A Brief Introduction to the Series

We all tell stories and revel in those of others. Our minds seem in many ways compelled to attain the heights of the fictitious and nothing, I would argue, can inspire or engage us more than a real-life account of something extraordinary. The past, in many ways, feeds this desire simply by being different, by intriguing us through its very otherness. Often do we find ourselves living vicariously through others, whether it be in fiction or not. These articles wish to engage you through the excitement of their content but also to ground their importance within the historical record; to show how thoroughly archival documents may illuminate and educate in equal measure. Moreover, when opportunity allows, we will strive to give further insight into the important role played by the archive staff in preserving, cataloguing & exhibiting these records.

When we think about archives we often think about old documents and books, perhaps there is a tendency to imagine boring bureaucratic reportage gathering dust, holding little contemporary worth. This could not be further from the truth. Everything held within an archive merits its place and offers a lens with which to more accurately delve into the past, to understand what came before and how it in turn is intrinsic to our lives now.

This shall be the first of a series of articles, available through our website, documenting the myriad stories held within the Caithness Archives. Perhaps the most exciting part of working within an archive is being surrounded constantly by stories from the past, lives lived, and lessons heeded or often not. Very often these stories are so compelling it is hard not to want to let everyone know about them. This series of articles wishes to quench this urge and share some of these fascinating stories and the documents which hold them. We shall begin by exploring the diary of James Robertson Youngson which documents part of his voyage to Melbourne from November 1884 until January 1885.

Author: James Robertson Youngson

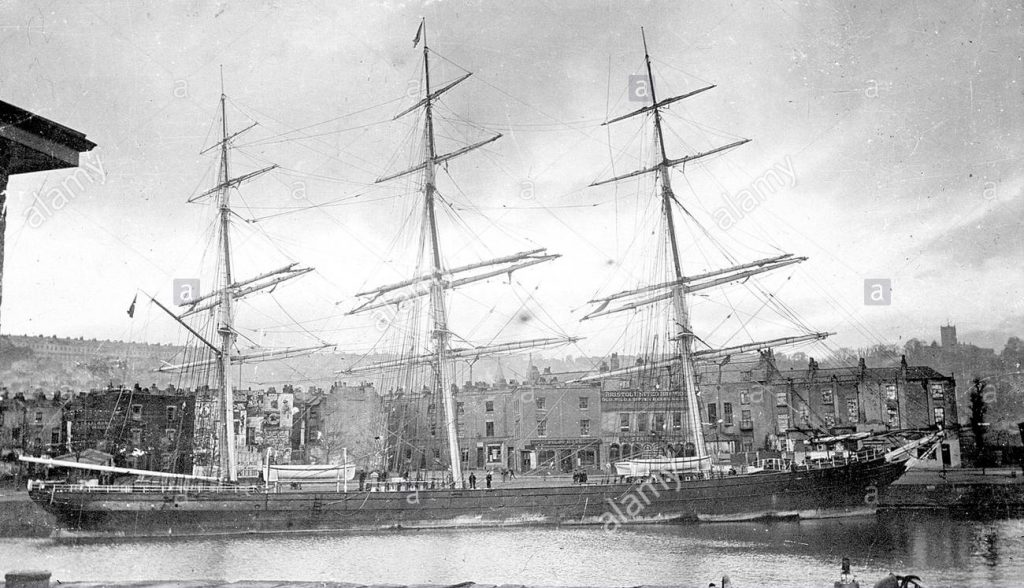

James Robertson Youngson was a passenger on a sailing vessel (we believe to have been the Arthurstone) bound for Melbourne from England, starting in 1884. James was the younger brother (by twelve years) of Reverend Alexander Youngson who was a minister at Strathy, located twenty miles west of Thurso. Alexander was born in Rosehearty, Pitsligo, Aberdeenshire in 1842 to Alexander Youngson (a baker) and Helen Chapman. James was born to the same parents on January 18th 1854, in Pitsligo, making him thirty years old when he started his journey and thirty-one by the end of it. Alexander was minister in Keith, Banffshire, married with five children aged nine and under in the 1881 census. James R. Youngson was an unmarried civil engineer, lodging with a Mrs Leas and her daughter in Kilmore and Kilbride, Argyllshire in the 1881 census.

Provenance: Private Deposit

Provenance is a fundamental principle of archives and details the individual, family or organisation that created or received the items in a collection. This diary was found in the West Manse, Strathy, in 1962 after the house had been sold following the death of Miss Alice Youngson. She was the daughter of Reverend Alexander Youngson who lived in the West Manse from 1909 until his death in 1933 (Caithness Archive also holds the pocket diaries of Reverend Youngson for the years 1911-1919). It was given to the archive as a gift.

Format: Diary

Diaries are biased, personal accounts of a person’s life. We must always be wary in attaching truth to personal accounts however, this could arguably be said of all records to some extent. All records in their way originate from a human source, diaries present us with a record that is extremely free to articulate and that feels the constraints of bureaucracy or business far less. Indeed, they may offer details lost to the official accounts due to this. In many ways they can complement and bolster other sources and perceived facts. They remain however, personal. They reveal one perspective, from one idiosyncratic experience, from a specific time and place. Their importance is not in the assistance they lend to objective truth but in the permission they give us to explore socio-cultural history through a common voice from the past. Diaries add colour and personality to official records. We know that a ship sailed from Britain to Australia in 1884-1885, we know which passengers were aboard, who the captain was and what the ship was carrying as cargo. Yet, without James’ diary this ship would have remained an empty vessel. Let’s explore the diary and hear, in James’ words, of the adventure he embarked upon.

The Diary

In order to give a comprehensive overview of the diary what follows shall be a narrative description with photographs of the diary pages which will enlarge when selected. This seems the best way to allow you to browse the diary freely whilst gaining further information about James’ journey.

Firstly, let’s set the scene as best we can. James does not mention the name of the ship he is sailing on however, after checking the unassisted passenger lists of arrival in Victoria, Australia we find that he arrived in February 1885 aboard the Arthurstone[1]. This is great to learn as the diary ends on the 29th of January whilst the ship is in the Southern Ocean. The diary may have continued as this was only the end of the notebook James was writing in. Unfortunately, this is the only one we have. On arrival, he was registered as J R Youngson, aged thirty-one. The Arthurstone was an iron barque (a sailing ship typically with three masts), weighing 1228 tons, built in 1876 by Gourlay Bros. Dundee and owned by Dundee Clipper Lines Ltd. It was later sold to Italy and renamed ‘Speme’ or Hope. Making the decision to take a ship to Australia may be quite unimaginable to most of us, especially a sailing vessel in 1884. We are never given a clear indication of James’ stimuli for going however, we may value his sense of adventure or impetus to leave as being quite stout in taking on such a daunting venture. A photograph of the Arthurstone is shown below.

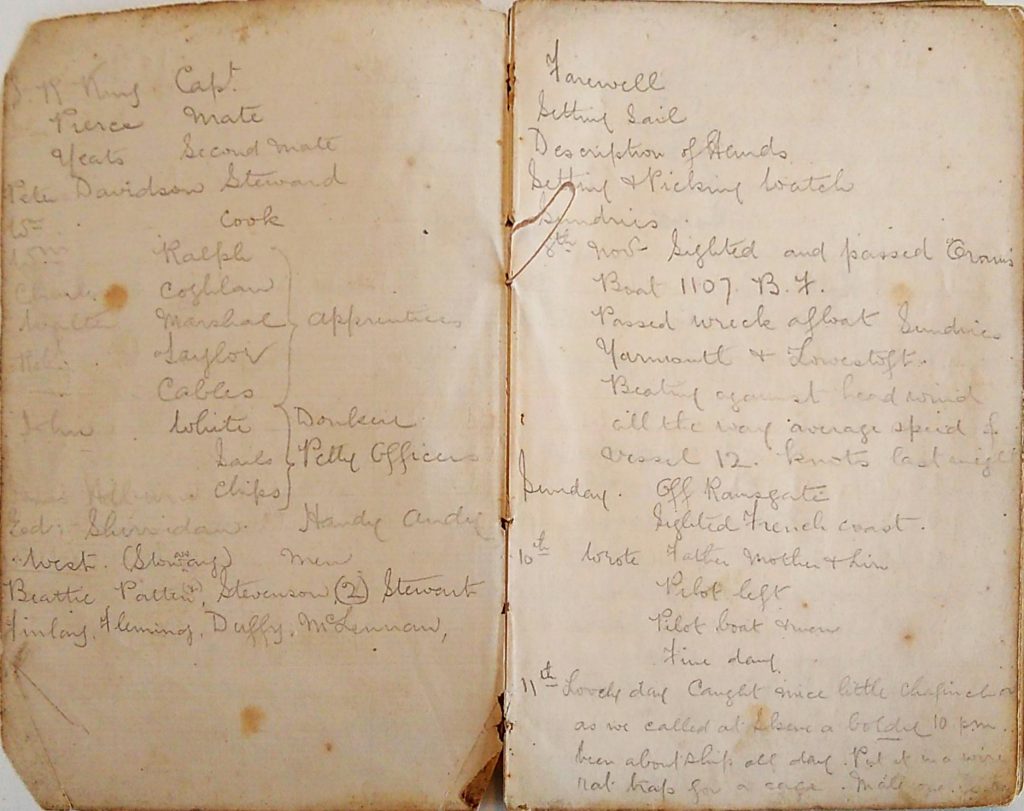

The diary itself begins with a list of the crew and men including the captain and first mate down to the cook and petty officers. These details are invaluable when names begin to be used throughout the diary; different roles aboard the ship are invested with detail and the experience of crew members are brought further to life. In the second of these two pages James announces ‘Farewell, Setting Sail’ and his dated entries begin, at first in short bursts, detailing their passing of a wreck, his writing to his father, mother and Liz and his capture of a chaffinch that has been onboard with them. As the diary progresses the entries become far longer. Click the diary pages below to enlarge.

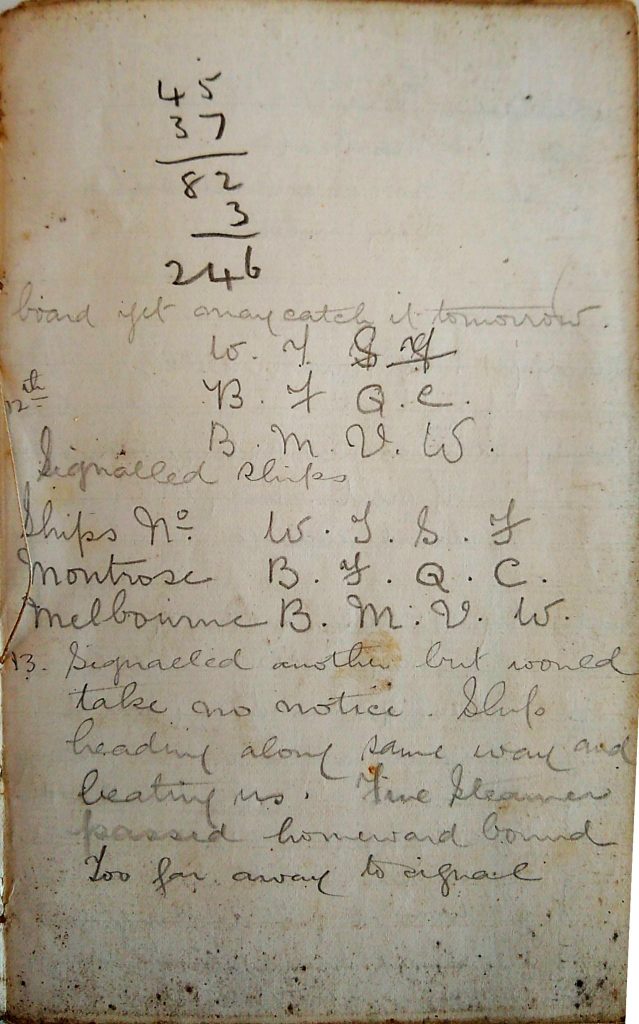

12th & 13th November 1884

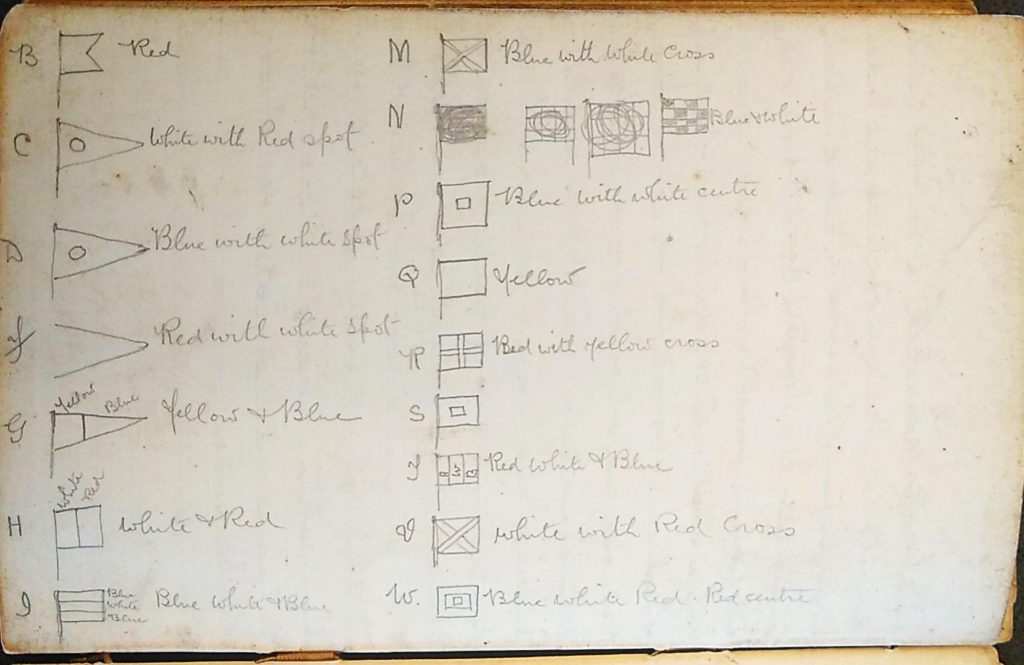

Here are the first of many references to the signalling of other ships using flags. Maritime signal flags have a long history and are still in use today. A series of flags can spell out a message, each flag representing a letter. Below are photographs of the 12th & 13th of November and to one of the back pages of the diary in which James has drawn some of the flags used.

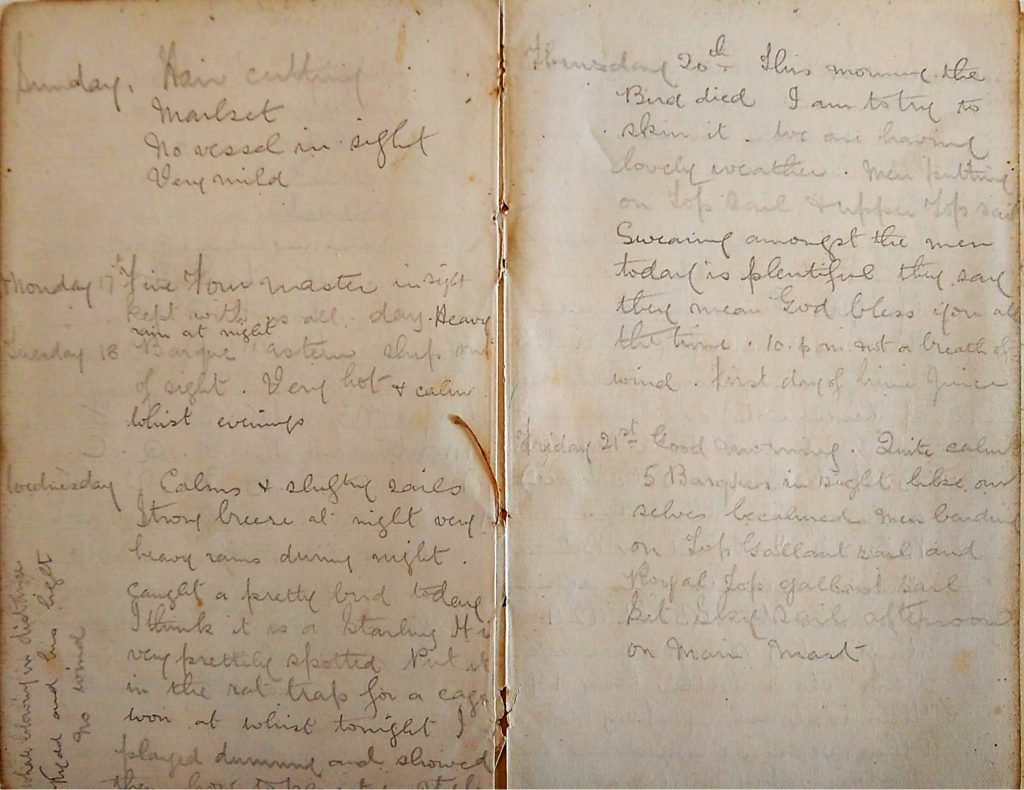

16th-21st November 1884

There are haircuts onboard, bouts of heavy rain, whales blowing in the distance and the capture of another bird. James also mentions a ‘Whist evening’. Whist is a card game that was widely played in the 18th and 19th century. James brags how he ‘played dummy and showed them how to play in style’. Snippets like these start to give us a better idea of James’ personality, they remind us of the human being writing the diary, that this is not an adventure novel, and a connection is born and with it an investment in his story.

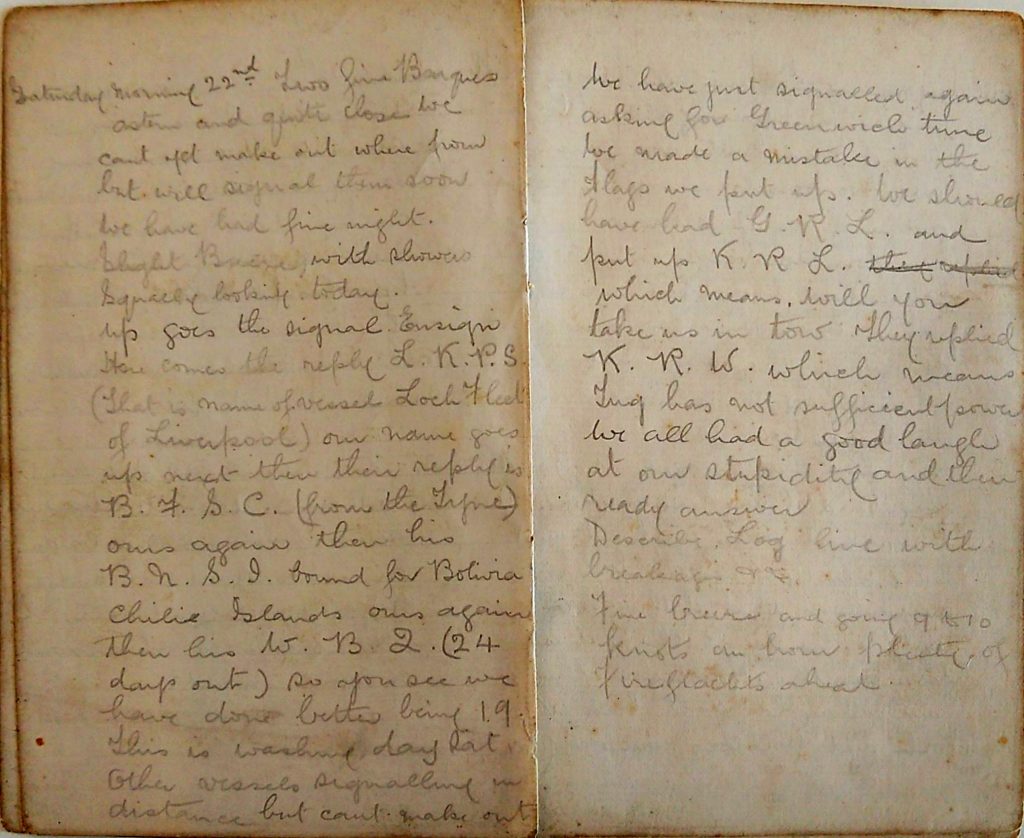

22nd November

The first of the longer entries, stretching over two pages. James sights more barques. More signalling to other vessels, exchanging destinations and the Greenwich time, with a mistaken message causing hilarity on board between the men.

