Grace Wright is a PhD researcher working on women’s participation in nineteenth-century land agitation in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Born and raised in Skye, In Autumn/ Winter 2024 she was lucky enough to have the opportunity to undertake a three-month internship funded by the Scottish Graduate School for Arts & Humanities at her ‘home’ archive: Skye and Lochalsh Archive Centre. Below, she has reflected on her experiences.

I first became aware of archives through the COVID-19 lockdowns, using them for research online. The digitisation of records meant I could access documents from across the country at my leisure, even when travel was restricted and archives were closed. My introduction to the Skye and Lochalsh Archive, however, was a revelation. This came through ATLAS Arts’ School of Plural Futures programme, where the archivist, Catherine MacPhee, gave a talk about the archive and its hidden histories. Visiting and handling documents makes for a completely different way of connecting to the places and people woven through them. From there, the archive and its collections has shaped my research – a fact which made me all the more grateful for the opportunity to do an internship there, working on the treasure trove that is the Waternish Estate papers, SL/D266.

The Waternish Estate collection, is like a treasure trove, spanning three centuries from the early 1700s. The papers traverse the intricate task of managing an island estate, from inheritance dilemmas and financial management to the personal relationships within the MacDonald family, the heart of the collection. The main goal of my internship was cleaning, sorting, and cataloguing the papers. However, between new donations before my internship began and more since, the collection has grown arms and legs, and the project became a much larger one than was initially planned.

What struck me most was the undeniable human touch embedded in the collection. This personal connection made it impossible to remain impartial. Archives often carry biases, not only in what is preserved but also in how it is catalogued—a challenge I’ve grappled with as a women’s history researcher. The Skye and Lochalsh Archive Centre, however, offers something different, embracing the emotional essence that makes the stories within come alive.

Two smaller collections during my internship underscored this point. The first, a group of items donated from the Isle of Raasay. This came with a ‘weather log’ kept by Thomas Bunning, the butler of Raasay House during the infamous reign of George Rainy, who purchased the estate in 1846 having received money from the compensation given to former slave-owners following the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. His time as proprietor is characterised by attempts to limit the population of the estate, including subdividing crofts, clearing townships, and requiring tenants to seek permission to marry.While the weather logbook does occasionally reflect on the weather, its main subject is the comings and goings of the estate. On the 2 May 1853, it notes the first time the cuckoo was heard on the estate that year. In the next entry, the logbook records the arrival of seven letters from emigrants who had left for Australia the year before. This contrast – the seemingly banal with the forces of the Highland Clearances – hides a poetic irony. The cuckoo is known for being a ‘brood parasite’: laying its eggs in the nests of other birds so the cuckoo chick can usurp the care of the parents. Meanwhile, the island’s inhabitants have been evicted from the land of their forefathers to make way for expanding sheep farms.

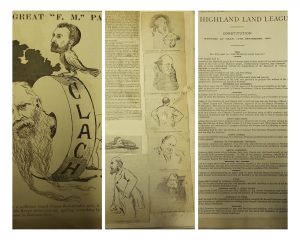

The second collection was from the family of Reverend James Reid, a Free Church minister based in Portree in the nineteenth century. He kept a scrapbook of mentions of land agitation in newspapers, spanning the Crofters’ War of the 1880s, including searing cartoons of the politicians of the day. This was bracketed by two heavy, silver candelabra, gifted to Anna Young Reid, the wife of Dugald MacLachlan, for their part in promoting the crofters’ cause. These added a tangibility to a story I had already been looking into for my own research: that of MacLachlan and his persecution at the hands of Sheriff William Ivory, the man responsible for the maintenance of law and order in Inverness-shire at the time. When Ivory’s attempts to have MacLachlan dismissed from his position as Sheriff-Clerk Depute in Portree were successful, crofters raised money to present MacLachlan with a gold watch and a purse of sovereigns.

The James Reid collection also contained several empty envelopes addressed to MacLachlan. What might have been discarded as rubbish has been kept by the family for a century and a half, and now fill a gap in MacLachlan’s biography. In his interview for the Napier Commission, a government board established to investigate the living conditions of crofters and cottars in the Highlands and Islands, he states that he has lived in Skye for most of his adult life, apart from several years spent abroad. Where, he does not specify, but the envelopes donated to the archives do. Spanning the early 1860s, they are addressed to him on two estates in St. Kitts: Dewar’s and Willetts. Both received compensation following the abolition of slave labour in the British colonies in 1834. However, exploitative forms of labour still drove the economy of St. Kitts during MacLachlan’s time there. In May 1861, the Dartmouth arrived in St. Kitts bearing indentured servants from India under the Indian indenture system which saw more than 1.6 million people transported to European colonies to ensure a steady supply of labour. A group of these indentured servants were sent to Dewar’s estate. This offers another thread in the story of Skye’s link to the British Empire as a source of opportunities for young men. It also, however, highlights a hypocrisy inherent to MacLachlan’s support of the crofting cause: he was calling for an end to oppression and displacement at home – highlighted in Bunnings’ logbook – having participated in and profited from it abroad.Beyond the individual collections, the archives themselves are more than the sum of their parts. The community memory it spans creates a sort of magic, woven through the coincidences and epiphanies which it hosts on a daily basis.

- A local historian appearing the afternoon it was suggested he would have the answer to my question.

- My mother opening a police logbook to find my great-great grandfather’s name on the first page she turned to – likely not for the reasons you’re imagining.

- Seeing my own hobbies reflected in the belongings of the MacDonald sisters, Catriona and Mairead, and getting the time to take a deep-dive into their lives.

These threads of belonging are the essence of what the archives does. Donations arrive in Co-op bags, cardboard boxes, and jacket pockets in answer to gaps in records we didn’t know existed. They are cleaned, listed, and numbered, sorted into boxes and onto shelves. From there, they build identity and culture, from collections spanning thousands of objects to envelopes emptied of their contents decades before. Following three distinct collections through this journey has been a privilege, seeing the impact they have on our understanding of ourselves. The archives are not just repositories of history; they are living, breathing reflections of the communities they represent.