbour entrance and filled the boat that was to take the grain with stones. The Riot Act was read, but the crowd refused to disperse. There was a standoff over the weekend, and then on the following Monday a company of over 100 soldiers arrived by steamer from Aberdeen.

Under the protection of their rifles the boat was loaded with grain late on the afternoon of Wednesday 24th, and a squad of soldiers was stationed to guard the quay overnight.

A crowd gathered and began to taunt the soldiers, some throwing stones. James Hunter vividly describes the scene:

‘So heavy were some of those stones that one of them shattered the wooden stock of a soldier’s musket; others, “thrown with great violence” and curving down from high above, inflicted injury after injury on men whose progress was thus brought to a halt. “I was struck with stones several times,” said Corporal Cormick Dowd who “had his head cut through his cap.” “My arm was black [from a] severe blow,” said Private John Carr. A stone “knocked the firelock” from his grasp, said Private Richard Broome. “The stones were rattling on our bayonets,” said Private Daniel Connery. I was hit between the shoulders with a large stone which knocked me flat to the ground.… When I got the blow I said I would stand this no longer, and it was as good to kill another as for oneself to be killed. With the situation escalating the guard called for reinforcements and the streets were cleared in a bayonet charge. Three people were arrested, and the soldiers marched them off to gaol’[8]

Their route took them along Union Street (pictured above), at the foot of the brae that runs along Sinclair Terrace where the Library stands today; another jeering crowd collected along the top of the brae and soon started throwing stones down onto the soldiers as they passed below.

The Sheriff ordered the soldiers to open fire up the brae and into the crowd. A young woman whose name was Macgregor was hit on the arm, but not seriously, while William Hogston had his hand shattered by a musket ball.

The John O’Groat Journal reported that William, a cooper by trade, had been making his way quietly home when he was caught in the firing; his hand was so mutilated that the fingers had to be amputated. With his means of earning a living gone, he had no alternative other than to approach the parish and ask for poor relief, which as the minutes tell us, was granted at a rate of five shillings a week.

Response of the Commissioners of Supply

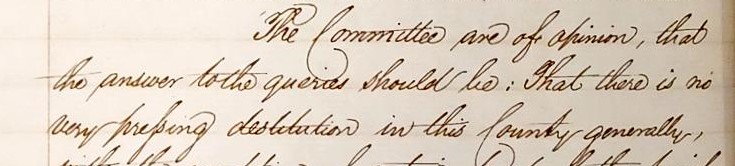

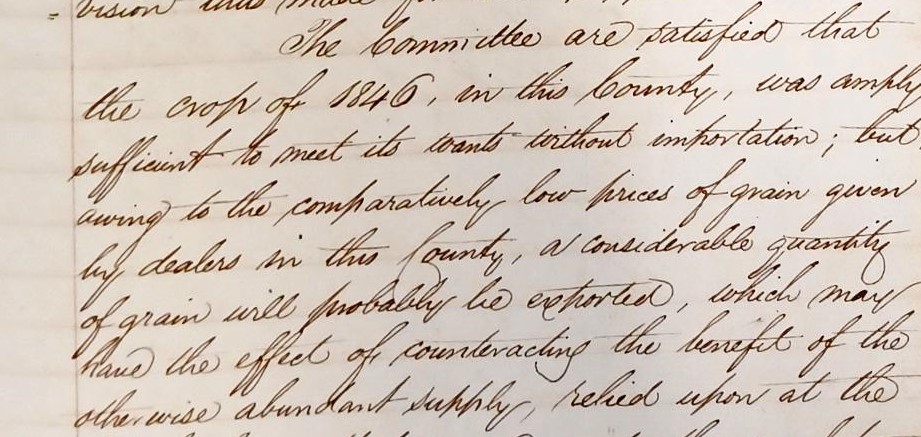

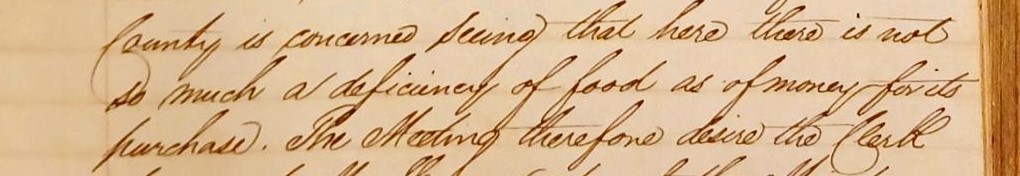

The Commissioners of Supply were an institution which represented only the landed classes. Their response to the unfolding situation in Caithness is a reflection of this. Below are some extracts from the Commissioners of Supply minute book. They describe discussions and decisions made at meetings in January, February and March of 1847:

‘The Committee are of opinion, that the answer to the queries [of the Highland Destitution Committee] should be: that there is no very pressing destitution in this County’

‘The committee are satisfied that the crop, of 1846, in this County, was amply sufficient to meet its wants without importation; but, owing to the comparatively low prices of grain given by dealers in this County, a considerable quantity of grain will probably be exported, which may have the effect of counteracting the benefit of the otherwise abundant supply’

‘here there is not so much a deficiency of food as of money for its purchase’

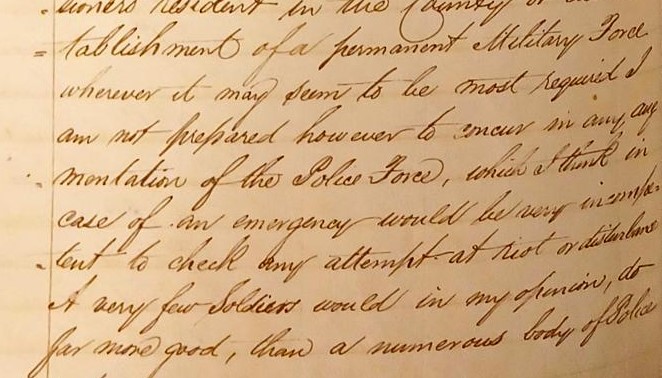

‘establishment of a permanent Military Force… to check any attempt at riot or disturbance’

The entries speak for themselves and give an insight into the governing structure that led many across the county to believe they had no other choice but to take the law into their own hands. We began this edition with a quote which seems to ring very true in light of the above:

‘Government will yield nothing to justice, but a great deal to fear’ – Hugh Miller, 1846

Concessions and Consequences

The unrest led to cheaper food in the coming months and a firmer commitment from the powers that be to feed the population.

There was, however, many consequences to the upheaval, not least the story of Pulteneytown shoemaker James Shearer, who was condemned to transportation to a penal colony in Australia.

Wider Unrest across Highland and Further Reading

The unrest described above was in no way contained to Caithness. Across the Highlands and Islands communities rose up against the neglect shown by the ruling classes and the inadequacy of the systems of governance.

The rebellions and riots of 1847, by and large, had no wider political agenda and sought only to counteract the pressing risk of famine. It was not until some 35 years later that widespread unrest would break out again in the North of Scotland, this time with a stronger political goal – achieving, in part, a great advance in rights for the communities that first rose up in 1847.[9]

If you would like to learn more about these fascinating events we would recommend James Hunters book Insurrection: Scotland’s Famine Winter, which is a fascinating read. The story he tells is, by turns, moving, anger-making and inspiring. In an era of food banks and growing poverty, it is also very timely.

Read more Stories From The Archive

References

[1] James Hunter, Insurrection: Scotland’s Famine Winter (Birlinn Limited, 2019), p. 31.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ann E. Whetstone, Scottish County Government in the 18th and 19th Centuries (John Donald Publishers, Edinburgh, 1981), p. 61.

[4]Scottish Archives Network, ‘Knowledge Base – Minute Books’, SCAN (2000) <https://www.scan.org.uk/knowledgebase/topics/minutebooks_topic.htm>[Accessed 15 June 2022]

[5] James Hunter, Insurrection, p. 16.

[6] John O’Groat Journal, 12 Feb 1847

[7] John O’Groat Journal, 30 Sep 2019

<https://www.johnogroat-journal.co.uk/news/historians-new-book-reveals-story-of-violent-protests-in-wick-and-thurso-183698/>[Accessed 15 June 2022]

[8] James, Hunter, ‘’You must fire on them’: Protest and repression in Pulteneytown, Caithness, in 1847’, Studies in Scottish Literature, 46:1, (2020), p.41.

[9] James Hunter, Insurrection, p. 218.