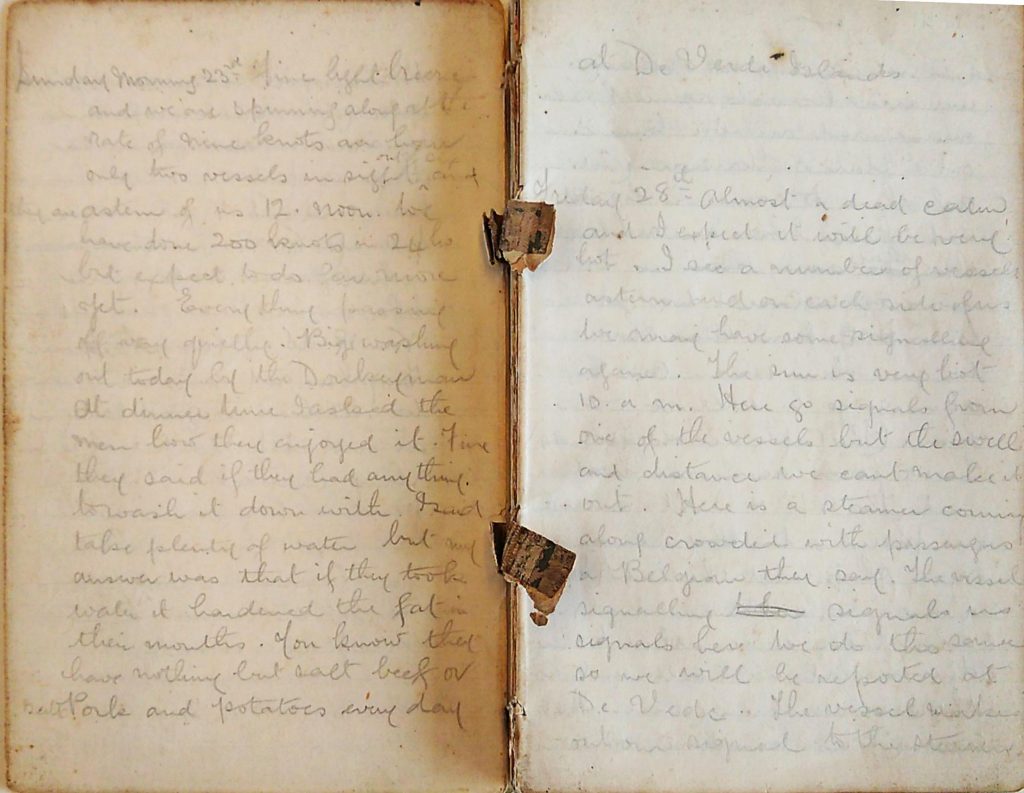

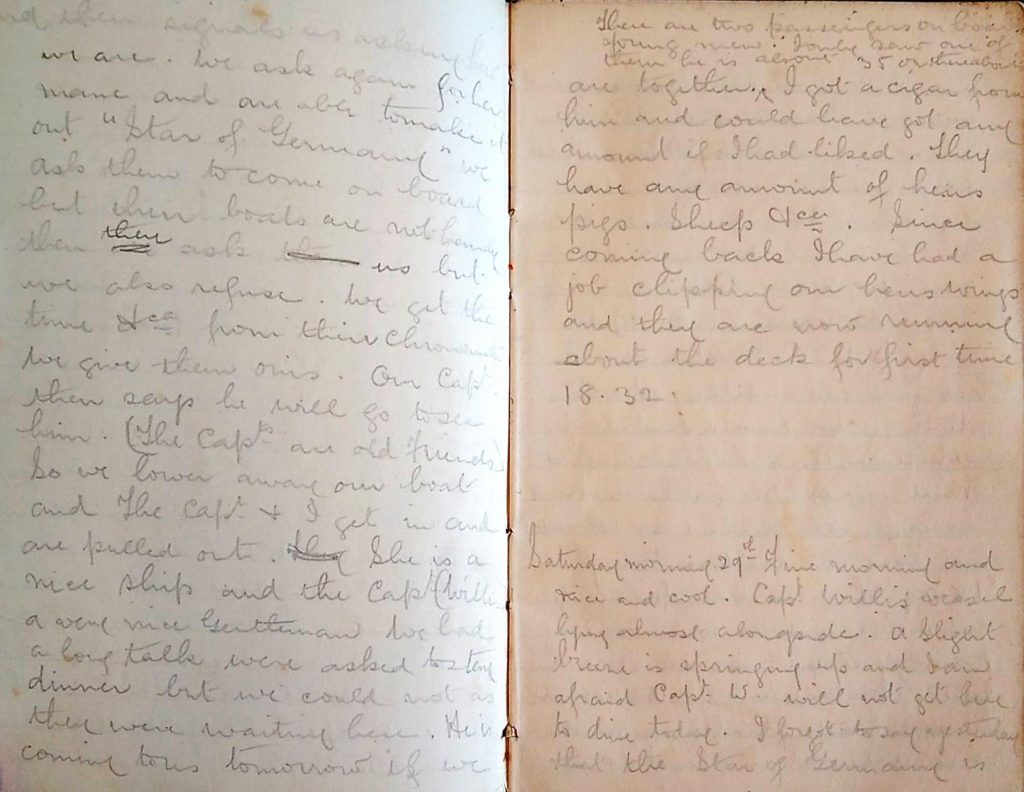

23rd-28th November 1884

A big washing gets hung out by the Donkeyman (the individual responsible for the Donkey engine, a steam powered winch engine, used to (un)load cargo, raise larger sails or power pumps, invented in 1881). We get our first insight into the diets onboard. James says of the men, ‘you know they have nothing but salt beef or salt pork and potatoes every day’. We also get our first mention of fellow vessel the Star of Germany. The captains we are told are old friends. James accompanies the captain on a small boat to visit the Star of Germany suggesting he is a passenger of some importance. Below is an additional picture of the Star of Germany.

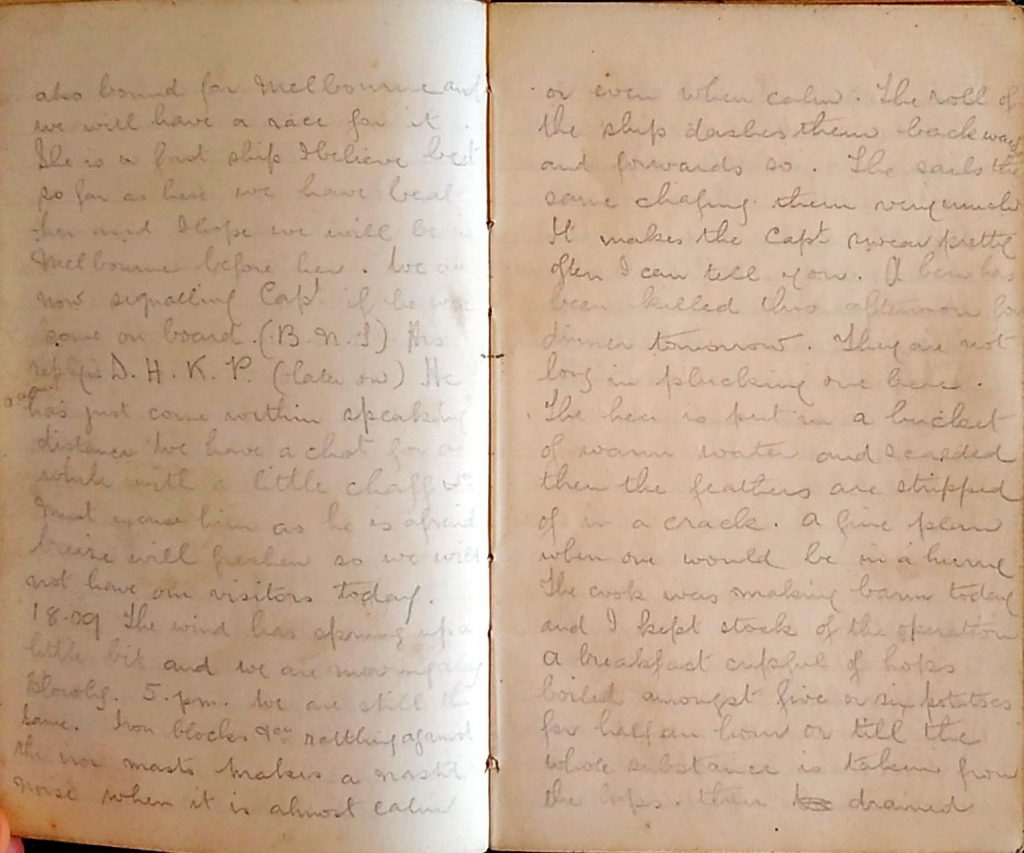

29th November 1884

Another lengthy entry spanning four pages. Further mention of Captain Willis of the Star of Germany, which is also headed for Melbourne. ‘We will have a race for it’, James says. He also remarks that ‘barm’ is being made by the cook. Barm was a soft bread roll named after the foam on top of beer which was used to help the bread rise. James says the bread is ‘splendid…better I think than on shore’. Mention also that a hen is killed and plucked for dinner.

30th November

‘The last day of November’, James affirms. Good weather persists and the Star is off ahead. ‘We have at last sighted land’, he tells us, ‘the island of St Antonio is on our lee side and I should say about thirty miles off’. This may well be the island of Santo Antão of the Cape Verde islands off the coast of Mauritania. This would set the Arthurstone on the usual clipper route (graphic below) to Australia which normally ran south through the western South Atlantic. Mention of the Van Demen another ship bound for Iquique in Chile makes this even more likely. The Van Demen signals asking if they have a surgeon on board to help an injured man.

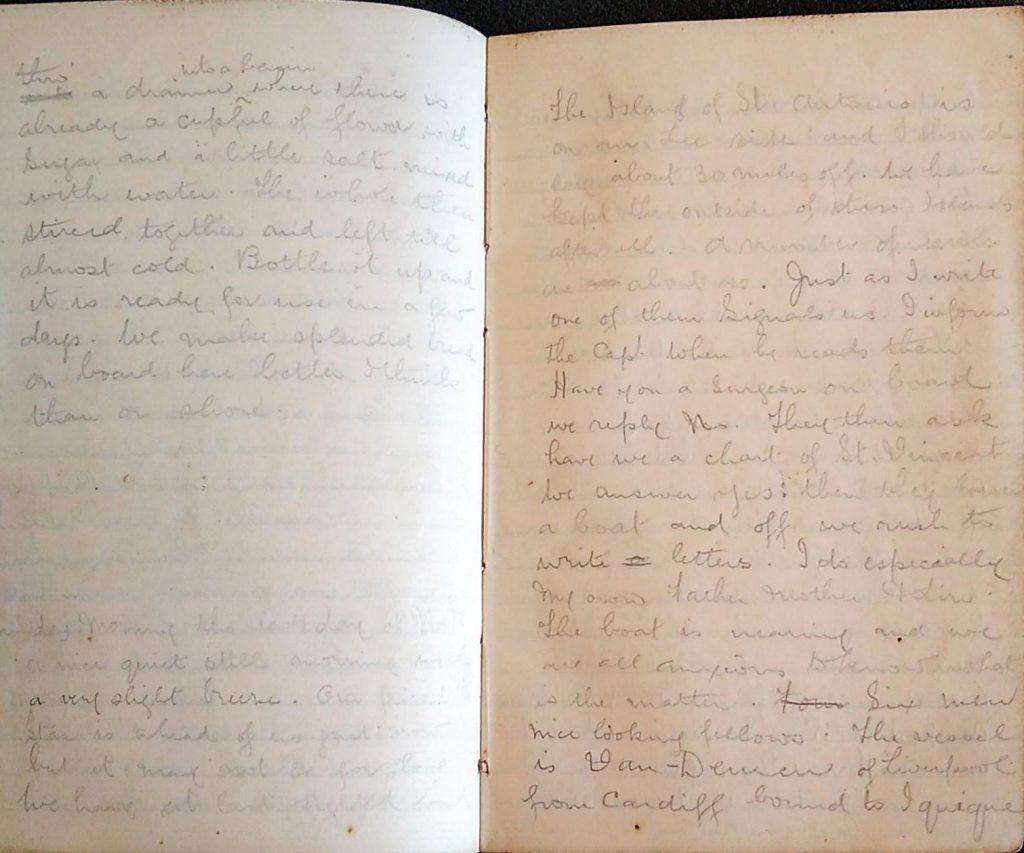

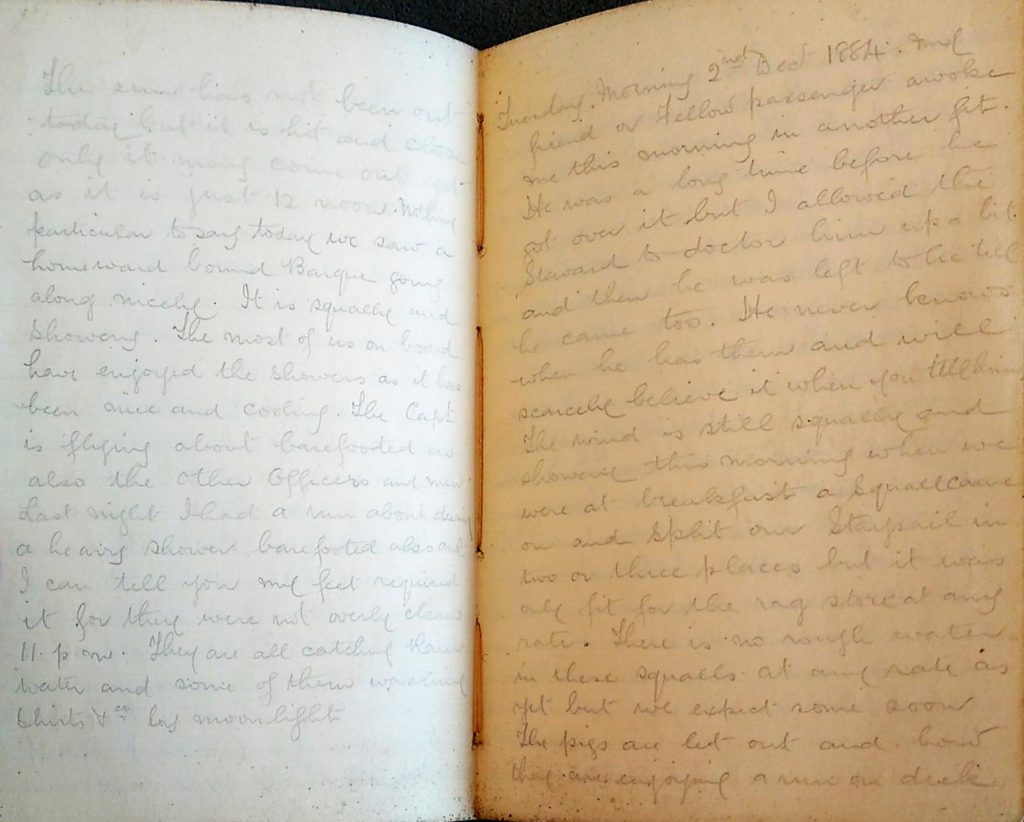

1st-3rd December 1884

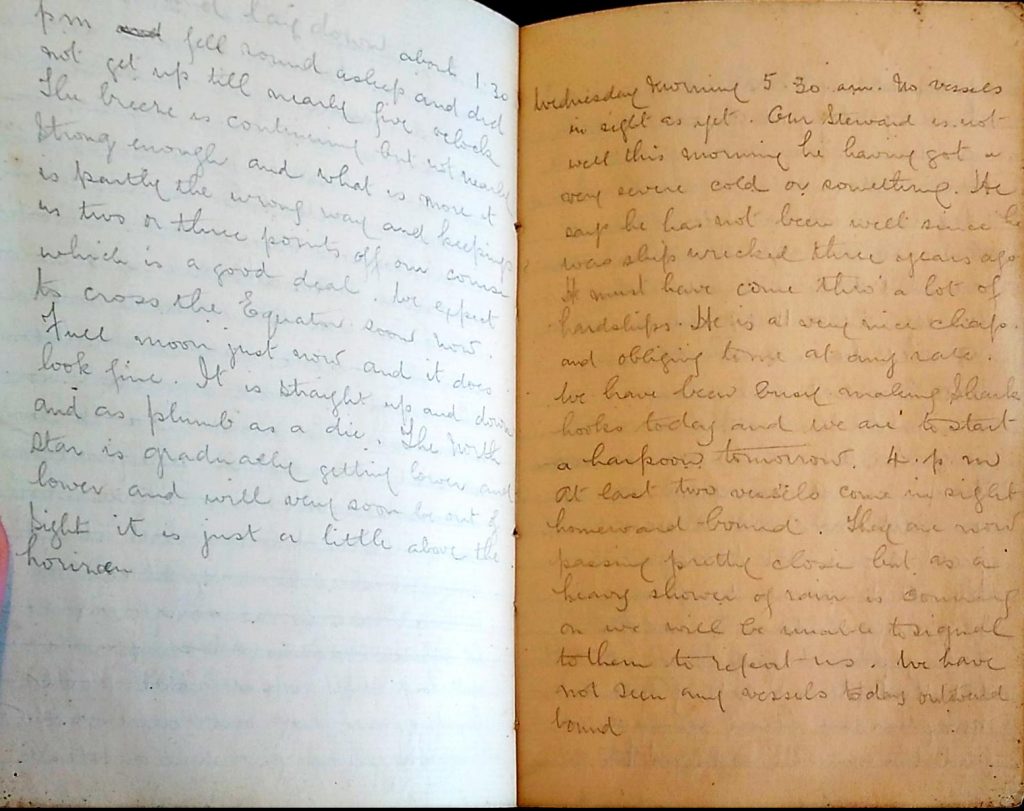

A squall draws in and the weather worsens. The men are thankful of the cooling rain and its sanitary value. James has a run about in a heavy shower, ‘I can tell you my feet required it’. We are given further details of the conditions on board and just how arduous the toll of such a journey must have often been. Also, the first mention of illness with a fellow passenger, Kydd, waking James through the violence of his fits. ‘He never knows when he has them and will scarcely believe it when you tell him’. It is of course impossible to accurately diagnose the illness but the reality of life aboard again seeps from the pages of the diary. James also mentions that the Steward (Peter Davidson) has become unwell. Peter ascertains that this is due to him being shipwrecked three years previous. ‘He must have come through a lot of hardships’, James reflects.

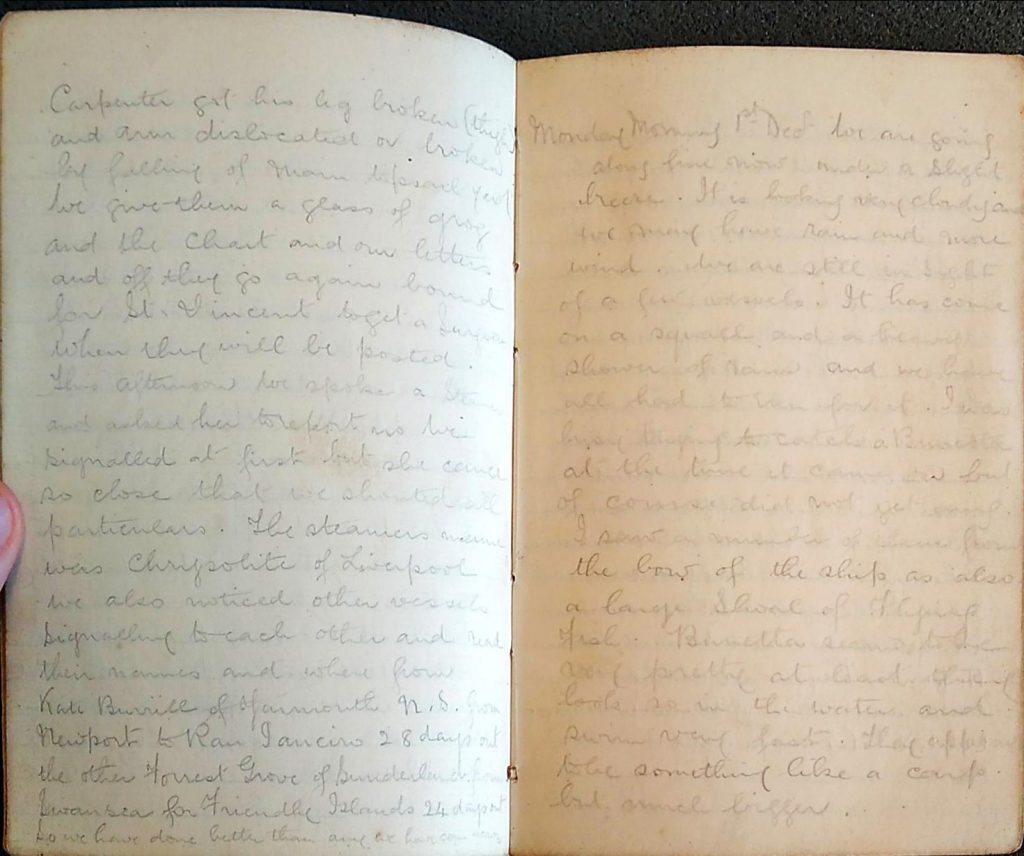

4th & 5th December

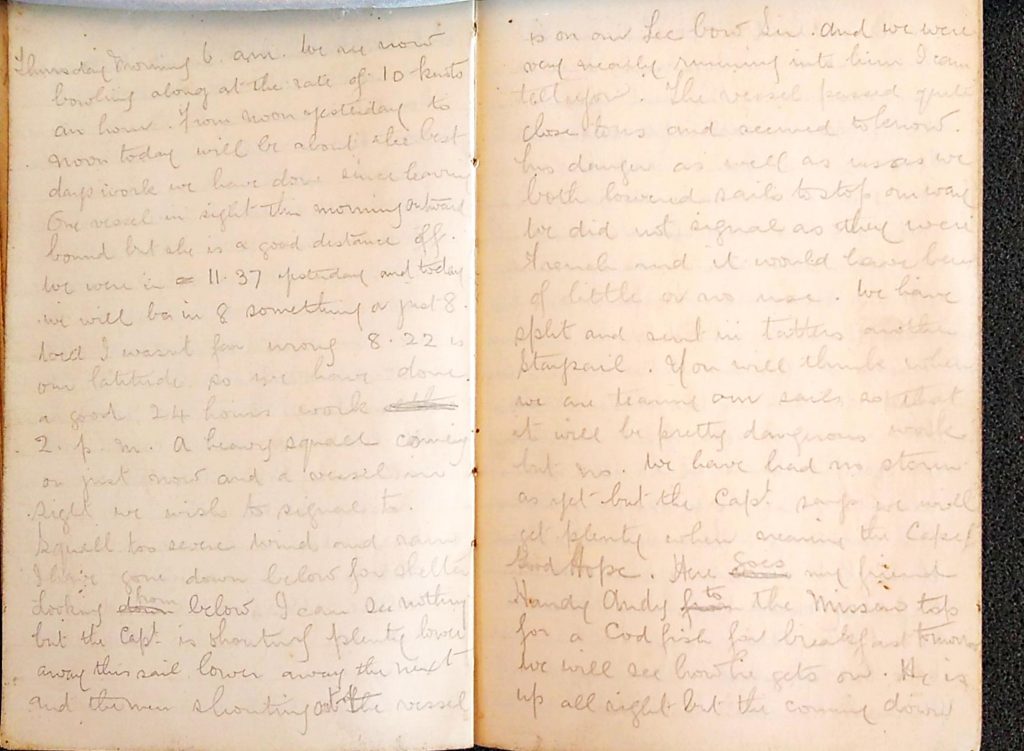

The ship is ‘bowling along at the rate of 10 knots an hour’ in a good run but is later disrupted by further bad weather and a near collision with another ship. James declares, ‘I have gone down below for shelter. From below I can see nothing, but the Captain is shouting plenty, lower away this sail, lower away the next, and the men shouting the vessel is on our lee bow Sir and we were very nearly running into him I can tell you’. A vivid image of a near crisis on rough seas. The Captain (R King) warns of the forthcoming storms to expect near the Cape of Good Hope and talks of the plague of flies he encountered in Ismailia, Egypt.

