To be a fisherman, particularly during the herring fishing boom that took place in the late 19th century, was definitely not a job for the faint of heart. Not only did it take courage to stare down the ocean and take it on, but it also took great skill, both mentally and physically.

The hours were long and the season relatively short, with the herring season in Wick roughly spanning from July to mid September and the fishing primarily taking place at night. At night the herring came closer to the surface to feed and the nets were less visible.

The fisherman would head out at night searching for signs that the herring were shoaling. These signs might include whales surfacing or birds (such as gannets or gulls). If the night was particularly light and the sea calm it might even be possible to see a fine sheen of oil, indicating herring were to be found.

There was also the need to maintain equipment such as ropes, sails, and nets. Nets needed to be treated every 2 to 3 weeks to prevent rot.

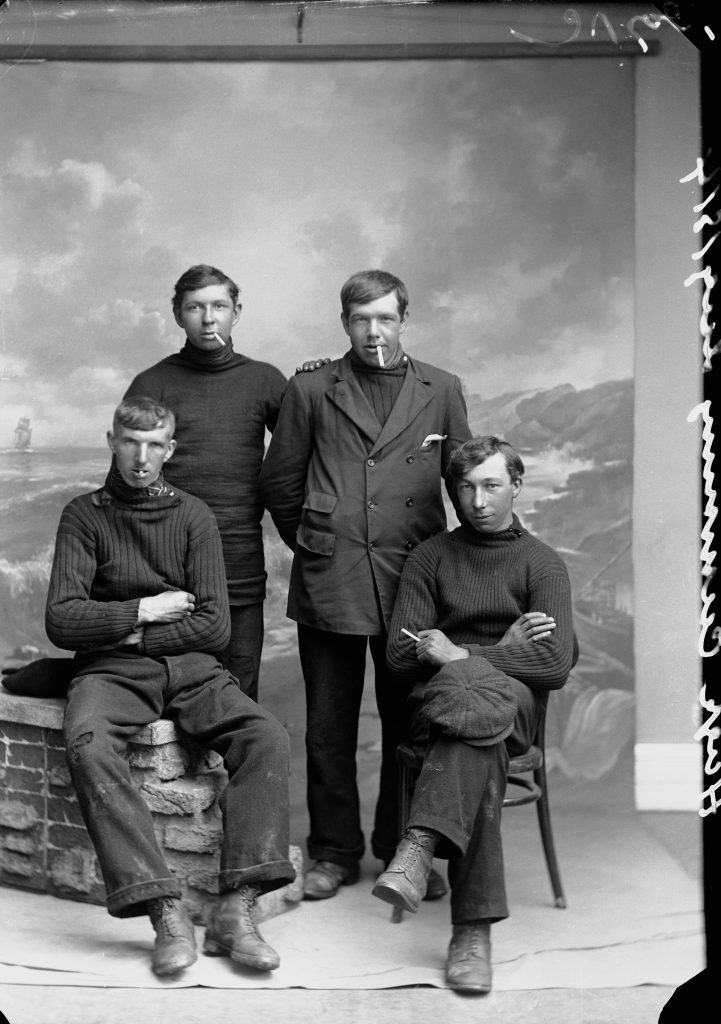

As a general rule a boat usually did not carry more than three hired men and they were usually all related to each other in some way or another. It is said that ‘they go to sea as boys, become men at eighteen and marry soon after’. They would generally marry ‘the daughters of fishers’ before 24 years of age. It was an equally hard life for the fisherwives.

Alcohol was a currency in the fishing business; business contracts were sealed with a drink and about a gallon of whisky a week was given to the crew (as cash was in short supply). Some figures estimate that as much as 500 gallons of whisky a day was drunk during the height of the herring season.

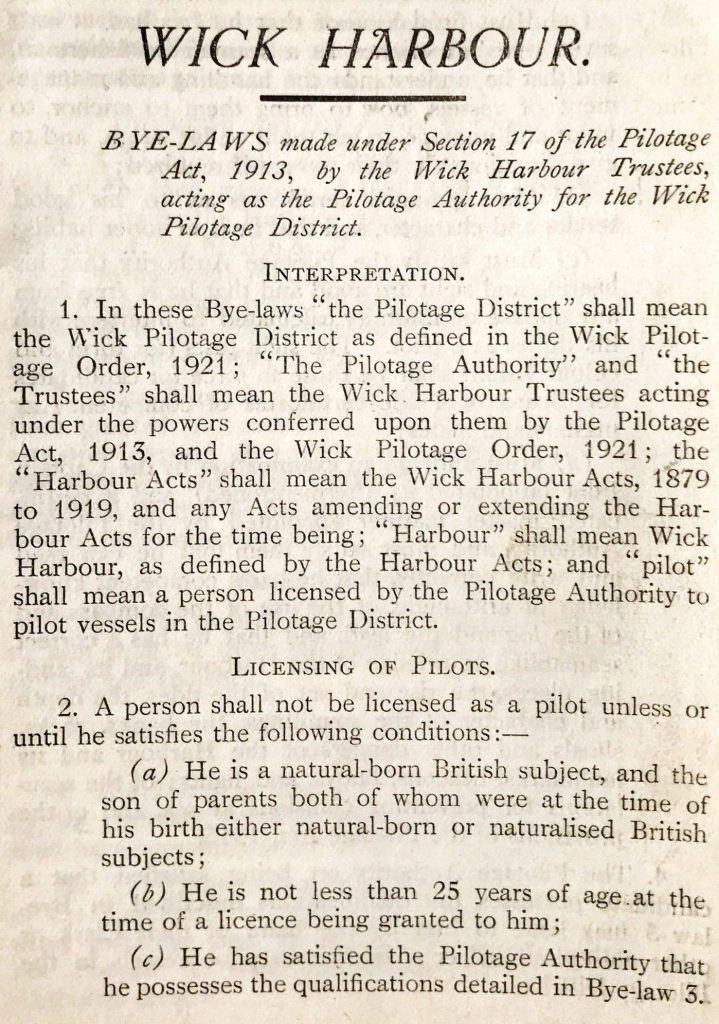

Pilot License – A “pilot” is a person who is licenced by the Pilotage Authority to pilot (or guide) vessels within a certain area or district (Ref: WHT/5/2/9/4)

Fisherman were easily identifiable by their mode of dress. Typically this would include such items as flannel undergarments, thick trousers, a hat and a thick jersey or gansey.

There is an old saying that a drowned man could sometimes be identified by his gansey, and with the constant threat of a watery demise it isn’t any wonder that fisherman were known to be superstitious. Some of these superstitions included taboo animals such as pigs, rabbits, hares and to a lesser extent swans and salmon.

It has been said that, when the fishing was poor, Caithness fisherman would make an effigy of a human, hanging it over the stern and burning it, in a procedure called ‘burning the witch.’

Another custom included painting pennies with a bright metallic paint and throwing it over board while saying, ‘if we canna catch ye, we’ll buy ye.’