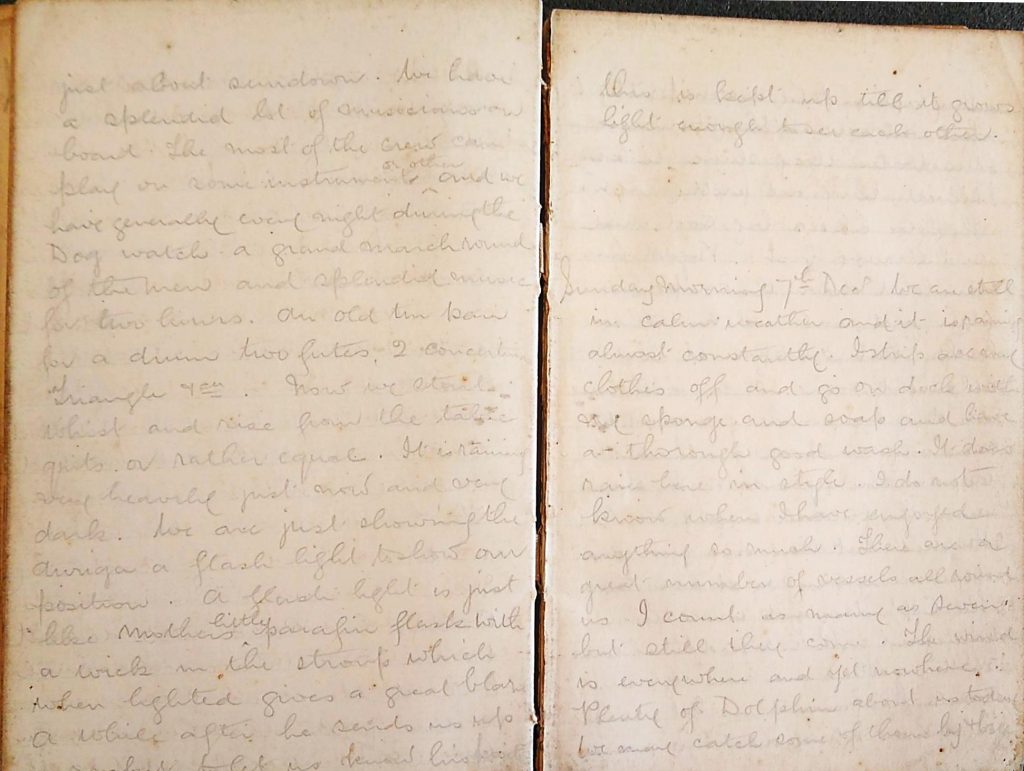

6th & 7th December

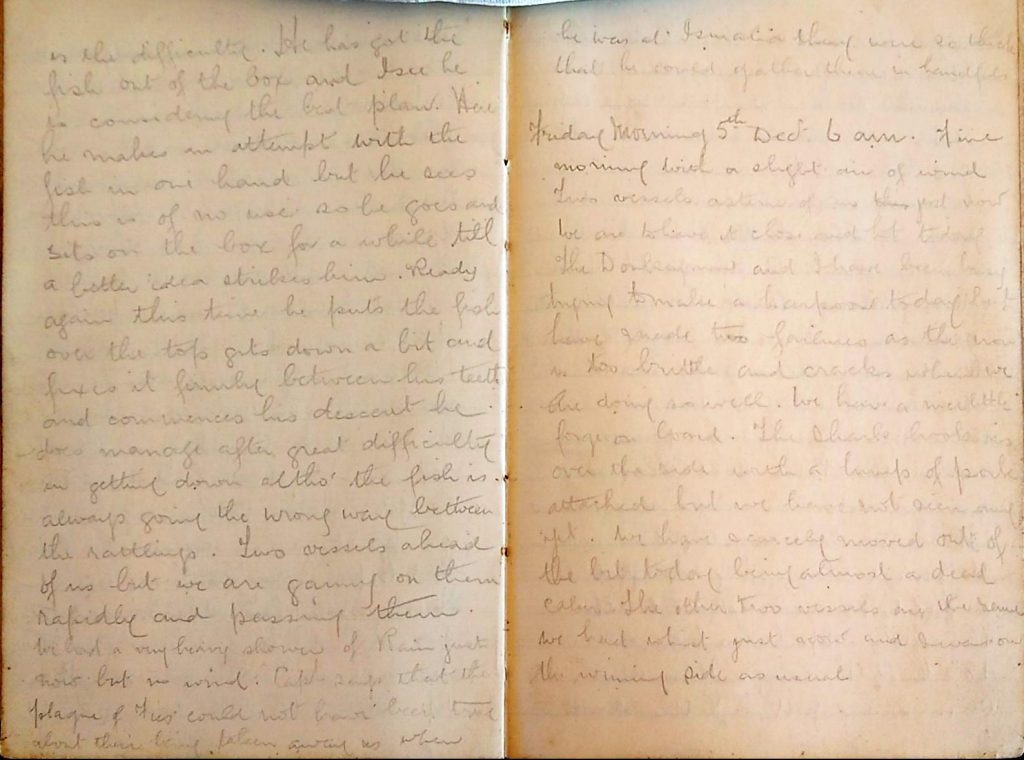

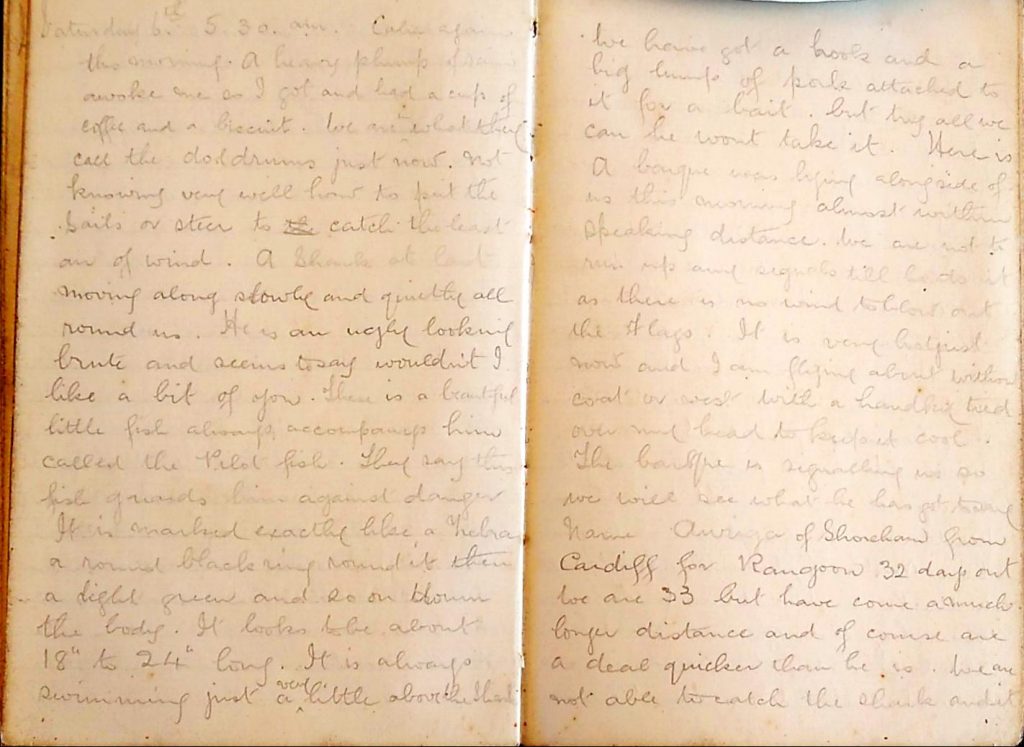

The ship finds itself in the calm seas of ‘what they call the doldrums’ or the ITCZ (Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone). Here, within five degrees north or south of the equator, the intense solar heating forces the air to circulate in an upward direction often becalming sailing ships for weeks on end: hence, the doldrums. A shark circles the ship, an ugly brute who ‘seems to say wouldn’t I like a bit of you.’ The men are trying to catch it with pork on a hook. There is no wind to blow out the flags to signal other ships. Onboard the crew and passengers pass time playing music, ‘an old tin pan for a drum, two flutes, two concertinas and a triangle’. The weather stays calm, but it rains almost constantly. James takes the opportunity to ‘strip all my clothes off and go on deck with my sponge and soap and have a thorough good wash’. He continues ‘I do not know when I have enjoyed anything as much’. His high spirits are heartening. The calm winds mean that ‘there are now eighteen vessels lying around us’. We can imagine the ships sat stagnant in the hot equatorial weather, waiting to continue their journeys. James’ friend Handy Andy finds a note from his daughter in his chest ‘come home again soon dear Father’ and breaks down in tears.

8th December

Rats keep James up at night and sharks follow the vessel. It is ‘hotter than ever’ but a steady breeze is pushing them along nicely. James continues his winning streak at whist, ‘the Captain says it is the cards but no it is good play’.

9th & 10th December 1884

More hot weather and a lack of north east trade winds becalms the vessel again, ‘we may be a long time yet’, James bemoans. They spot another vessel headed for Singapore, ’36 days out having had a very tedious passage’. The sheer length of time aboard starts to become apparent, James now having been at sea over a month. However, he stays positive mentioning further heavy rain that fills ‘every available barrel on board’, a ‘splendid supply of water for washing purposes’. Even the pigs are let out to wash. The constant downpour, the becalmed vessel, the pigs running about aboard, thousands of miles from home and land, James’ experience is potent. The Captain continues to lose at whist and leaves in a huff.

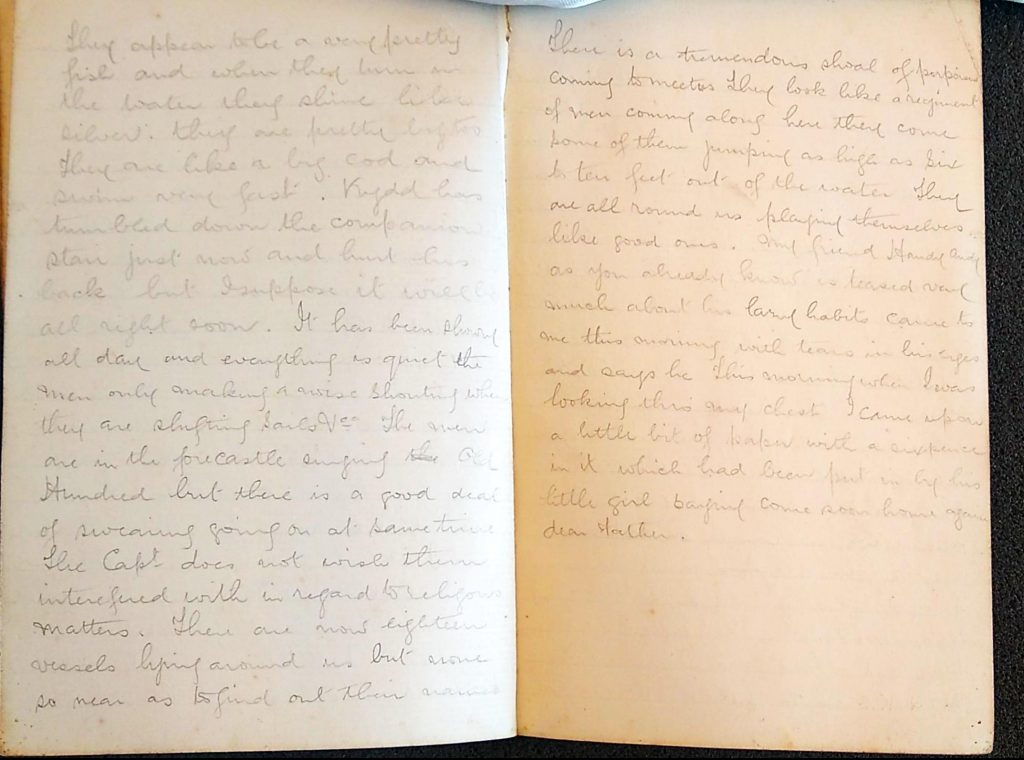

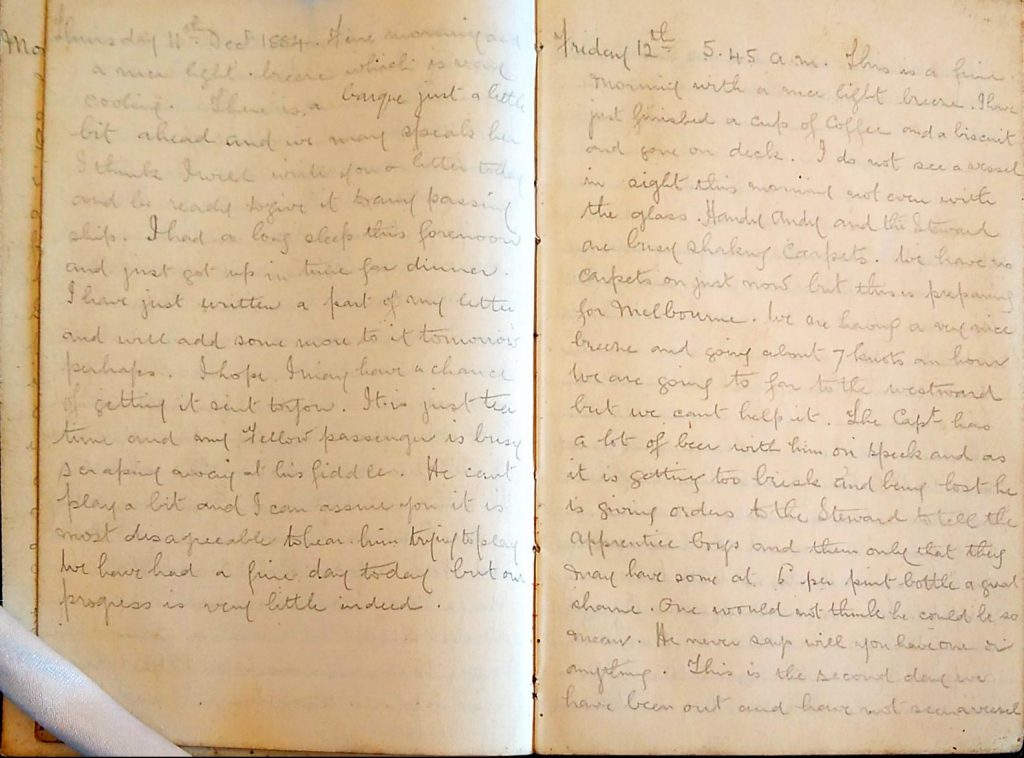

11th & 12th December 1884

‘I think I will write you a letter today and be ready to give it to any passing ship’. Who is James writing to? The narrative form of his diary seems intended for someone in particular. Perhaps Father, Mother and Liz whom he references often. A fellow passenger attempts to play the fiddle with little luck, ‘it is most disagreeable hearing him trying to play’. Perhaps the last thing you might wish for whilst adrift in the heat. Mention of coffee and a biscuit for breakfast, the Captain being mean with his stash of beer and days passing without the sight of another vessel.

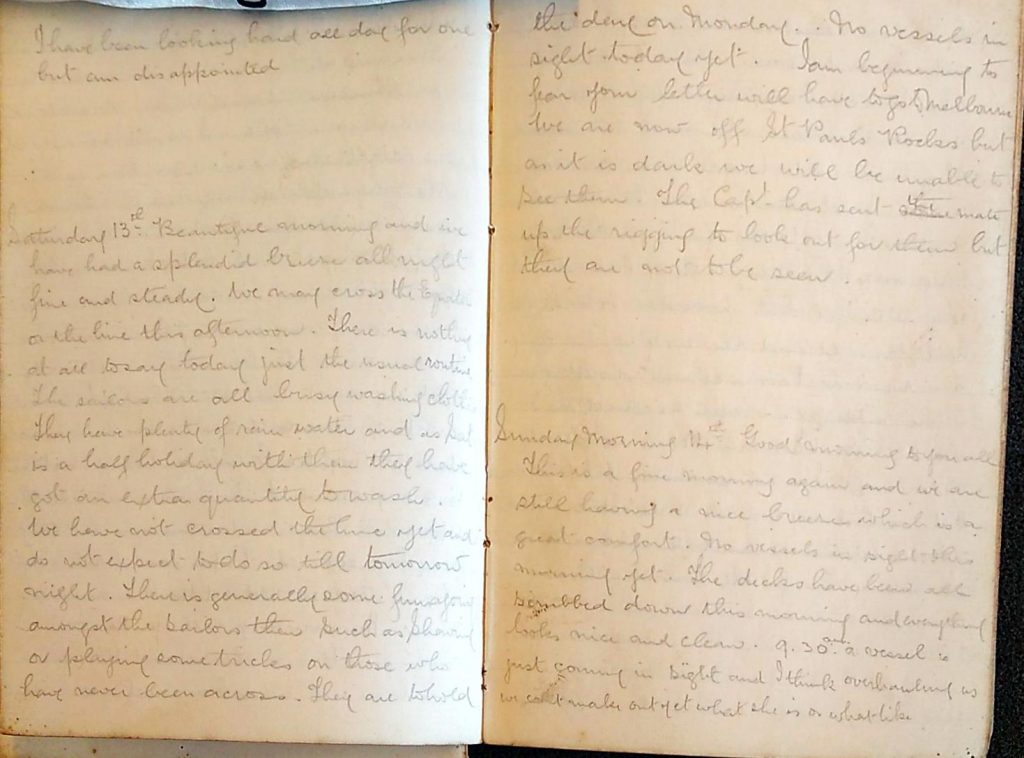

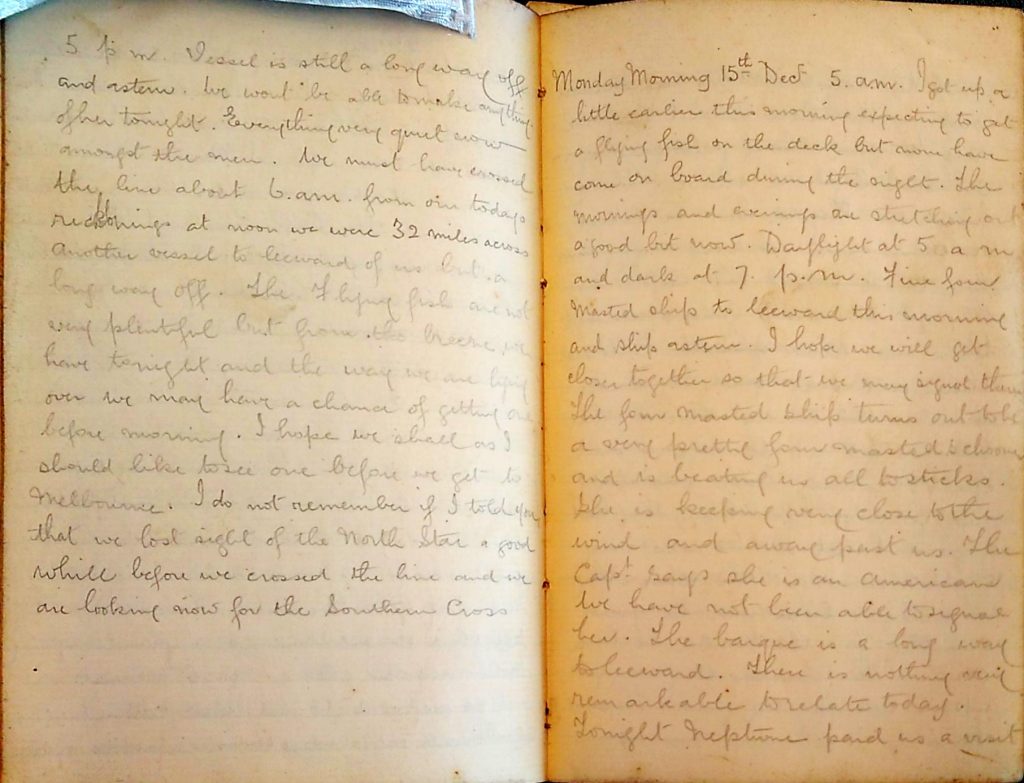

13th-15th December

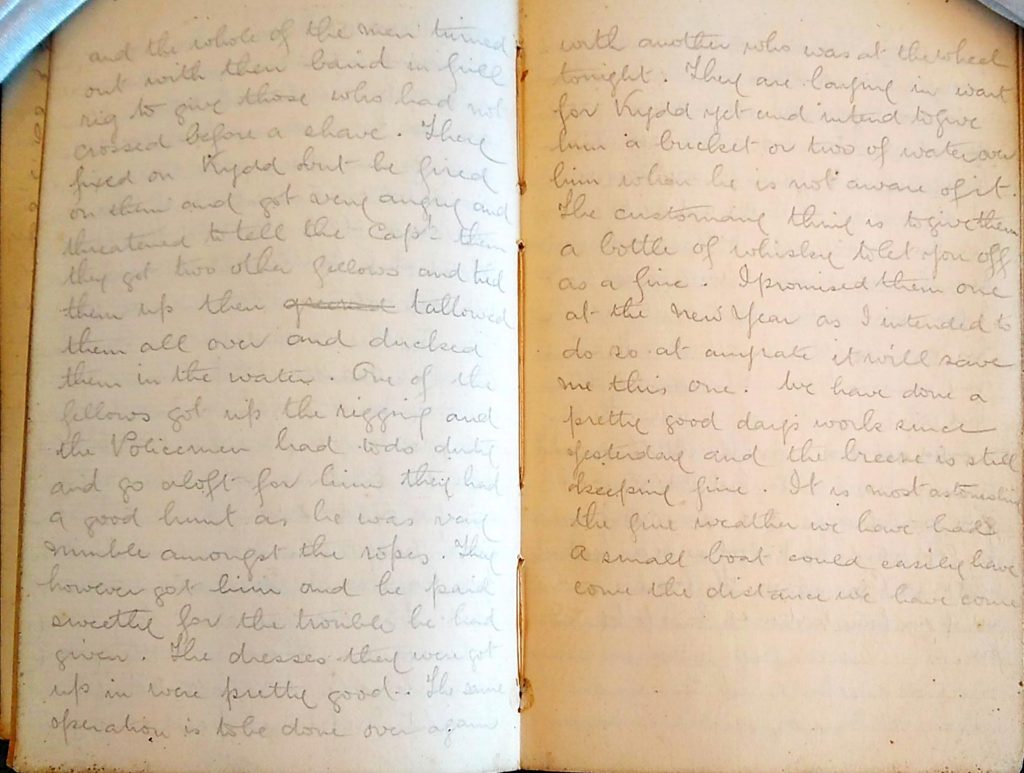

The ship passes ‘St Pauls Rocks’; the archipelago of Saint Peter and Saint Paul Rocks, a group of fifteen small islets and rocks in the central equatorial Atlantic Ocean. The Arthurstone is still passing through the ITCZ and is around 62 miles north of the equator. An event is to be held to signal the crossing of the equator when ‘there is generally some fun amongst the sailors…such as showing or playing some tricks on those who have never been across’. James later details how ‘the whole of the men turned out in their bands in full rig to give those who had not crossed before a shave…they got two other fellows and tied them up then tallowed them all over and ducked them in the water’. Having lost sight of the North Star James is now on the lookout for the Southern Cross and keen to try a flying fish if one finds its way aboard through the night. The weather is astonishingly fine. Also, mention of the policemen aboard the ship; this seems unsurprising as on a long journey like this, tempers might be expected to fray.

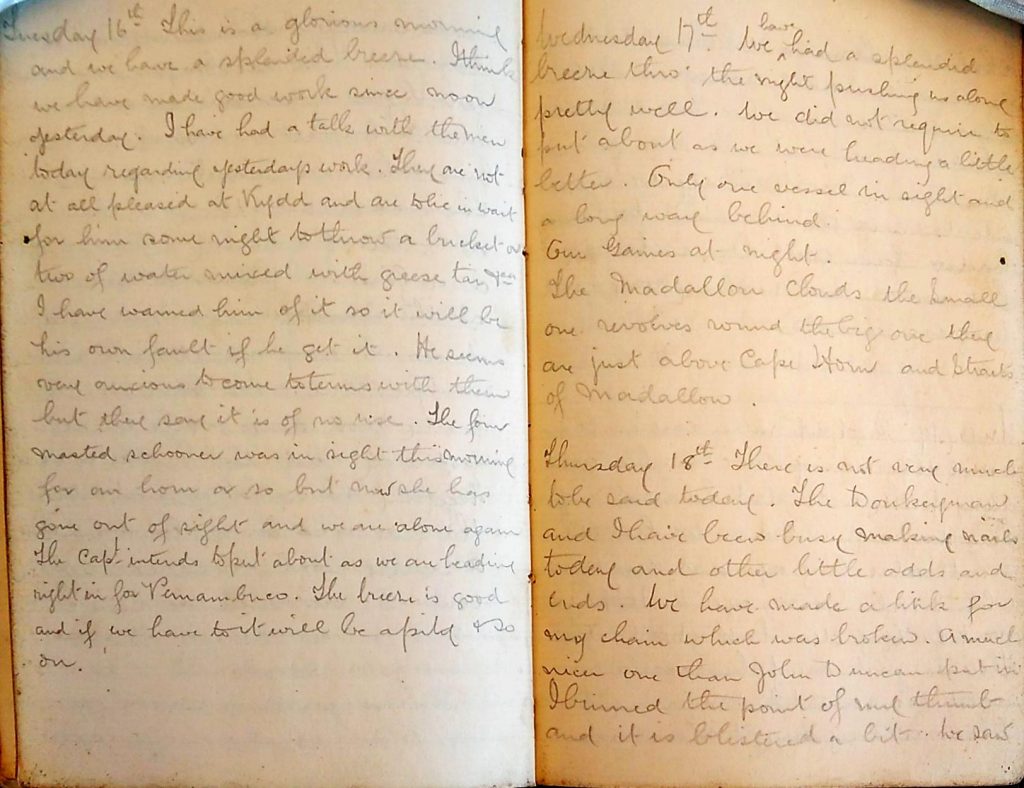

16th-19th December

‘The Captain intends to put about as we are heading right in for Pernambuco’, a state in the north-east of Brazil. More stargazing with a sighting of the ‘Madallon clouds’. This is almost certainly a misspelling a Magellan as he refers in the next line to ‘Cape Horn and the Madallon Strait’. The Magellanic Clouds are two irregular dwarf galaxies visible in the southern hemisphere. They are members of the Local Group and are orbiting the Milky Way galaxy. This must have been an amazing sight, ‘the small one revolves round the big one’. It is too easy today, with Google and other resources, to dismiss the importance of such one-off experiences and the lingering impact they would have had on a person’s reality. There is more music and dancing aboard, ‘the band turned out six strong’.

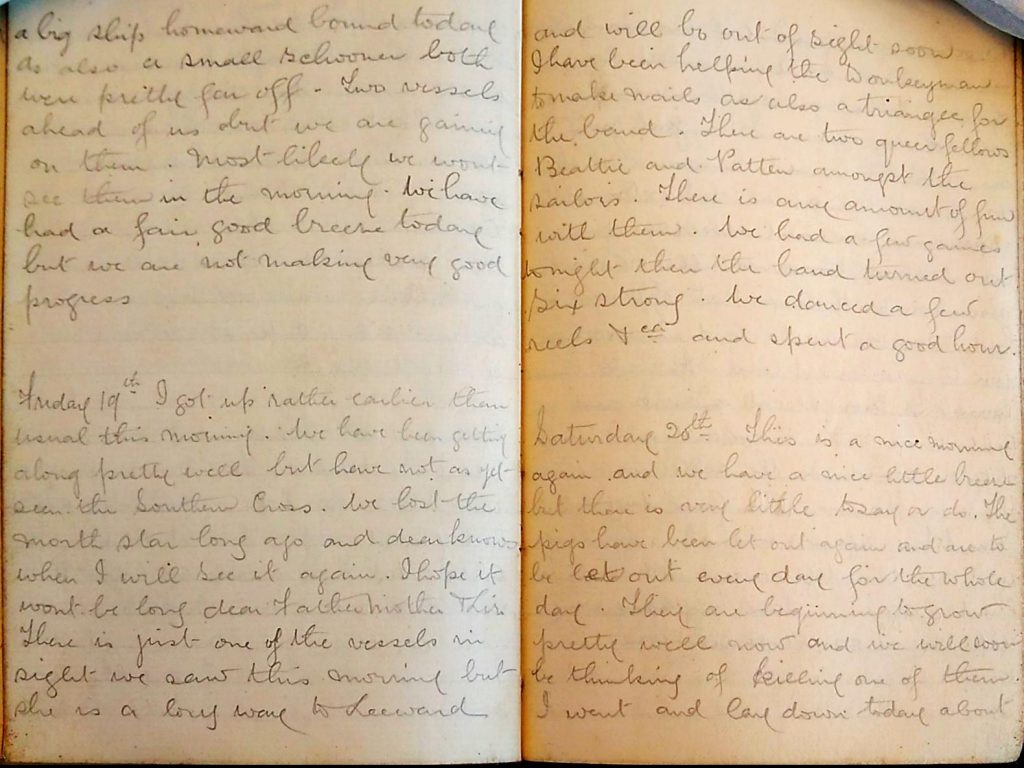

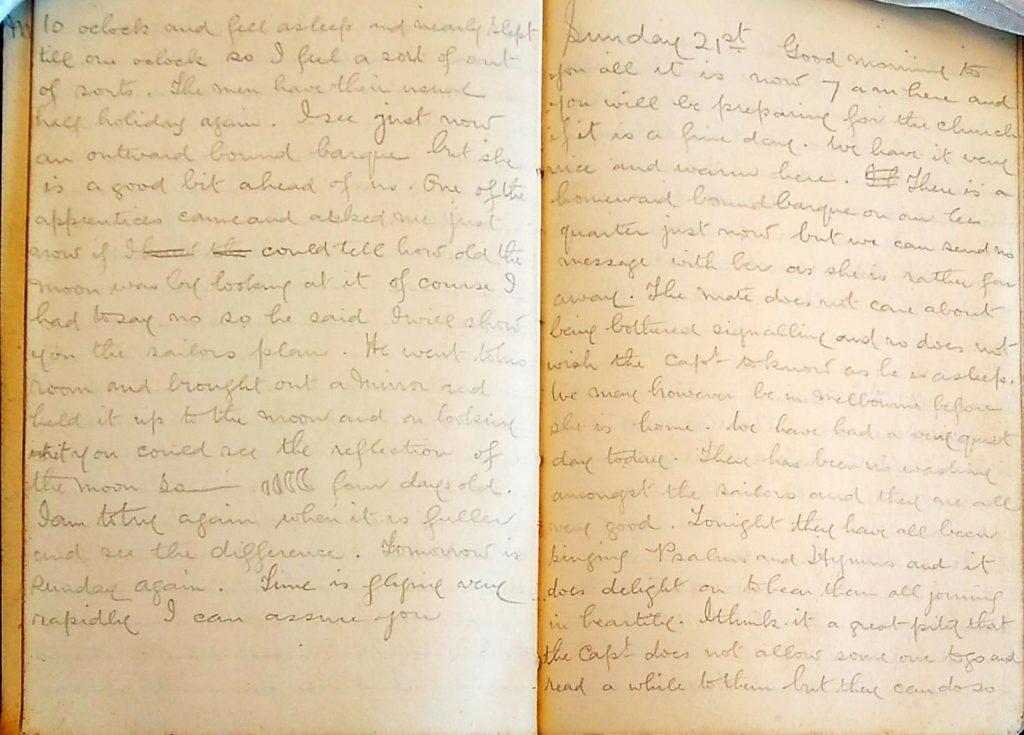

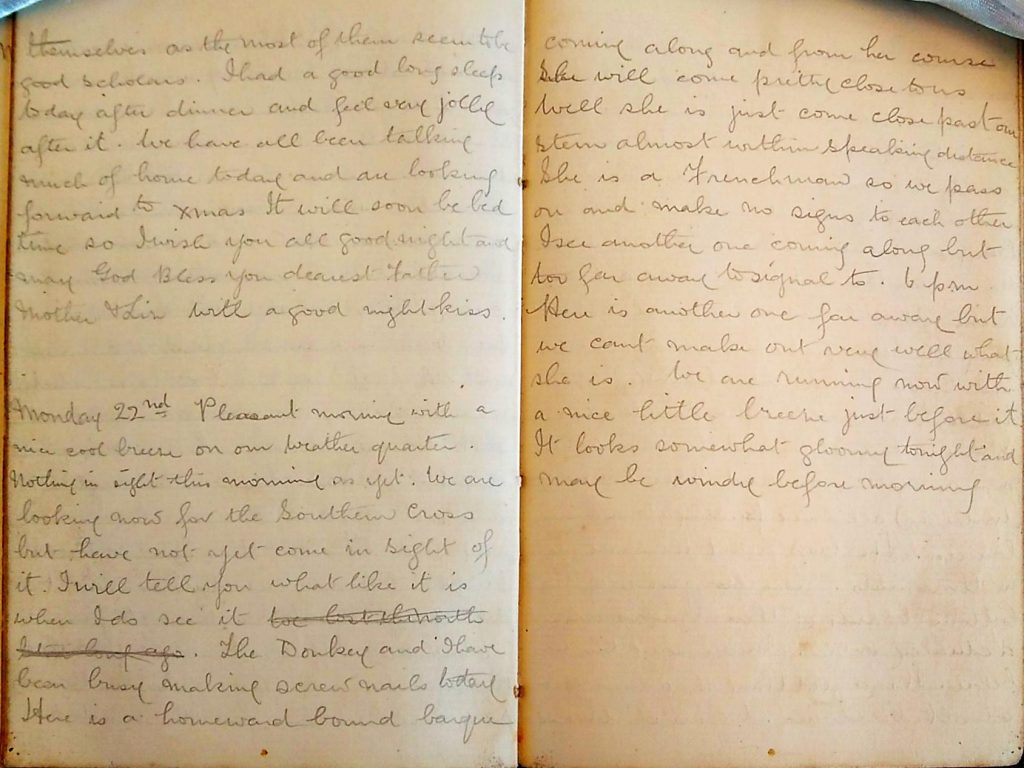

20th-22nd December 1884

The pigs are let out again and are growing well, ‘we will soon be thinking of killing one of them’. A sailor aboard shows James with a mirror how to tell how old the moon is. Look for his drawing within the text, the moon ‘four days old’. The length of the voyage seems not to bother James, ‘time is flying very rapidly I can assure you’. His narrative style continues as he thinks, ‘you will be preparing for church if it is a fine day’. Psalms and Hymns are sung. ‘God Bless you dearest Father, Mother and Liz with a goodnight kiss’. James continues to search for the illusive Southern Cross.

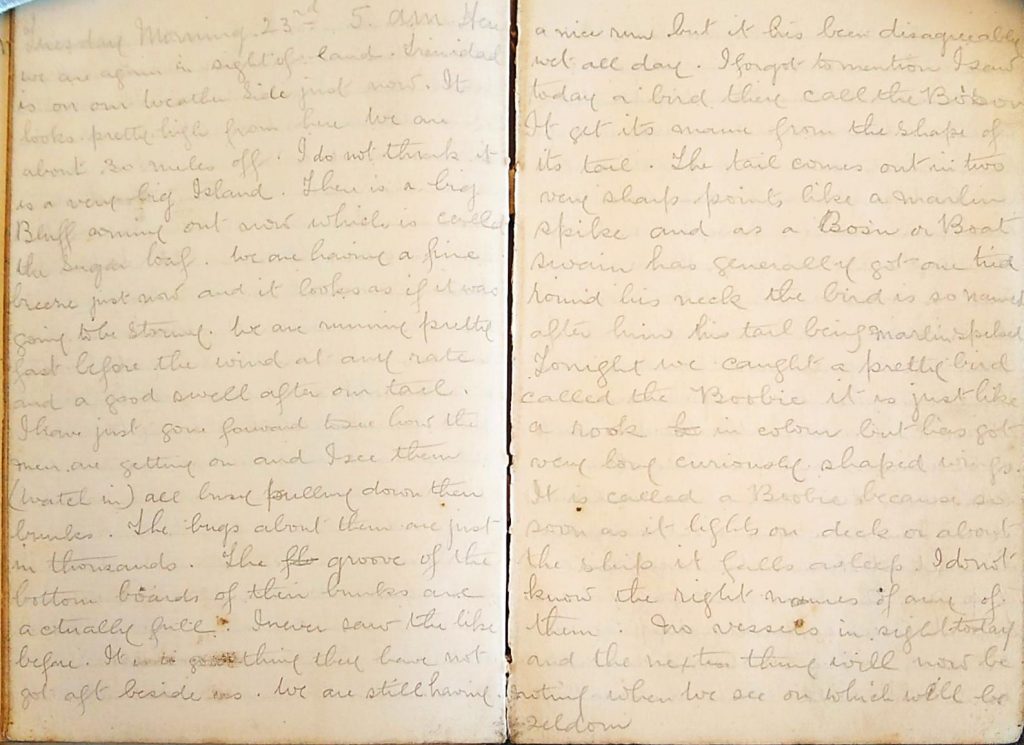

23rd & 24th December 1884

James spots two new birds, the ‘Boson’ and the ‘Boobie’. Christmas Eve arrives and ‘the starboard watch turn out with their musical instruments and have a march past the cabin door three or four times to see if the Captain will open his heart and give all hands a glass of grog’. Thankfully he submits, ‘how they run and the picture of glee on every face’.

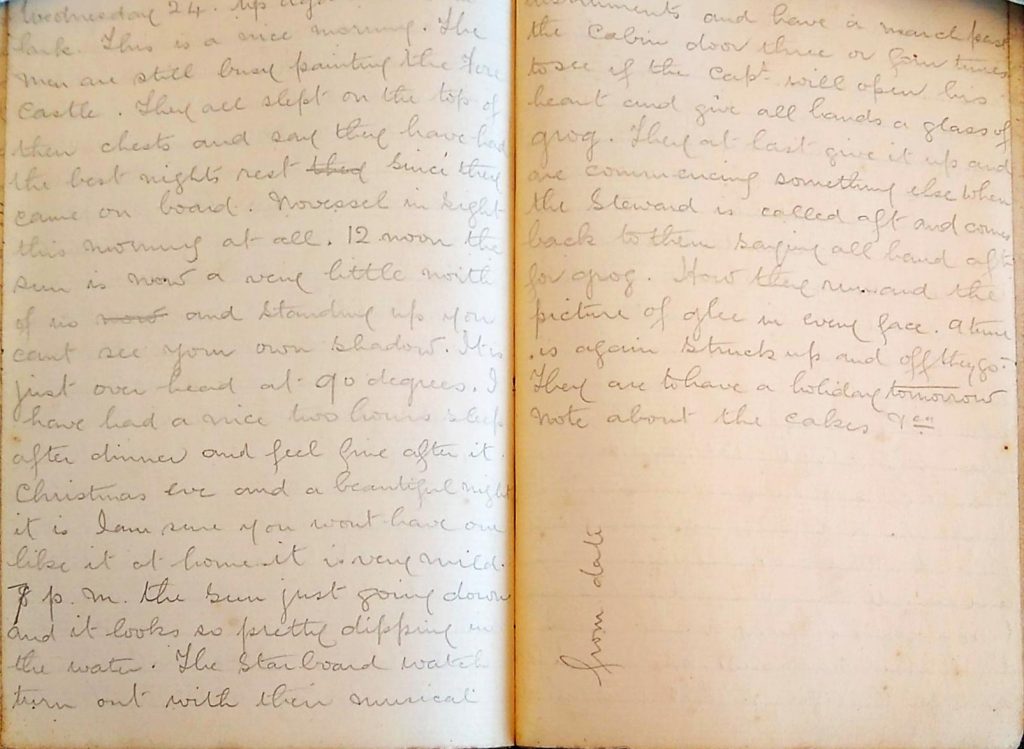

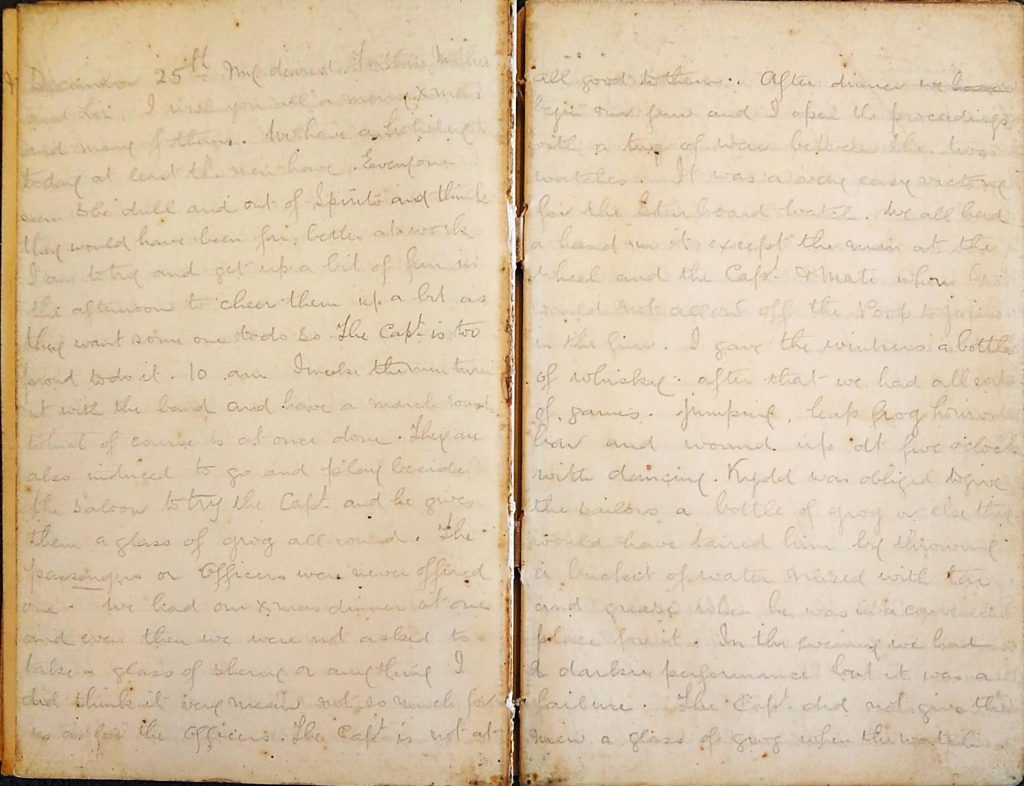

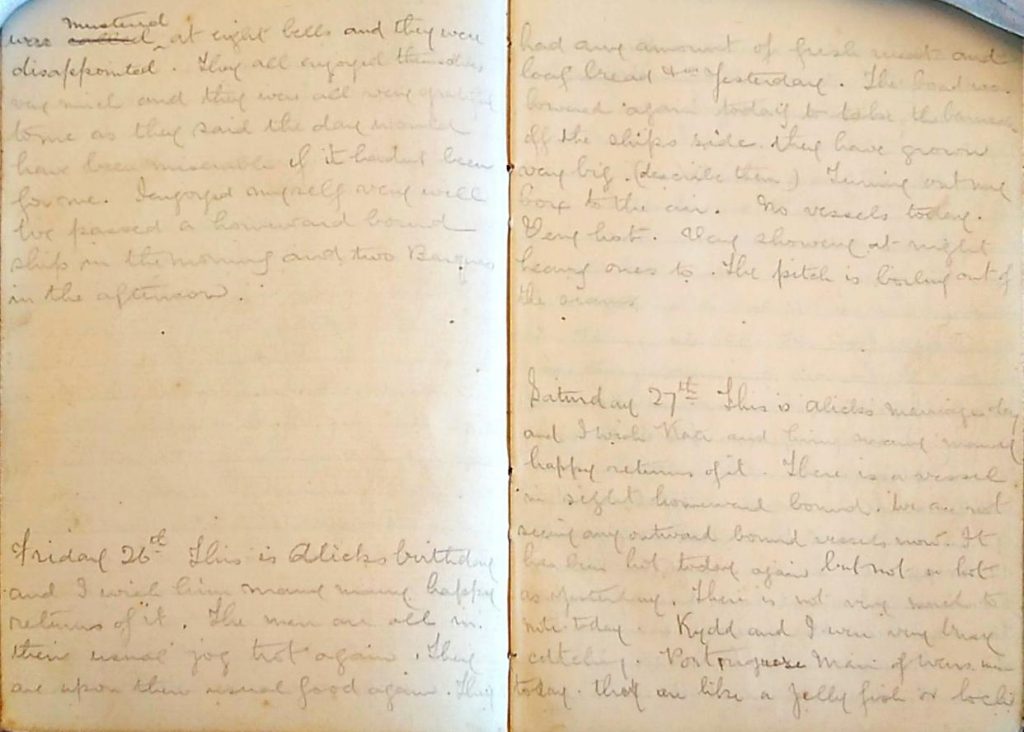

25th-28th December 1884

‘My dearest Father, Mother and Liz, I wish you a merry Xmas and many of them’. James is recruited to lift the spirits of the men who seem dull and organises the band to march and play in the hope of another glass of grog for the men. Also, a tug of war between the two watches onboard sees the starboard watch the victors. James gives the winners a bottle of whisky, again suggesting that he is a notable passenger and someone of some wealth. Mention of a ‘darkie performance’ is unsettling amongst the obvious good cheer of the day and jolts one to the hidden racial reality decidedly absent until now in the words of the diary. The hot weather continues and Alick celebrates both his birthday and wedding to Kate onboard. James and Kydd fish for Portuguese Man o’ War. James has a strong argument with the Captain regarding ‘the Scotch’.

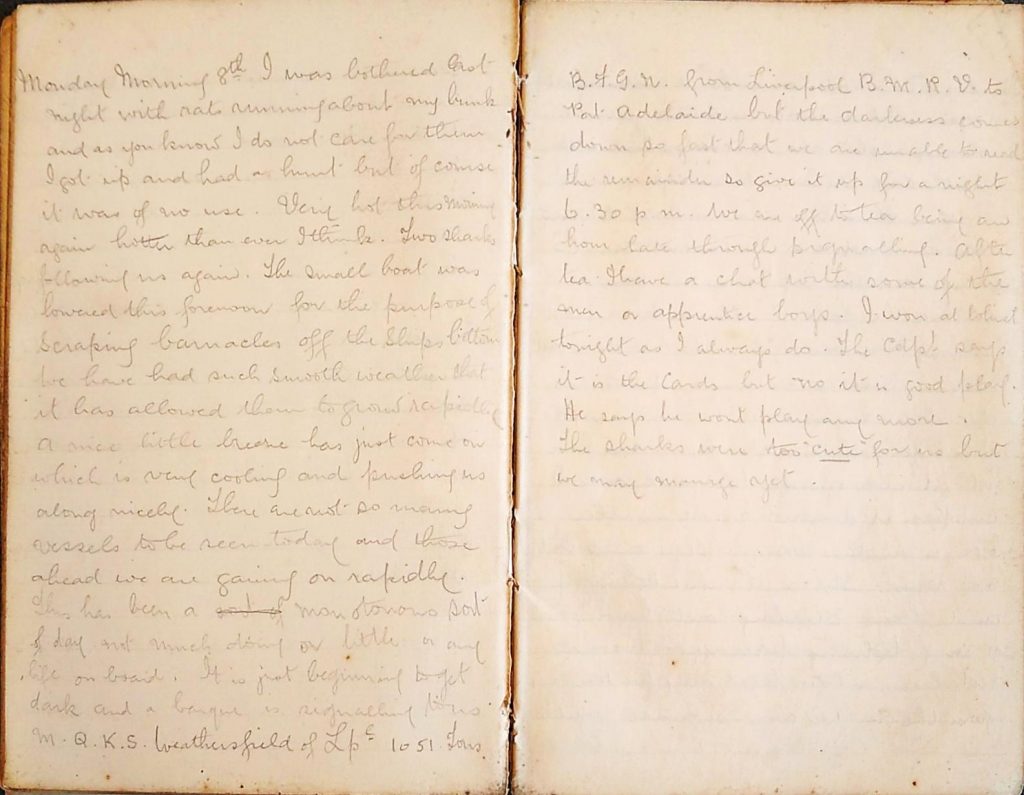

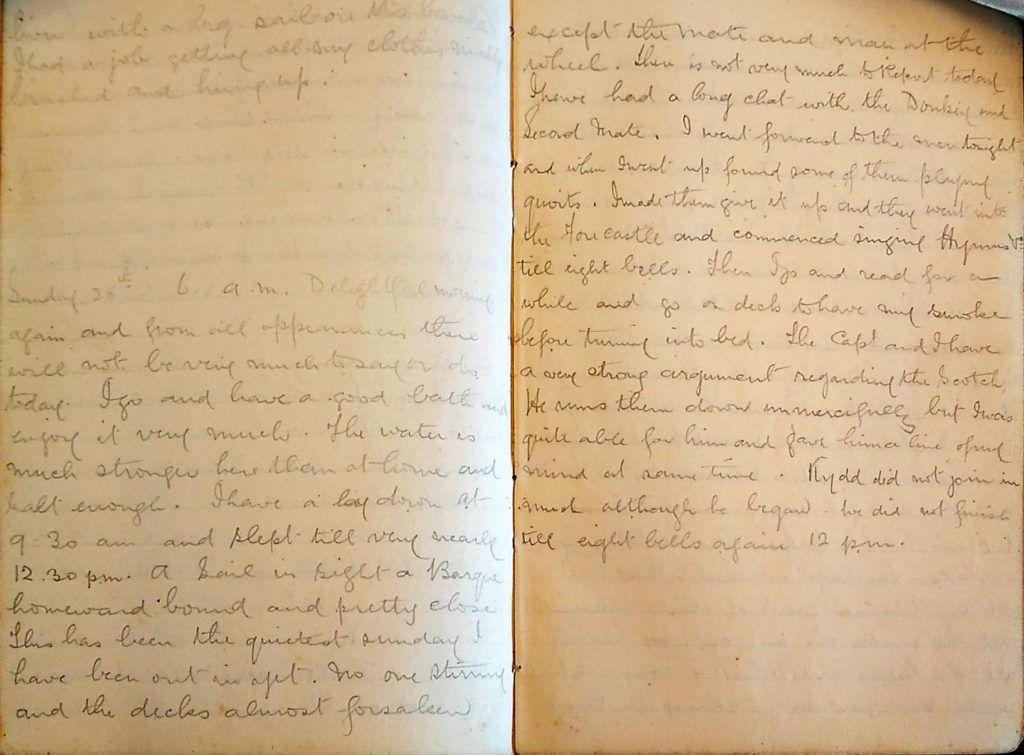

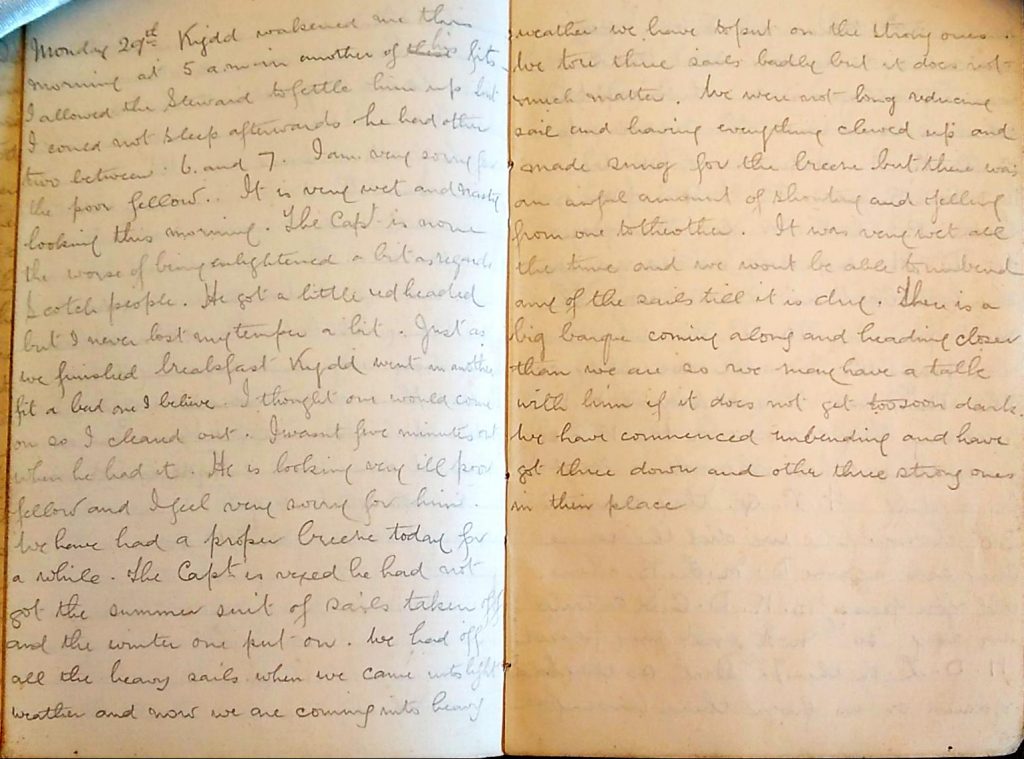

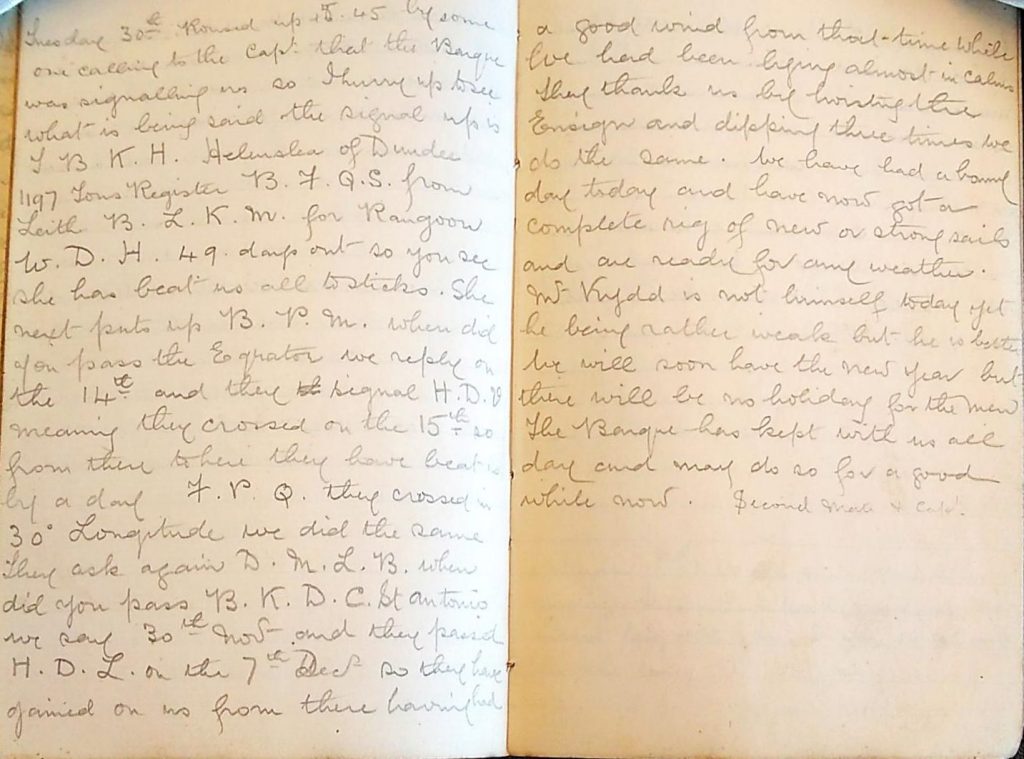

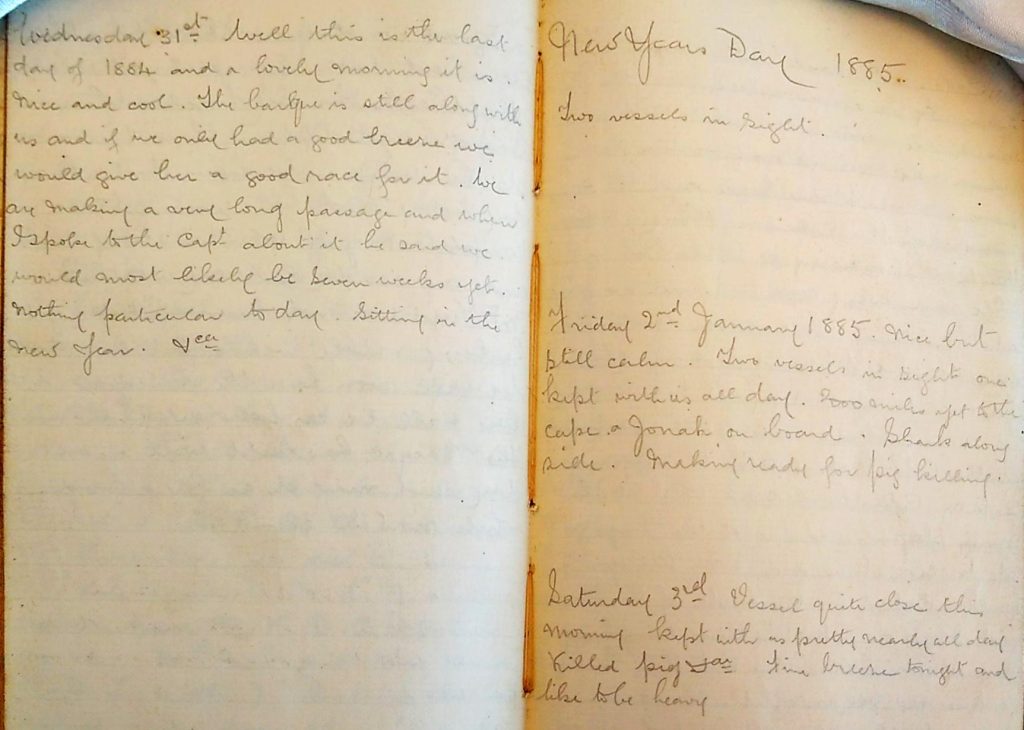

29th December 1884 – 3rd January 1885

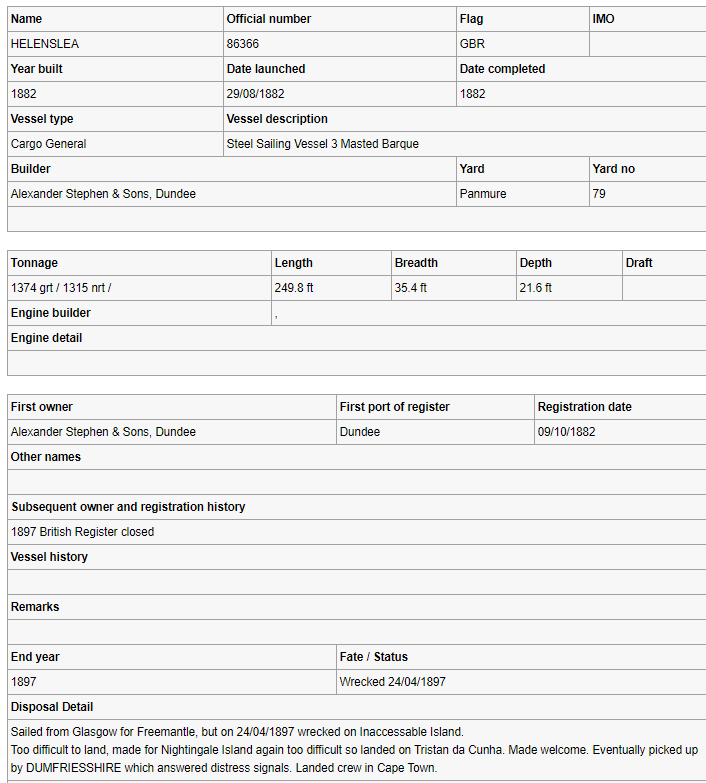

Kydd suffers more fits and is ‘looking very ill poor fellow’. The weather starts to turn and the heavy sails replace the light ones amidst ‘an awful amount of shouting and yelling’ and heavy rain. Signalling with the Helenslea of Dundee (further information below), another barque headed for Rangoon from Leith, who is making better time than the Arthurstone. The Captain reckons they will be seven weeks yet to Melbourne. The New Year passes with little mention in the diary. Sharks continue to follow the vessel and a pig is killed.

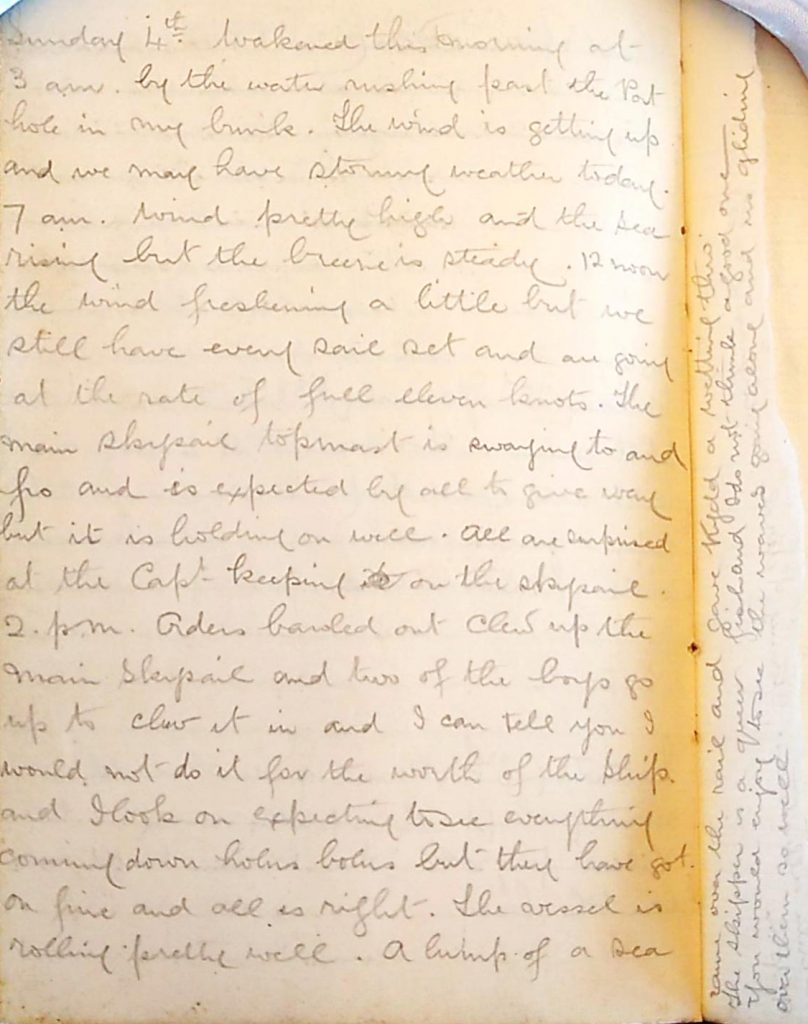

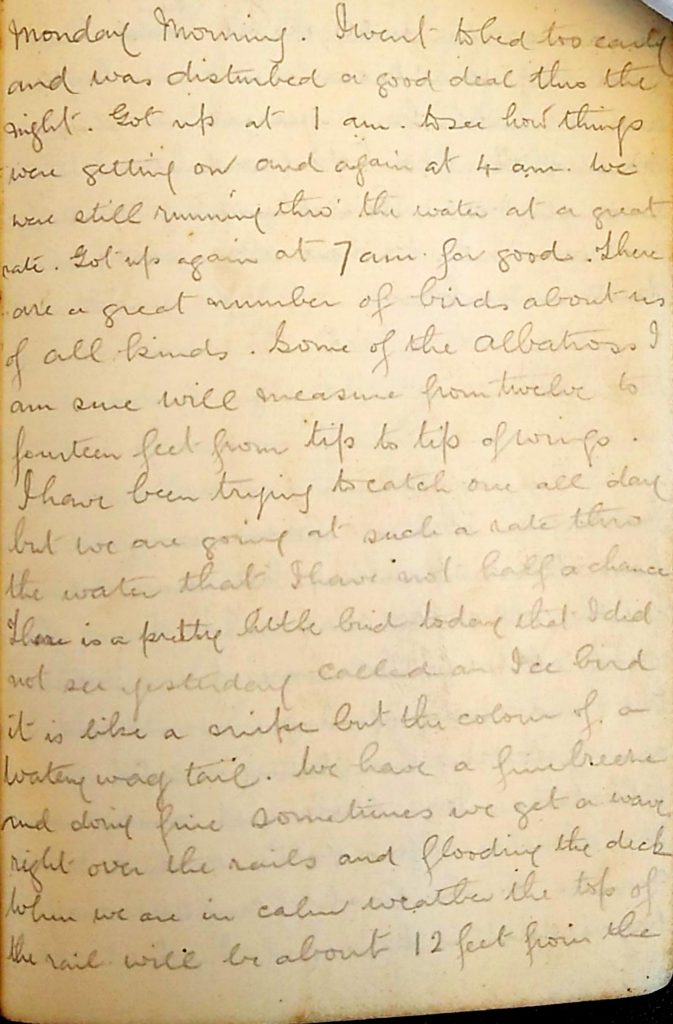

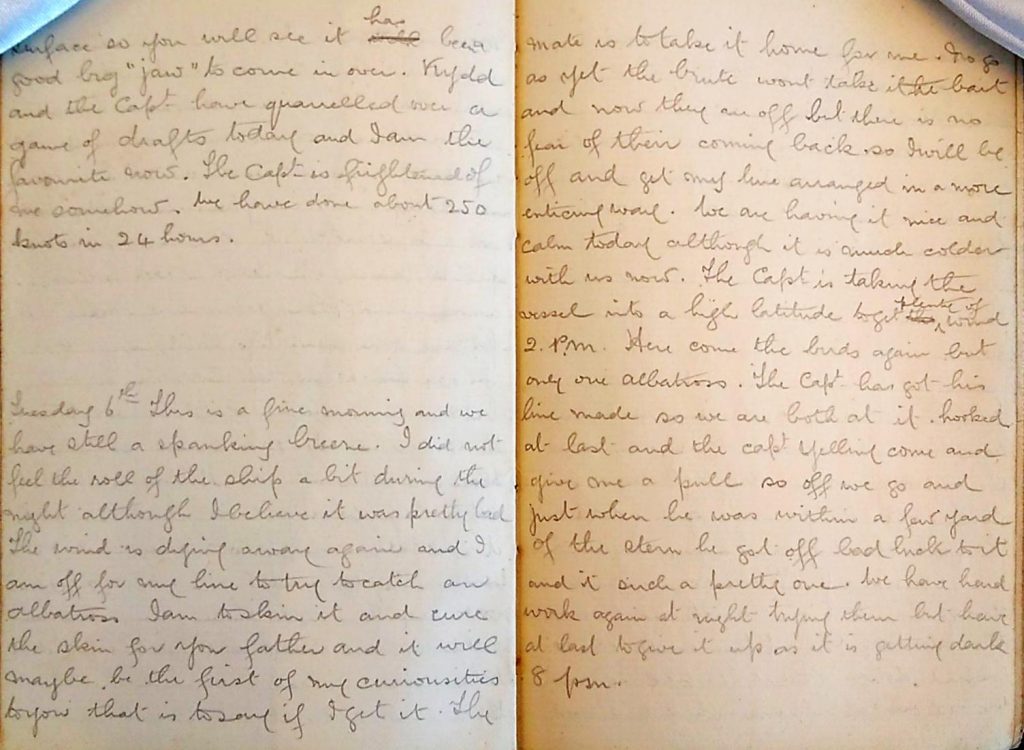

4th-6th January 1885

‘Wakened this morning at 3am by the water rushing past the port hole in my bunk’. The weather continues to worsen however the wind has picked up and the ship is moving along ‘at the rate of full eleven knots’. Pages have been ripped out of the diary and the end of the entry for the 4th of January is written on the remains. However, no entries are missing here, and the pages must have been used for another purpose. A great number of birds are around the ship including albatrosses ‘I am sure will measure from twelve to fourteen feet from tip to tip of wings’. James is trying to catch one so that he may ‘skin it and cure the skin for you father’. On the menu is ‘potted head’, a meat jelly.

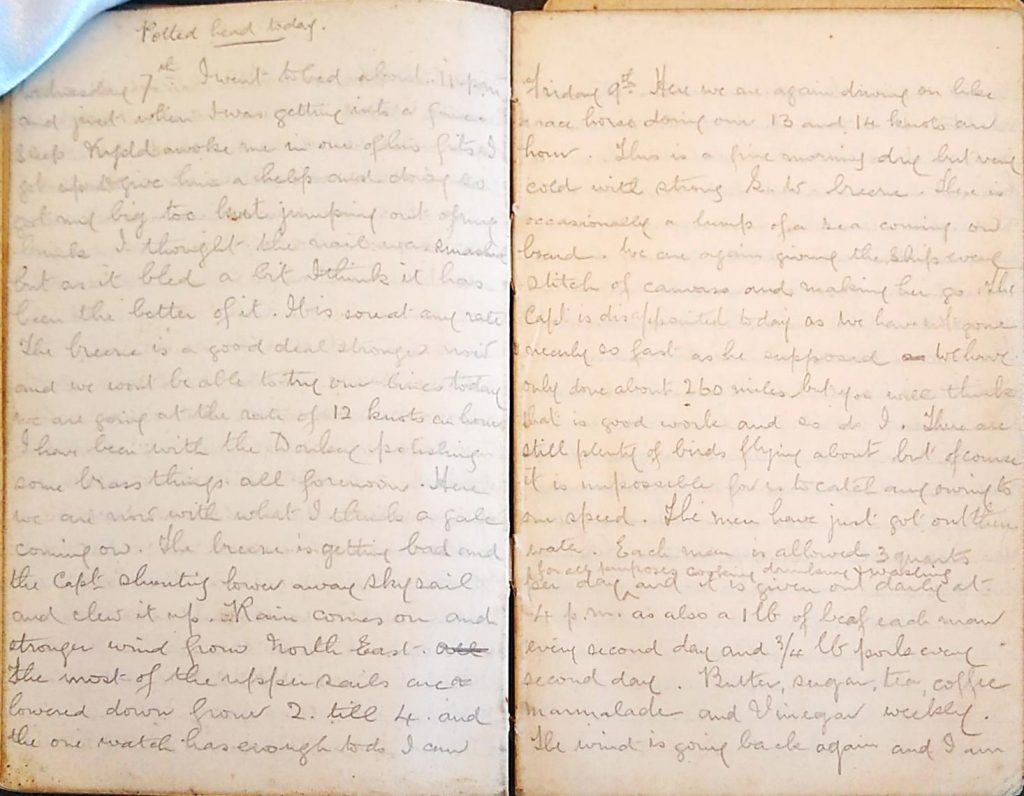

7th-11th January

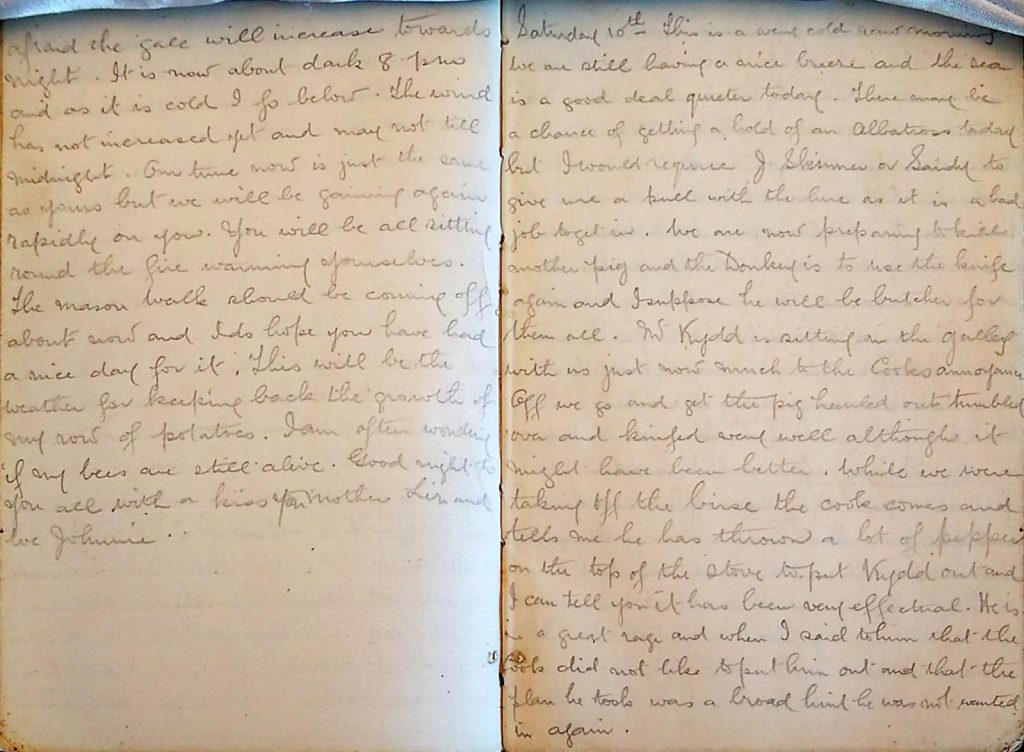

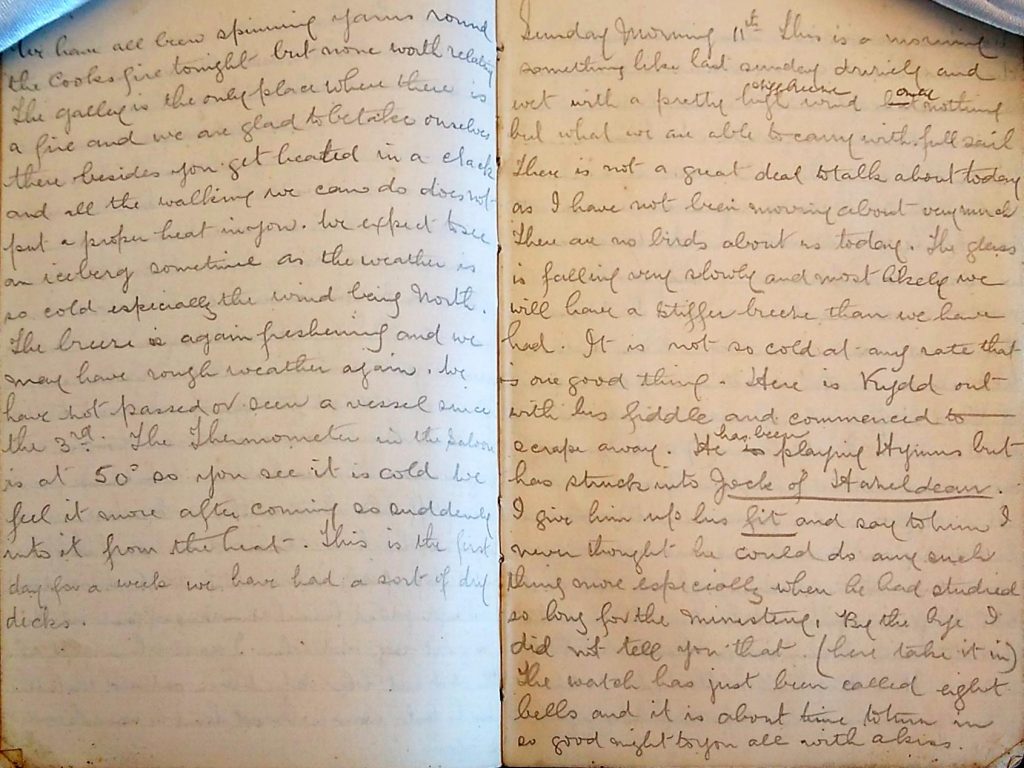

Kydd has further fits throughout the night and James smashes his big toe on a nail getting up to try and help. The vessel is now ‘driving on like a racehorse’ in the stronger winds and the temperature has dropped further. The Captain is disappointed with them only having done ‘about 260 miles’ in one day showing just how fast they are moving along. A run down of the food allowance on board is given, ‘each man is allowed three quarts a day [water] for all purposes, cooking drinking and washing and it is given out daily at 4pm as also a 1lb of beef each man every second day, ¾ lb pork every second day. Butter, tea, coffee, vinegar, marmalade weekly’. More kisses goodnight to mother Liz and wee Johnnie as James ruminates on ‘my row of potatoes’ and ‘my bees’ back home. The weather has turned so cold that James expects to see an iceberg soon and the nights are spent ‘spinning yarns’ round the cook’s fire.

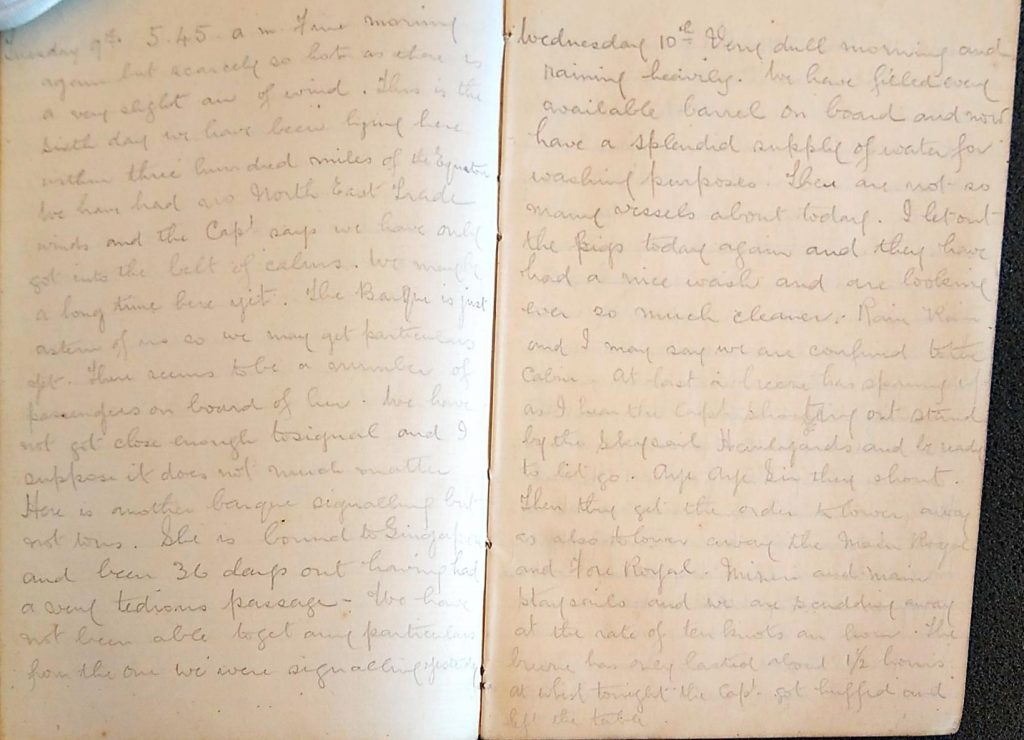

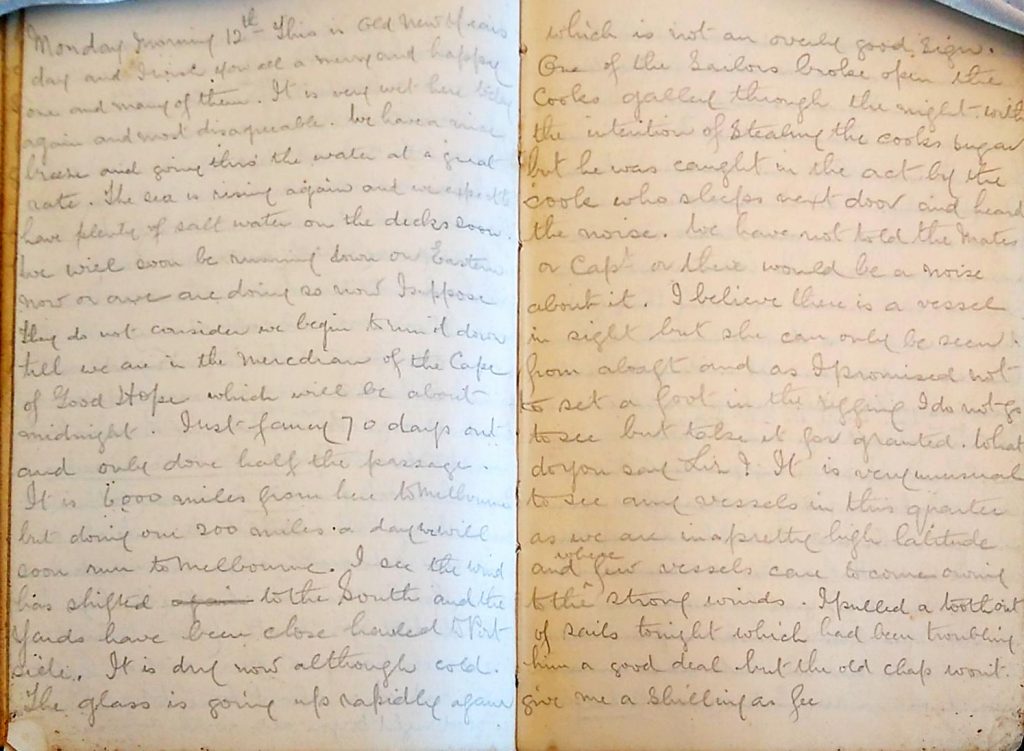

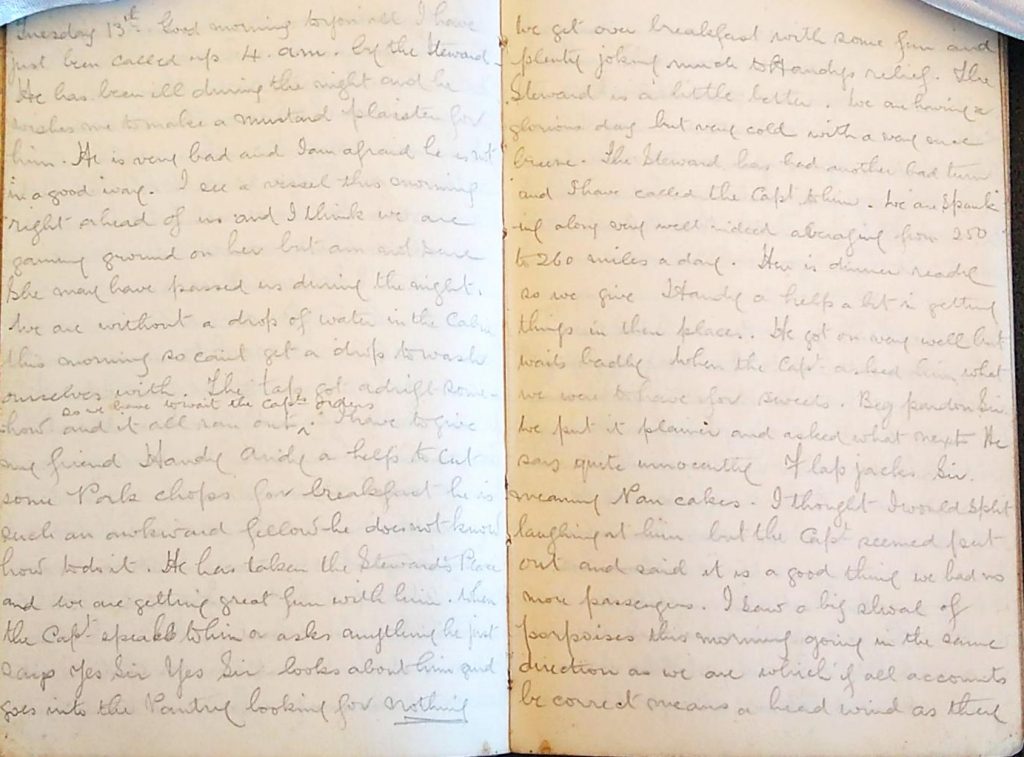

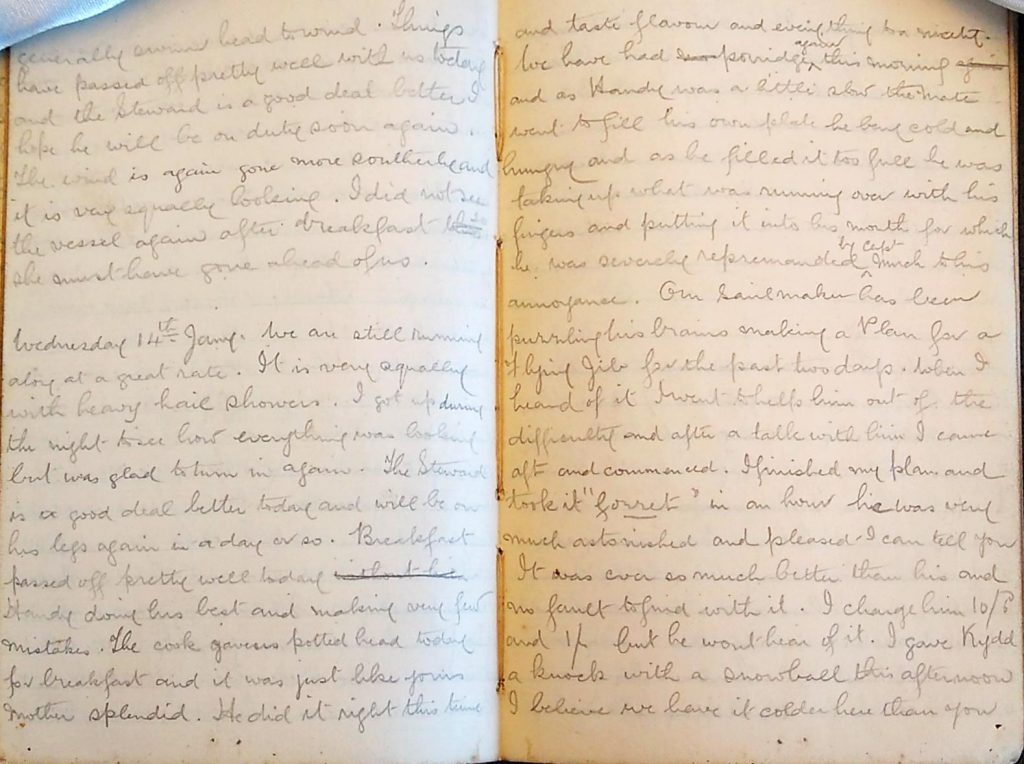

12th-14th January 2020

‘Just fancy, seventy days out and only done half the passage. It is six thousand miles from here to Melbourne’. James wishes the reader a ‘merry and happy’ old New Year’s Day which would traditionally have fallen on the 13th of January, going by the Julian calendar. They continue to move along quickly, and he hopes to be at their destination soon. James reports taking care of others on board. He pulls out a fellow passenger’s tooth ‘which had been troubling him a good deal, but the old chap won’t give me a shilling as a fee’ and makes a mustard plaster for the Steward. James spots more porpoises, albatrosses and has another meal of potted head ‘just like yours mother, splendid’. Handy Andy’s comic relief is a source of great fun and solace amidst harsher conditions, ‘Good night to you all. My feet are very cold’.

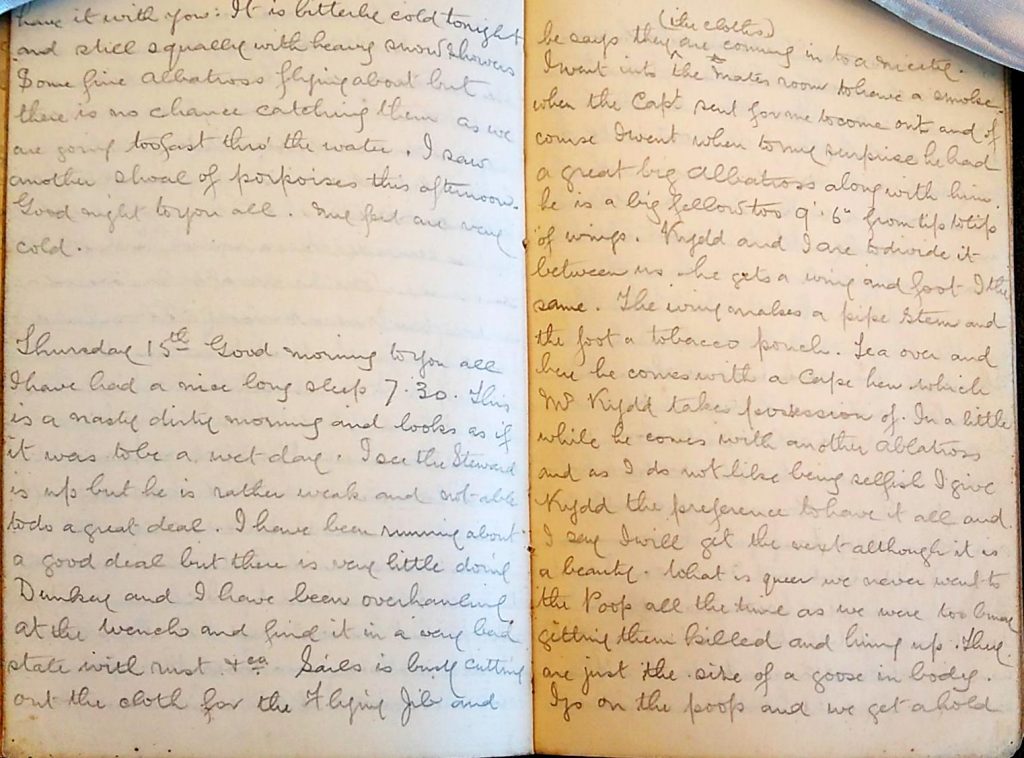

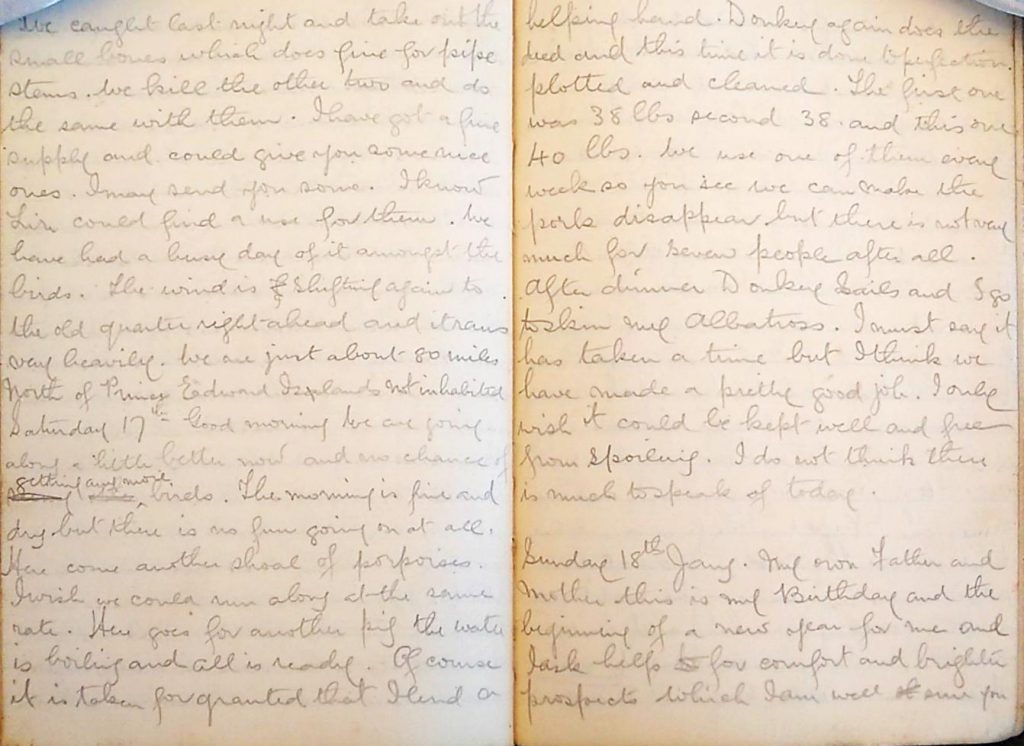

15th-18th January 1885

The Captain finally catches an albatross and later so does James, ‘he is a big fellow too 9’6” from tip to tip of wings… the wing makes a pipe stem and the foot a tobacco pouch’. He plans to skin them and send one home to show just how big it is. They also hunt for mollyhawks which ‘if you only saw how it goes patter patter along just like wee John in my big boots going along the floor’. Kydd is reprimanded by the Captain for being ‘spongey’ and first to ask for every catch, ‘the Captain is wild at his selfishness and swears he won’t get another feather’. The Arthurstone is now ‘about 80 miles north of Prince Edward Island[s]’, two small islands in the subantarctic Indian Ocean, south of and belonging to South Africa. The weather continues cold and another pig is slaughtered, ‘the first one 38 lbs. Second 38 and this one 40 lbs’. The 18th ‘my own father and mother…is my birthday and the beginning of a new year for me and help for comfort and brighter prospects which I am well sure you have done also for me and surely from all that has already past and been neglected will have been punishment enough and that everything will be brighter for the future’.

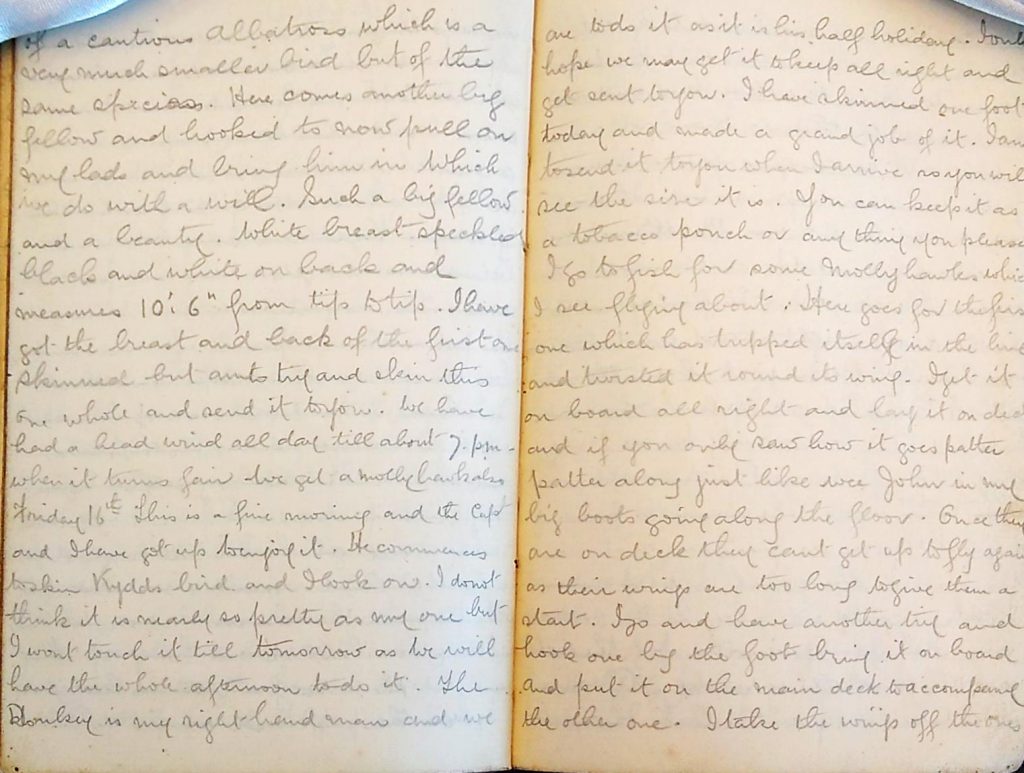

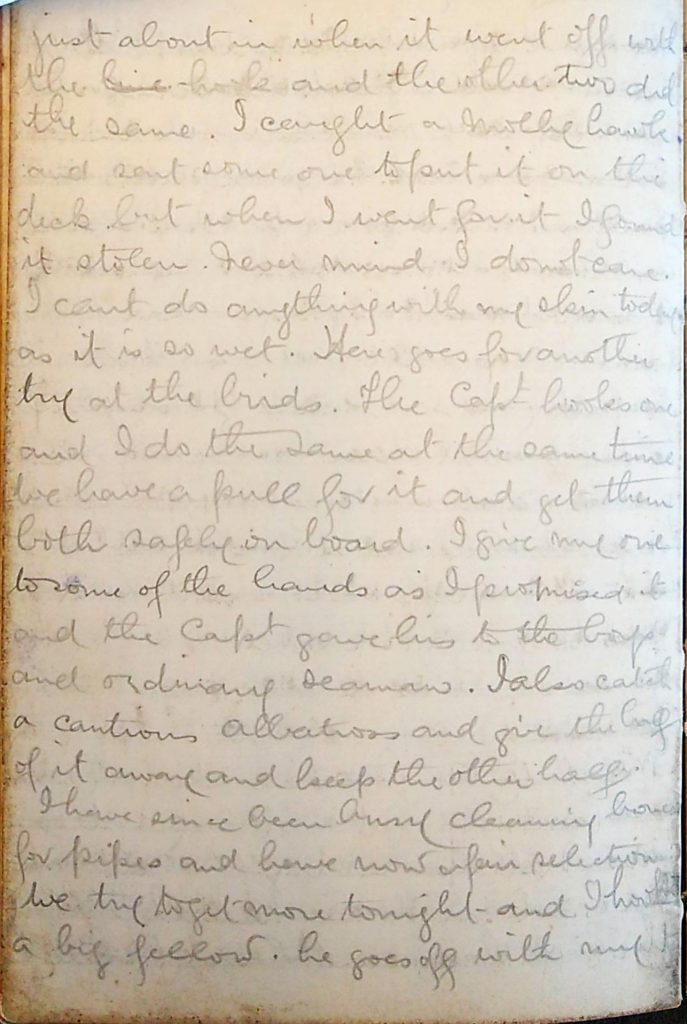

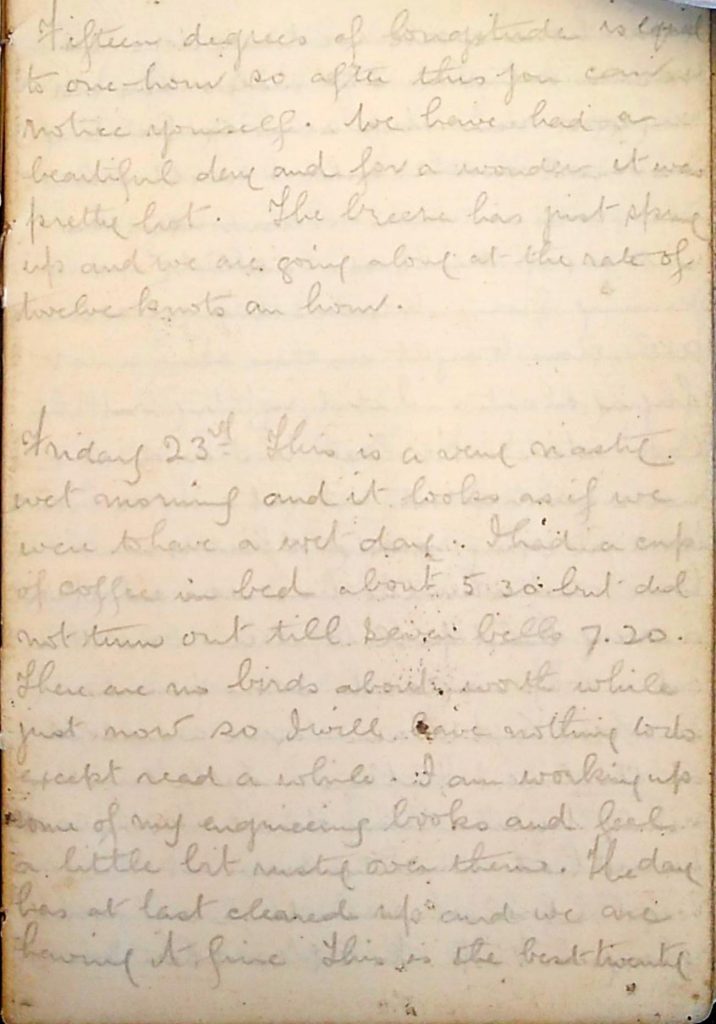

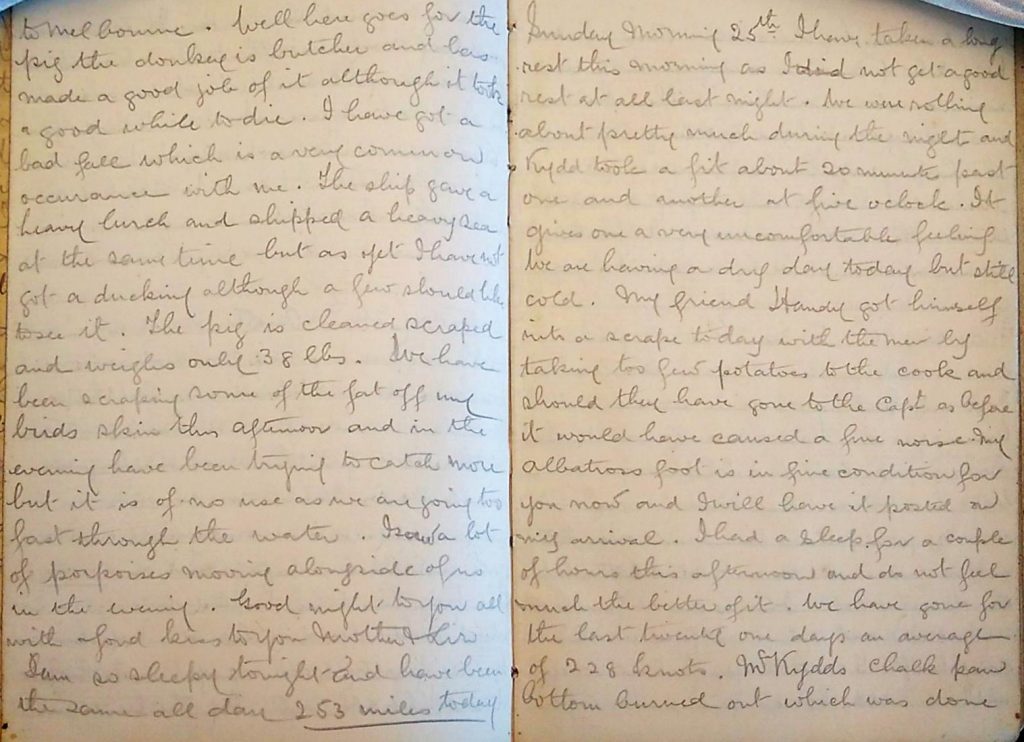

19th-25th January 1885

James reports that the 19th is a ‘very wet nasty morning’ and that he hunts for more birds. Several pages are then missing from the diary and we fall on what is presumably the last lines of the entry for the 22nd, ‘a beautiful day and for a wonder it was pretty hot’. The 23rd however is again a ‘very nasty wet morning’. With nothing to do and no birds around James reads his engineering books, giving us an idea of his occupation and perhaps the reason for his higher status onboard. The ship has ‘the best twenty-four hours work’ so far covering around 280 miles. Kerguelen Islands or the Desolation Islands are off to the north about 180 miles showing how close they now are to Antarctica. ‘If we should continue at this rate for the next 13 days we should be in Melbourne’. James tries to stay positive after he takes a fall, is kept up at night by the rolling of the ship and the continuing fits of Mr Kydd. ‘I have not heard any singing amongst the men this afternoon and I think that everyone must be like me out of sorts’.

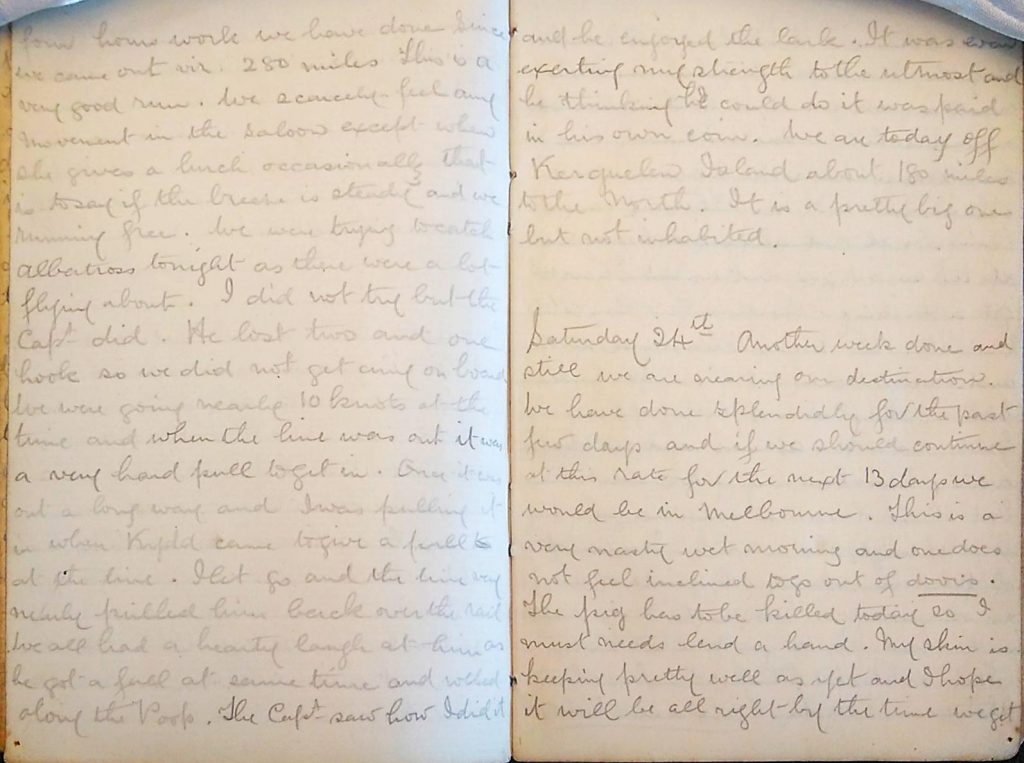

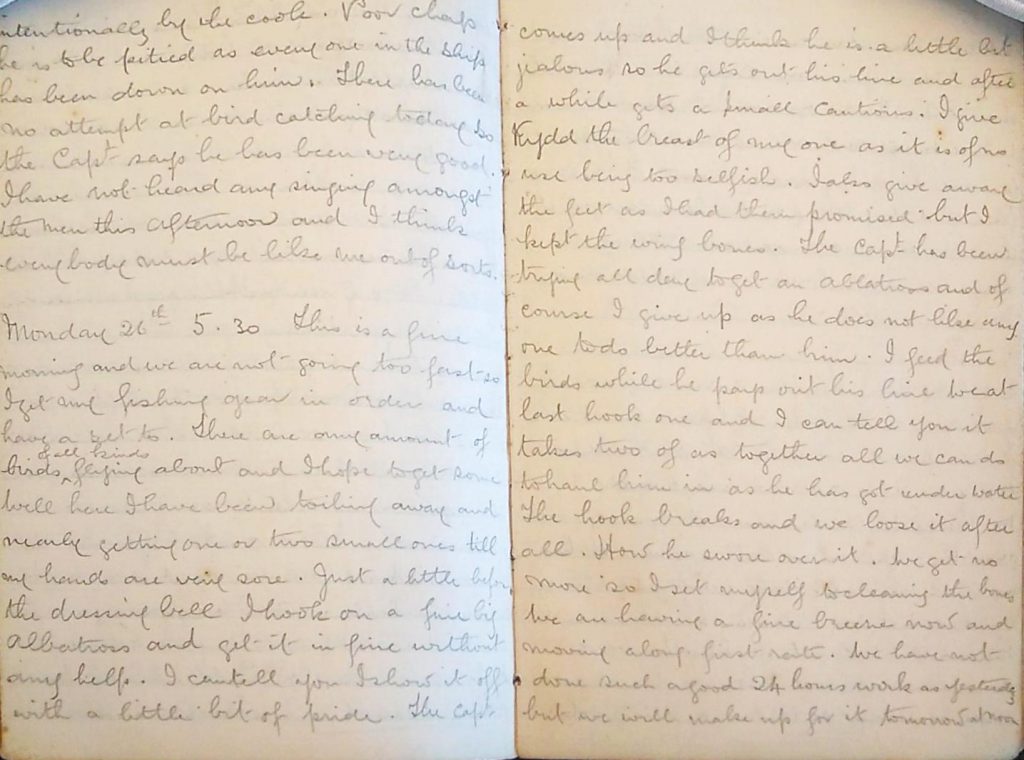

26th-28th January

‘The Captain is such a selfish man, but I can humour him fine’. The Captains meanspirited character is on show again as he and James try and catch more albatross. After catching one and giving Kydd the breast, ‘as it is of no use being selfish’, James reluctantly ‘gives up’ as the Captain ‘does not like anyone to do better than him’. Grand winds speed them along amidst wet and dirty weather, with both the Mate and Steward falling ill. Again, James attends to the sick and we gain a sense of his own character through this and his wish to ‘put vain notions’ into Handy Andy in order that he might become more independent. The weather turns stormy very quickly in the night, ‘the wind is shrieking through the ropes’, ‘I can’t go to bed somehow as I have tonight a sort of dread of Something’. Even the pitiless Captain, who James finds looking for ‘Dutch courage’ in whisky, gives the men ‘two tots of grog each’. The sea throws over the ship and a ‘sudden blast came on and through rain and blinding spray we can scarcely see the men’.

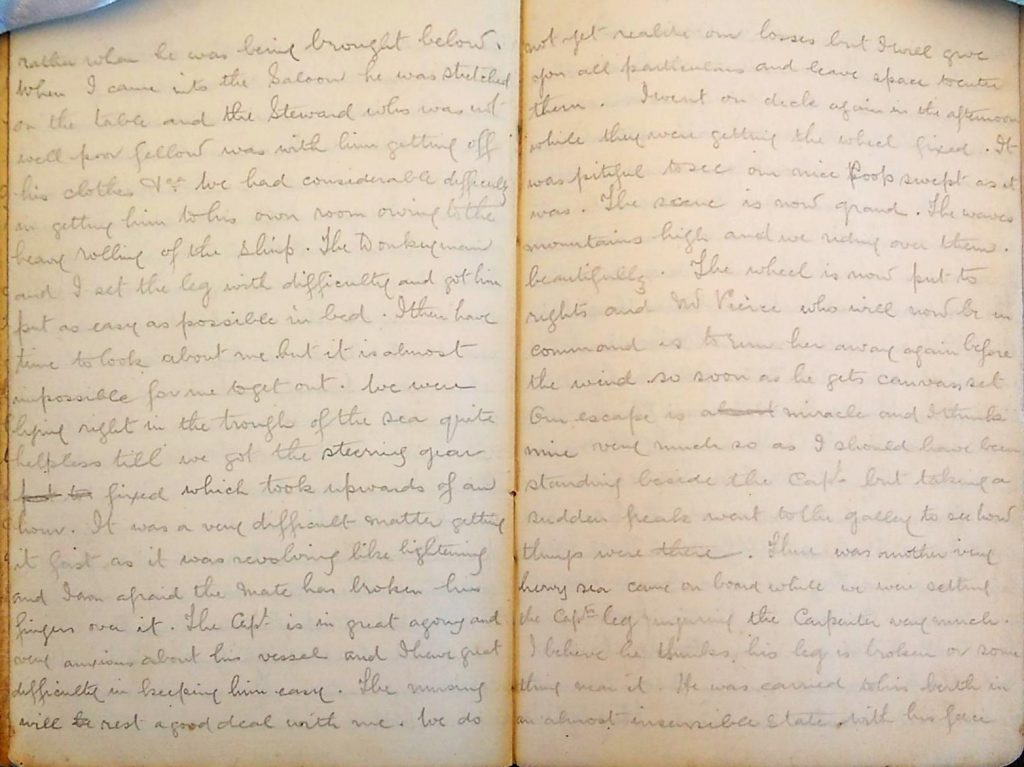

29th January 1885

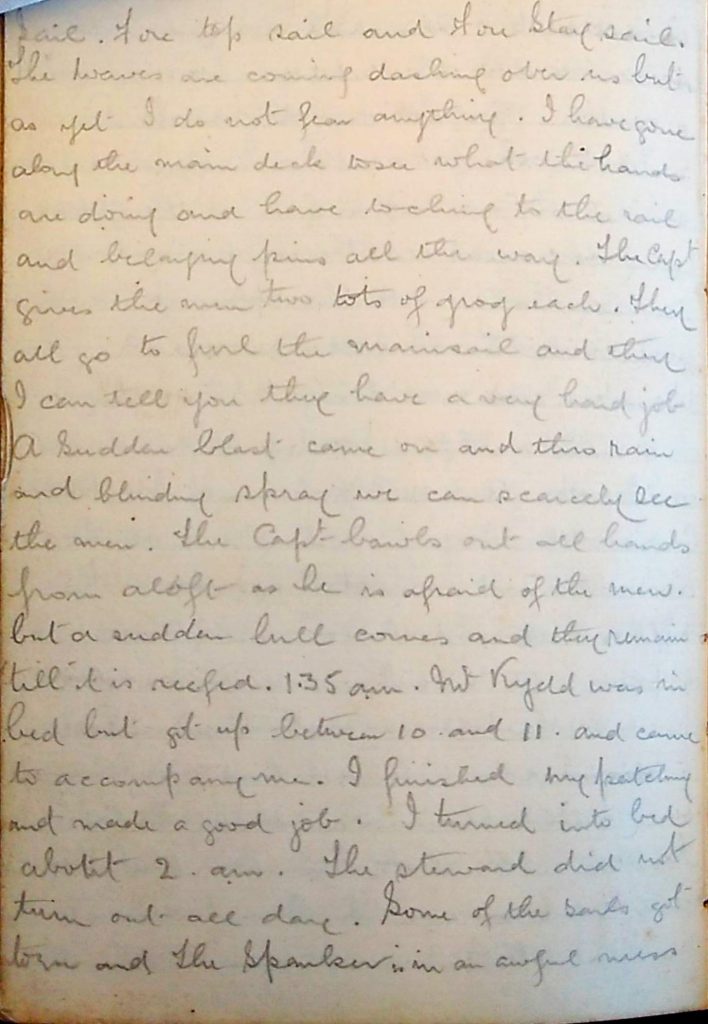

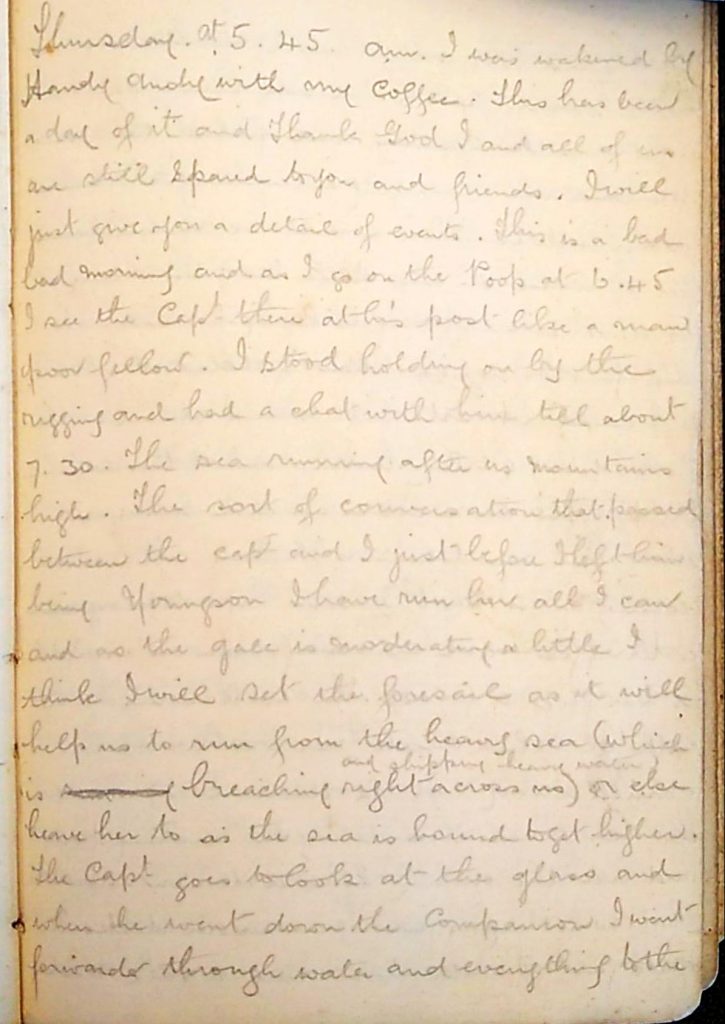

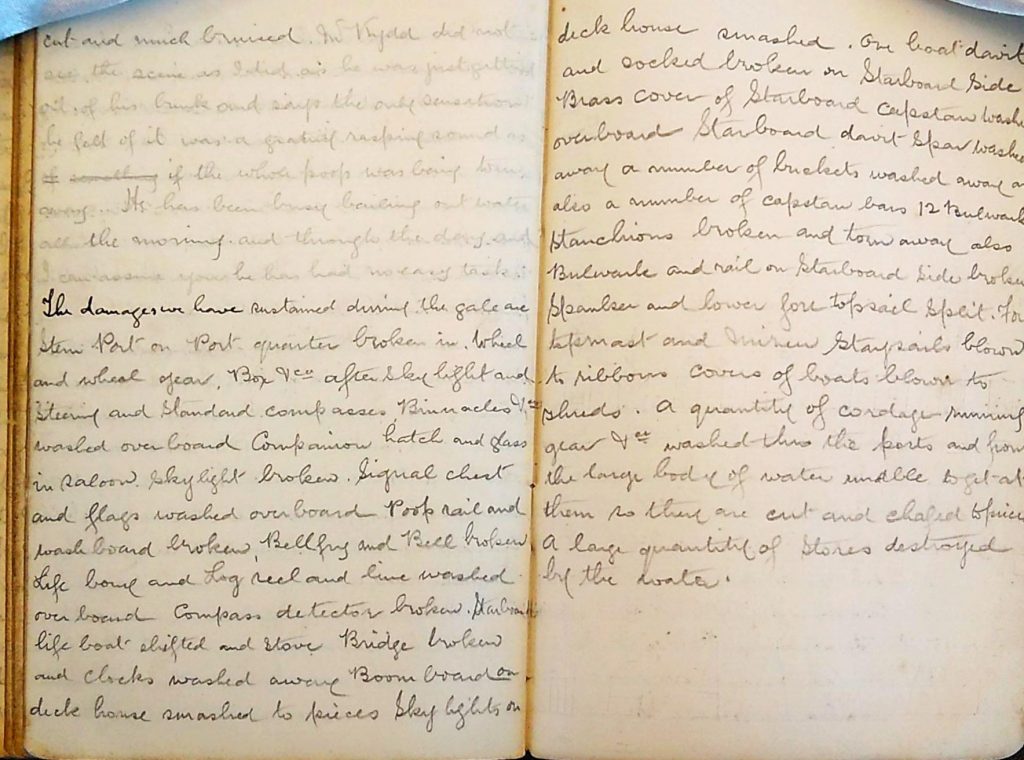

The final entry of the diary is quite fittingly also the longest and most riveting. James’ friend Handy Andy wakens him with coffee in the morning, but the mood very abruptly changes. James finds the Captain at his post at 6:45am ‘poor fellow’, the ‘sea running after us mountains high’. There is a sense of the ominous, a foreboding. James and the blanched cheeked cook look out from the galley ‘a terrific wave coming down upon us with as terrific a force… A very heavy sea broke right over the galley and filled the vessel fore and aft carrying everything movable along with it’. After more than two months onboard with James the threat of imminent peril is very emotive. Having come so far, the thought of the ship now failing seems a particularly cruel end. The risk anyone taking this passage voluntarily took compels us to place them in the world, to question their motives and try to appreciate their commitment in getting to Australia; what drove them to take such a risk? Were they running from something, did they have an unquenchable need for adventure, did they have perhaps no idea of the dangers they were exposing themselves to? ‘The sea comes thundering on, rushing past and over the galley like a demon. We note that something is wrong as our decks are quite full of water from rail to rail, and the men clinging to what they can lay hold of, the ship is broaching and shipping sea after sea… the expression of everyone’s face is fear’. To think if we only ever had the passenger lists, the names of the crew and the ship, the cargo. J R Youngson, Age 31, nothing more. ‘Ebb and Taylor have gone washed overboard with the wheel which is away, and the Captain got his leg broken.’ The Captain asks for James and they have great trouble getting him to his room amidst the heavy rolling of the ship. James helps nurse the Captain and thankfully the wheel is fixed and ‘the scene is now grand. The waves mountains high and we riding over them beautifully… Our escape is a miracle and I think mine very much so as I should have been standing beside the Captain, but taking a sudden freak went to the galley to see how things were there.’ The diary ends with a list of the damages sustained to the ship throughout the storm.

Afterword

Without the passenger lists of arrival it would have been impossible to tell if James or indeed the ship (as we had no vessel name) had made it to Melbourne. If the tale of the voyage had been a novel it would have been difficult not to invest in James’ story. Being a first-hand account, it may be argued that this investment is heightened still. It seems important to tell such stories for they inform how we engage with the past and give precious insight into historical experiences. Here lies one of the special prospects of visiting the archive. To sit and read James’ actual diary, in his own pencilled handwriting, is a wonderfully intimate experience and one we wished to share with you. We hope you enjoyed James’ story as much as we have and invite all feedback and comments as we prepare further Stories from the Archive to share with you soon.

Read more Stories From The Archive

References

[1] ‘Unassisted passenger lists’, Public Record Office Victoria<https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/explore-topic/passenger-records-and-immigration/unassisted-passenger-lists>[Accessed 25th August 2020]

[2] https://collections.slsa.sa.gov.au/resource/PRG+1373/10/7

[3] https://www.alamy.com/197-star-of-germany-ship-1872-slv-h99220-1229-image215043174.html

[4] https://www.google.com/search?q=clipper+route+map&safe=active&rlz.

[5] http://www.clydeships.co.uk/view.php?a1PageSize=75&ship_listPage=2532&a1Order=Sorter_types&a1Dir=ASC&a1Page=212&ref=55140&vessel=HELENSLEA